Kinizsi Pál, general of King Matthias

Kinizsi Pál (1432-1494), also known as Paulus de Kenezy (in Latin), Paul Cneazul, or Pavel Chinezu (in Romanian), was a general in the Hungarian army under King Matthias Corvinus. Not only Hungarians but also Serbs and Romanians claim him as their hero. But as I always say, in those days, love of country and loyalty to the monarch, together with religion, was more important than language. Note that in my articles I use the oriental order of Hungarian names, with the surname coming first.

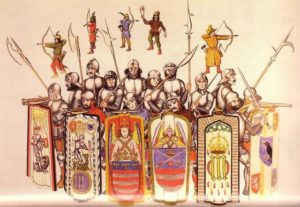

The medieval Hungarian kingdom flourished during the reign of King Matthias Corvinus (1458-90). The young king was able to make his rule more effective by creating a new high nobility from the talented sons of the lower and middle nobility, who were loyal to him because they were dependent on his person. Kinizsi was one of them.

Kinizsi was Count of Temes County (in the historic region of Bánát, now part of Serbia and Romania) and Captain-General of the Lower Parts from 1484. He served under the command of Magyar Balázs, the general of Matthias’s standing army. At first, he was Magyar’s vice-general, then he became the general of the famous Black Army. Perhaps his most notable deed was the victory over the Ottomans in the Battle of Breadfield (Kenyérmező) in October 1479. He is one of the few generals in the world who never lost a single battle or personal encounter.

According to some Serbian historians, he was of Serbian origin and possibly a descendant of Vuk Branković, although this could not be proven. According to Hungarian and Romanian folk tales, the king was hunting in the Bakony forest near the mill where he worked and asked for a drink; Kinizsi, to show his strength, served the cup on a millstone. Impressed, the king took him into his service, where Kinizsi’s strength, skill, and loyalty earned him rapid promotion. However, we know that this is just a legend because he came from a noble family.

He is said to have wielded two swords in battle and, after the Battle of Kenyérmező (also known as Breadfield), to have danced a victory dance with a captured or dead Turk under each arm and a third held by the hair or belt in his teeth.

The first time his name was mentioned was in 1464, in a Latin document, where it was stated that Egrenius (His Excellency) Paulus de Kenezy was granted property in the county of Abaúj. Later, in 1510, his name also appeared in the form of “Paulo de Kynys Comiti Themesiensi et Generali Capetaneo partium Regni nostrum inferiorum”. His name appeared in 1468 in the army led by General Magyar Balázs in Moravia as his vice-general.

Some historians say that he came from a poor noble family in Bihar County, but we can find families with the name “Kinizsi” in Székely Land in Transylvania and in Abaúj-Torna County (see the village of Nagykinizs). We know that his father had fought against the Turks in the army of Hunyadi János, so he could not have been just a miller’s son. He was most likely the son of Hungarian Székely warriors. Here is more about the Székelys:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/who-were-the-szekelys/

Kinizsi was the Comes of Máramaros County from 1467 to 1472. He received the castle of Vázsony from King Matthias Corvinus in 1472 in return for his faithful service in the Polish wars, but more Polish and Bohemian wars were to come, so he was in line for further promotion.

In the autumn of 1474, King Ulászló (Władysław) of Bohemia (1471-1516) and King IV. Kázmér (Kazimierz) of Poland (1444-92) joined forces and attacked King Matthew at the instigation of Matthew’s greatest enemy, Emperor Frederick III (1452-93). Matthias held Silesia at the time and the two kings attacked him from two sides. Kinizsi was there and he distinguished himself in the war at Boroszló (Wroclaw) in 1474. The hussars of Kinizsi and Szapolyai István successfully cut the enemy’s logistical lines, which ultimately brought success to the king. You can read more about this particular war of King Matthias, where he defeated an army nine times larger than his own:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/king-matthias-at-boroszlo-wroclaw-breslau/

We know that he led his own army into Austria in 1477, where he besieged a castle on behalf of his king. At home, Kinizsi enlarged the castle of Vázsony and added a Pauline monastery in 1478. He was not only a daring military leader with a certain savagery, but also a generous landlord. The surroundings of (Nagy)Vázsony developed rapidly during his time.

Two years later, he received Somló Castle as a wedding gift from the king, as it was the year he married Lady Magyar Benigna. She was the daughter of Magyar Balázs, the famous general of King Matthias Corvinus. When Baron Újlaki Miklós died in 1477, King Matthias had to reorganize the defense system of the southern Borderland. As a result, the Dukedom of Macsó no longer controlled the southern counties of Hungary.

The king took over the function of the governor of Temes County and the chief captain of the Lower Lands. Kinizsi was appointed as the head of Temesvár Castle and as the military leader of Lower Hungary, he was in charge of the southern defense of the kingdom. More precisely, he was responsible for the eastern part of the double line of border castles between Croatia and Transylvania.

The Turks attacked Hungary from two directions in 1479: they attacked the Trans-Danubian region and Transylvania at the same time. In the autumn, Kinizsi set off to help the Transylvanian voivode, Báthori István. He arrived in time to defeat the army of Bey Isa and the Wallachian (Romanian) voivode Basarab IV at Kenyérmező (Breadfield) on 13 October. You can read more about this famous battle at Kenyérmező:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/1372-1490/the-battle-of-breadfield-kenyermezo-1479/

In response to the Turkish attacks, the Hungarians launched several punishing campaigns against the Ottomans in 1479-80. The king personally led his troops into Bosnia, while Báthori and Voivode Stefan III of Moldavia (1457-1506) attacked Wallachia. Kinizsi was sent to Serbia. Kinizsi led several campaigns against the Ottomans in Serbia because the king wanted to place the theatre of war on the enemy’s land. Kinizsi was supported by the Serbian despot Brankovics Vuk. At the same time, many Serbs were seeking refuge in Hungary, so Kinizsi settled them in the Hungarian kingdom, where the local Hungarian population had been wiped out by the Ottoman invaders. He obliged the new Serbian settlers to fight in his army in exchange for the land.

In 1482, Kinizsi also defeated the Ottomans at Szendrő Castle. During this campaign, he led an army of 30,000 men as far as Krusevác. Sultan Bajazid and King Matthias made peace in 1483 for ten years, but the so-called ‘small war’ never ended. It was Kinizsi’s job to beat back the Ottoman raids on the borderlands.

After the death of King Matthias in 1490, it was mainly Kinizsi’s deeds that drove the Austrian army, which was about to attack, out of the kingdom. He then decided to support the new king, who had been Matthias’s enemy, King Vladislav (Ulászló) II. This forced Kinizsi to turn against Matthias’s illegitimate son and designated successor, Prince Corvin János. Kinizsi and Bátori may not have been in an easy situation when they had to fight and defeat the army of Prince Corvin János at Csontmező (Bone Field) in Tolna County. Unfortunately, the once-famous Black Army had become a band of brigands after being disbanded for lack of pay. Kinizsi destroyed the mercenary Black Army of his former king at the Száva River in 1492. The soldiers of the Black Army who refused to join their new master’s army were executed by starvation in Kövesd Castle.

After this, Kinizsi fought a few more battles against the Turks, for example, he saved Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade) when its defenders wanted to sell it to the enemy in 1494. He intervened and had the traitors cruelly executed. King Ulászló appointed him chief judge of Hungary that year. He then invaded Serbia and Bulgaria but was crippled by a stroke. Despite his illness, he tied himself to his horse and commanded his soldiers from the saddle. He died shortly afterwards during the siege of Szendrő Castle on 24 November (before 26 November) 1494. He was buried in Nagyvázsony, but his tomb was destroyed in 1708. Fortunately, a few items from his tomb were later found and we can now see his helmet, armor, and double-edged broadsword in the Hungarian National Museum.

The Festetics Codex

The most ornate Hungarian manuscript from the Middle Ages is “The Festetics Codex.” It is a Hungarian-language prayer book compiled for Kinizsi Pál’s wife, Magyar Benigna, in the Pauline Monastery of Nagyvázsony. The monastery was founded by Kinizsi in 1483 and its survival was ensured by rich donations. As a token of their gratitude, the monks probably gave the founder’s wife a representative parchment codex with the Kinizsi family coat of arms on one side and the Kinizsi and Magyar coats of arms on the other.

The main text of the manuscript was copied in one hand. Its date of origin can be deduced from the ‘Prayer for the Sickness of my Lord Pál’: Kinizsi died on 20 November 1494, but he had been seriously ill for two years, as the prayer for his recovery indicates, so the manuscript must have been written between 1492 and 1494.

The volume is one of the most beautifully presented language memories we have. The decoration reflects the influence of the Buda book-painting workshop, established under King Matthias, which employed Italian masters. The second page of the manuscript, which contains numerous initials and page proofs, shows the Virgin Mary as a sun-dressed woman in a rectangle above a crescent moon, next to the first seven lines of text, with a halo and the child Jesus in her hands. The neat appearance is enhanced by the neat typeface and the particularly careful and beautiful lettering.

Our early language record in this book relates to a type of prayer book, the lay Hora book, the composition of which may have been influenced by the needs of the patron. Its most important component, the Officium parvum Beatae Mariae Virginis, is the largest in the Festetics Codex (pp. 1-140, 183-362). The text contains 31 psalms, none of which is translated in the same way as any of the psalm translations found in the linguistic memorial codices.

The beginning of the Gospel of John (1:1-14), one of the most common components of the Horary, is also found in the Prayer Book; it was probably copied sometime later at the end of the manuscript on the originally blank but outlined pages (pp. 414-416). Another important element of the Horary, the seven penitential psalms, is also a popular chapter in the Hungarian prayer books that survive from the Middle Ages. It is noteworthy that in the Codex Magyar Benigna, the Pauline scribe did not copy the biblical texts, but Petrarch’s translation of the Seven Penitential Psalms (pp. 364-405). The text, whose content is independent of the biblical penitential psalms, appears here for the first time in a Hungarian translation and is not found in any other of our linguistic commemorative codices. The Latin original has been wisely and faithfully translated into Hungarian by an unknown translator.

The Pauline monks of Nagyvázsony prepared another prayer book for Magyar Benigna: the Czech Codex (MTA Library, Manuscript Archives, K 42) was copied by Brother M. in 1513. Both manuscripts are small, which can be explained by their purpose: as they were intended for the daily private devotions of their owners, it was important that they could be easily carried. The two books testify to Benigna Magyar’s ability to read Hungarian.

Nothing is known for certain about the fate of the Festetics Codex and its subsequent travels. Sometime at the end of the 18th century it was transferred to the Festetics Library in Keszthely and in 1947 to the National Széchényi Library. It was named after the Festetics family.

Source (Festetics Codex): http://nyelvemlekek.oszk.hu/

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!