The Battle of Nicopolis (Nikápoly) 1396

On September 28, 1396, the Battle of Nikapolis occurred, marking a significant moment in the European peoples’ campaign against the Turks. The goal of the alliance was to halt the Ottoman Empire’s expansion and remove the Turks from the Balkans. While the Thuróczy chronicle doesn’t specify the exact date of the battle, the author notes that it happened “around the feast of St. Michael the Archangel” over 627 years ago.

The situation before the battle

“If the sky were to fall on us, we would hold it up with our spears to prevent harm,” (it was how the western knights boasted before the battle according to the Thuróczy Chronicle).

627 years ago, on September 28, 1396, the Battle of Nicopolis was fought, one of the turning points in the campaign of the European nations against the Turks. It was a significant moment in the struggle of the peoples of Europe against the Turks. The aim of the alliance was to stop the expansion of the Ottoman Empire and to expel the Turks from the Balkans.

At the time, they thought they could have dealt a heavier blow to the young empire. Our short study seeks to portray the early anti-Turkish activities of the Hungarian King Sigismund (Zsiigmond) of Luxembourg and some of their Székely aspects. Read more about the Hungarian Székelys of Transylvania here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/who-were-the-szekelys/

The Thuróczy chronicle does not provide the precise date of the battle. The author only notes that it happened “around the feast of St. Michael the Archangel”. In our article, we do not focus on a specific day, but on the entire process. We observe that King Sigismund implemented a well-planned and thoughtful strategy, which justifies calling him a great ruler.

Military and diplomatic background

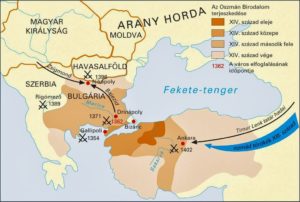

Due to the Battle of Rigómező (Battle of Kosovo) in 1389, the Kingdom of Serbia (Rácia) was no longer independent, making our country a neighbor of the Ottoman Empire. At the start of his reign, Sigismund of Luxemburg recognized the danger from the south.

Initially, he believed that strengthening the federal system with states inherited from Anjou would be the best course of action. His objective was to improve relations with Moldova, Wallachia, and Bosnia, while simultaneously leading campaigns in the Kingdom of Serbia for several years.

Turkish and Serbian attacks became regular in Temes, Krassó, and Szerémség counties. Perényi Miklós defeated many Turkish armies in Szörény between 1389 and 1392, and King Sigismund successfully besieged the castles of Čestin and Borač in northern Serbia.

The success of Hungarian campaigns is affirmed by Paolo Santini da Duccio in his work “De Machinis” through a map of the Balkans dating back to 1470. The map depicts Byzantium, Vidin, and Nicapolis with a flag with a cross from the year 1470. Before the occupation of Byzantium in 1453 and even as early as 1393, this representation depicts the state of three cities. The short inscriptions in Italian show that the royal armies marched at Orsova and the southern passes of the Carpathians, which indicates the campaign of the Hungarian king.

Sigismund of Luxemburg’s planned military movements are supported by documents he issued during the Southern Banates (Dukedoms), and other sources confirm his military activity. The young ruler diplomatically and firmly led both the Hungarian nobility and the Hungarian Székelys of Transylvania, as well as his allies, into war.

Szécsényi Frank, the Voivode of Transylvania, took part in the Serbian campaigns. His army certainly included Székelys whose military duties included recruiting, scouting, and guarding the passes, and they may also have been tasked with spying in the neighboring voivodeships.

We know from Nagyszeben’s later account books that the Saxons relied on skilled Székely archers to defend the city walls. The sentries in the snowy mountains also provided a fast courier service. In 1392, with the assistance of Bohemian, Silesian, and Austrian auxiliaries, and even with the help of English knights, Sigismund successfully negotiated with several rulers and advanced to Ždreló.

Sultan Bayezid chose not to face his enemies directly and concentrated his forces in 1393 against the Bulgarian states in the Balkans (Tirnovo Czardom, Vidin Czardom), which fell or came under full Ottoman control. These regions either surrendered or were conquered by the Ottomans. Now, the path towards the north was open for the Turks.

Prince ‘Mircea cel Batrin’ of Wallachia had already fought on the side of the Serbs against the Turks in the Battle of Kosovo, and now he had to defend his own country. On October 10, 1394, the Ottoman army attacked his small state. Mircea fled to Hungarian territory, and as a result, the Sultan replaced him with Vlad.

In that year, Voivode Stephen of Moldavia blockaded the Carpathian Straits and called his followers to war against the Kingdom of Hungary. Zsigmond countered the unrest in the principalities with two campaigns. At Kanizsai István’s command in 1394, the “powerful legions of the Székelys” penetrated through the line of the newly raised border zone and advanced to Szucsava with the incoming units of the royal army.

During the campaign, the Székelys of Kászon drew attention to themselves by asking for their own independent position of lieutenant and for the independence of Kászonszék. Although this was only fully accomplished during the reign of King Matthias, this remarkable act gave the initial impetus to the possibility of an independent administration and its separation from Csíkszék.

The Moldavian prince surrendered to Sigismund during the campaign, and the Kanizsai family was enriched with new donations for its loyalty. This comes as no surprise, as Kanizsai Miklós, who was not only a skilled diplomat but also played a crucial role in the military victory, had already talked over plans for a joint crusade with the Western rulers.

In 1395, the second counterattack of the Kingdom of Hungary was launched, in which the Transylvanian forces again participated in greater numbers. Mircea cel Batrin, who had been appointed Prince of Fogaras, marched into Wallachia with his Romanian troops to regain his dignity and throne.

The campaign was again led by Kanizsai István, Comes of the Székelys, who was seriously wounded in the fighting. They pushed the Turks back to the Danube and conquered Little Nikápoly / Nicopolis (Holovnik in Bulgarian, Turnu Măgurele in Romanian), opposite which stood the ancient city and castle of Nikápoly / Nicopolis with a strong Turkish garrison.

Sigismund’s campaign was abruptly terminated in May 1395, when the pregnant Queen Mary had an unfortunate riding accident, died on May 17, and was buried in Várad.

The Battle

As a result of the negotiations prepared by Kanizsai Miklós, and thanks to Sigismund’s authority, a large Western army gathered in Hungary in 1396 to crusade against the Turks. French, Burgundian, English, Polish, and German knights, as well as archers and crossbowmen, came to help.

Together with the Hungarian army, they crossed the Danube at Orsova and then systematically occupied the smaller fortresses on the right bank of the river on their way to Nikápoly. Another army, led by the new Transylvanian voivode Stiborici Stibor, came from the direction of Wallachia, reinforced by the army of the reinstated voivode Mircea, and arrived under the walls of Nikápoly.

The Székelys formed a wing of the army surrounding the city, along with the Transylvanian Hungarian troops. It was surely because of their reconnaissance and their fast, effective light cavalry fighting style that Sigismund considered it important to place them on the wings. They probably took their place alongside the troops of Voivode Mircea of Wallachia.

Nikápoly was strategically located on an ancient military route where the Olt River, which meanders from Transylvania, flows into the Danube less than 2 km away. The city’s importance was enhanced by the long-standing salt trade on the Olt and by the fact that it was once the center of the fallen Bulgarian state (the Tirnovo Tsardom). Its recapture would have been an inevitable step to break Turkish power in the Balkans. However, Sultan Bayezid gathered his army and set out to liberate the castle. For the first time, a large Janissary force of nearly 2,500 marched with his troops.

Taking advantage of the topography, the Sultan’s army took up positions in several stages in front of its own fortified camp. He placed the light, maneuverable cavalry in the front ranks, with the weaker infantry troops behind them. In the third line were the disciplined, trained Janissaries, capable of stopping the cavalry, who fortified their positions with sharpened stakes. The wings were lined with spahis of the Anatolian and Rumelian cavalry. Besides the Sultan’s cavalry, the Serbian heavy cavalry, a considerable reserve, was hiding in the hills.

We are not sure about the course of the battle, but we can reconstruct it from later sources. What is certain is that the army led by the Hungarian king was not unanimous on how to start the battle, because there was a serious disagreement in the council of the Christian allies.

The Franco-Burgundian leaders stuck to their own ideas and began their heavy cavalry charge before the royal armies had even developed. The Székelys and the cavalry of Wallachia were thus unable to prevail, even though their fighting style would have meant that their role would have been to disrupt the enemy’s lines and harass them with archers.

The Turks on light horses could not stop the attack of the knights, or they split up in front of them, so they advanced to the stakes set up by the janissaries. According to Thuróczy’s chronicle, the knights, having lost their momentum, dismounted and continued the battle. The Sipahies then attacked the Franco-Burgundian army.

In the bloody confusion, the horses ran toward the Hungarian army and camp, which may have caused even more alarm by making those in the rear believe that the attackers’ front lines had been destroyed. The Hungarian cavalry attack was not long in coming, however, and the Sipahis found themselves in a difficult position.

At the time, it might have seemed that the battle could end positively for the Christians. However, Sultan Bayezid I moved the vassal Serbian heavy cavalry from the cover of the hills, and the Hungarian cavalry was flanked by the Serbs, and the outcome of the battle was practically decided.

The sources then emphasize the headlong flight of the Christians, with Sigismund of Luxembourg barely escaping the scene. According to tradition and some sources, the king’s life was saved by Cserey Balázs, a Székely from Barót, who was able to return home by boat via Byzantium only after an adventurous journey accompanied by Kanizsai István and his Székely bodyguard.

As a result of the defeat, Sigismund abandoned offensive campaigns and began building a system of fortifications along the southern border; as a mature ruler, he introduced military reforms that ensured the long-term defense of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Source: Institute of Hungarian Research, Sashalmi-Fekete Tamás

Also, you can watch this video where further details can be learned about the battle:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v_0-Vc7uA4g

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all