Hungarian Men’s Attire: Mente, Dolman, and Boots

Originally, the term “dolama” referred to a long and loose garment with narrow sleeves and an opening in the front. Generally worn by Turks, it resembled a cassock in shape. In Hungary, now it is called “dolmány”. It became rather popular in the 16th century. In Sopron, it was called “dómán”, and in the Csallóköz region they called it “dokány”, in Szeged it was “dóka” while in Transylvania it was “domány”.

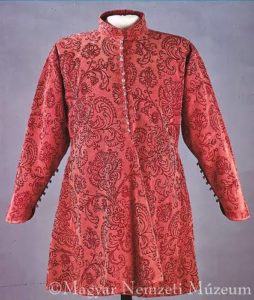

The so-called “mente” was a short coat, often it was lined with fur, and soldiers wore it over their shoulders. They were it over the Dolman. In the picture, you can see a mente:

The dolman of Eszterházy (1), around 1640; the “mente” of Prince Bethlen Gábor (2-3) from 1620; the dolman of Eszterházy Pál (4) from 1680 and the velvet dolman of Lord Bánffy (5) from Transylvania from the 1640s.

The Dolman entered Western culture via Hungary starting in the sixteenth and continuing into the nineteenth century when Hungarian Hussars developed it into an item of the formal military dress uniform. The jacket was cut tight and short and decorated with passementerie throughout. Under this was worn an embroidered shirt that was cut tightly to the waist and beneath which the shirt flared out into a skirt that sometimes reached nearly to the knee.

Pictures: Eszterházy Pál’s dolmány from 1680, is on display in the Museum of Applied Arts in Budapest:

A decorated saber or sword hung from a barrel sash around the waist. The elaborate style of the dress came to reflect cultural values concerning romantic military patriotism. A second garment called a pelisse was frequently worn over it: a similar coat but with fur trimming, most often worn slung over the left shoulder with the sleeves (if any) hanging loose.

Boots

Hungarian boots from the end of the 17th century, displayed in the Museum of Applied Arts, Budapest.

In the 16th century, the color of the boots was red or yellow, and black (or blackened) ones were worn only at funerals. They were also quite valuable: I heard that a village in the Ottoman-occupied lands of Hungary always sent a pair of boots as a tax to its Hungarian landlord, who had fled to distant lands from the new conquerors.

It has always fascinated me how the Hungarian peasants deep in the Ottoman lands paid (or tried to pay) taxes to their often long-forgotten landlord who had fled to the north. Sometimes the landlords sent their tax collectors to their old estates, which were hundreds of miles inside the territory controlled by the Turks. Nevertheless, they were able to collect (some) taxes despite the difficulties.

The peasants paid willingly enough, it was their last link to the hope that one day they would be reunited with their lords and land.

At the same time, the landlords never gave up their claims to their old lands and paid close attention to their properties, even though the Ottoman Sipahi landlord had long considered the village to be his domain.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!