Székesfehérvár

The city and castle of Székesfehérvár are located in the middle of Hungary. Székesfehérvár was initially just Fehérvár, it used to be the kingdom’s medieval capital, Alba Regia. It was one of the most important cities in Hungary. In the Székesfehérvár Basilica, one of the largest basilicas in medieval Europe, where the Diets were held and the Crown jewels kept, thirty-seven kings and thirty-nine queens were crowned and fifteen rulers were buried. The Ottomans and the Imperial mercenaries alike, unfortunately, destroyed and mixed the skeletons when robbing their tombs.

The city got its name from “the white castle of the royal seat”. Similar names were Nándorfehérvár aka Belgrade in Serbia or Gyulafehérvár aka Alba Iulia in Transylvania. Both used to get their names from Hungarian ranks like “nándor-nádor=palatine” or “Gyula”=military leader. “Gyula” was the keeper of Transylvania at the time of the home-taking in the 9th century, later this rank became the Voivode of Transylvania.

The town was founded in 972 by High Prince Géza, father of King István. Géza had a small fort built in the city, too. King István I granted proper town rights to the settlement, surrounded the town with a plank wall, had a provosty and a school built, and under his rule, the construction of the Basilica began (it was built between 1003 and 1038). The settlement had about 3,500 inhabitants at this time and it was the royal seat for hundreds of years. Forty-three kings were crowned in Székesfehérvár.

King András II issued the Golden Bull here in 1222. The Bull included the rights of nobles and the duties of the king, and the Constitution of Hungary was based on it until 1848. It is often compared to England’s Magna Carta.

During the Mongolian Invasion of Hungary (1241–1242), the invaders could not get close to the castle because the Mongolian warriors could not get through the surrounding marshes which were flooded by melting snow. In the 13th–15th centuries, the town prospered, and several palaces were built. In the 14th century, Székesfehérvár was surrounded by city walls. The Cathedral burned down in 1327 but it was soon restored.

After the death of King Matthias (1490), the Holy Roman Empire’s army of 20,000 men, led by Emperor Maximilian invaded Hungary. They advanced in the heart of Hungary and managed to capture the city of Székesfehérvár, which they sacked, and plundered the tomb of King Matthias, too. However, the Landsknechts were still unsatisfied with the booty and refused to set out to take Buda. Maximilian returned to the Empire in late December and the Hungarian troops liberated Székesfehérvár in the next year, led by Kinizsi Pál.

The fall of Esztergom in 1543

The city remained under Ottoman occupation for 145 years, until 1688, except for a short period in 1601 when it was re-occupied by Prince Mercoeur. However, Count Salm tried to take it back in 1566, just like Nádasdy and Schwarzenberg attempted it in 1598 but these were in vain.

The siege of 1601 took place during the 15-Year War and at the final attack, 4,000 Turkish soldiers died at the breach in a hard fight along with 1,000 Christian attackers. The Ottomans were fighting in the city from house to house and their heroism was worth recording. The brave Sanjak Bey of the city took himself with his 120 soldiers into a tower and fought to the end. He and his family were captured and the Christian prince took care that they could not be harmed. Prince Mercour gave them his own tent.

When the fight was almost over, Colonel Giovanni Marco Isolano who later became the town’s captain, said that “the Turks fled to the marshland around the castle who had to be rounded up there. The gunpowder was stored in the church which exploded after the end of the fight and the houses have burned out so much that only the walls of the unfortunate city were standing.”

Indeed, after the taking of the city, the winners visited the ancient cathedral to give thanks to God and the explosion happened right after they had left the building, killing “only” a dozen men. Gossip said that all the treasures were blown up which had been hidden there at the siege of 1543 by the Hungarians. It was recorded that the western mercenaries couldn’t find much booty in the torched town so they were so much angered that they attacked and plundered each other after the siege. The prince sent 1,500 Turkish captives to Győr city.

However, the Ottomans took the city back the next year from Colonel Marco because the German mercenaries surrendered the fort. The Turks have destroyed the remains of the city, demolished the royal palace, and repeatedly pillaged the graves of kings in the cathedral. The stones of the huge Cathedral were used to repair the walls and for other constructions in the city. Now, the bones of Hungarian kings are hopelessly mixed up with the sadness of researchers.

The Turks named the city Belgrade (“white city”, from Serbian “Beograd”) and built mosques. In the 16th–17th centuries, it looked like a Muslim city. Most of the original population fled. It was a Sanjak center in Budin Province as “İstolni Belgrad” during Ottoman rule. You can read more about the 15-Year-War on my page, I am sharing a long series about the events of this war:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/chronologie/the-fifteen-year-war-series-1591-1606/

The retaking of Fehérvár in 1688

During the war of reconquest against the Turks, Fehérvár was not on the main line of attack of the imperial armies. The troops of Charles of Lorraine moved along the Danube, while the rest of the army moved along the major rivers (Tisza, Maros, Dráva, Száva). Thus, Székesfehérvár remained in Turkish hands even after the fall of Buda (1686). During the siege, Charles of Lorraine sent Colonel Pálffy János with 1,000 cavalry to keep an eye on Fehérvár.

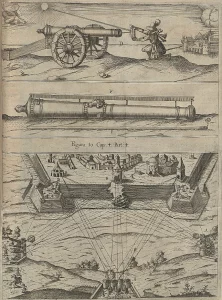

The Imperial troops were already along the Dráva and even beyond it when the Imperial War Council ordered the blockade of Fehérvár. On July 22, 1687, Esterházy János, the vice-captain of Győr, arrived in Kádárta, from where he sent raiding horsemen to Fehérvár. A few days later, Zichy István arrived with troops from Komárom, Esztergom, and Tata. He was the first to call for the recapture of Csókakő, for which he asked the commander of the Buda castle to send a monk whom the Hungarians called Tüzes (“fiery”) Gábor or Father Gabriel, who had used his skills to great effect during the siege of Buda, as he was very skilled with explosives. He was Italian by birth, and his name was Gabrieli Ráfáel.

The monk arrived at Csókakő Castle on October 15, and the next night he had the cannons set up, and the castle surrendered with the explosion of five bombs on the afternoon of October 17. On October 20, Tüzes Gábor was sent to the Zichy Palace and his bombs forced the Turkish garrison to surrender in two days. The retreating troops were escorted to Buda, where they were loaded onto ships and transported to the Ottoman Empire.

In Csókakő 200 guards were left under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Bizterczky, while in Palota 700 soldiers were left on guard. With the occupation of the two forts and Csíkvár, Fehérvár was cut off from its surroundings. As food supplies became increasingly difficult to come by in the fortress, more and more people tried to escape through the marshes. However, the allied horsemen hunted them down and put them to the sword without mercy. In January 1688, the pasha of Fehérvár allowed those who wished to leave the fortress to do so. At his request, the commander of Buda, General Beck, and the captain of the castle of Veszprém, Babócsay Ferenc, forbade the warriors of Simontornya Castle to kill the fleeing Turks.

Nevertheless, the situation of the Turkish defenders continued to deteriorate. The patrolling cavalrymen regularly picked up the messages of distress, and this gave them an idea of the increasingly desperate situation of the defenders. But they persisted, and this became a burden even for the Viennese command. In February 1688, Colonel Riccardi was sent to the scene to negotiate with the Turkish commander. However, Ahmed Pasha, the Agha of the Janissaries, and Zagargi Pasha refused to negotiate any surrender, and the imperials tightened the ring around the city. Supplies could not arrive (until then the Hungarian commander in Zsámbék, perhaps a renegade, had occasionally sent 1-2 wagons of supplies) and the War Council sent another 1000 infantry, 800 horsemen, 50 hussars, and 100 Hajdú soldiers. As a result of the restrictions, the number of people fleeing the city increased. Some groups of the garrison also started to riot.

Batthyány ÁdámOn hearing this, Riccardi, Bizterczky, and Esterházy again called on the Pasha to surrender, but the officers who appeared in front of the walls were met with gunfire. For this purpose they sent a more serious military force, the command was given to Count Batthyány Ádám II, the chief captain of the Transdanubian district and the Borderland opposite Kanizsa, and under him the 3000-strong army of Esterházy, Zichy, and Colonel Giovanni Ariezaga, the captain of Lipótvár was assigned.

They also brought artillery. On April 29, the Allies advanced on the siege, the Hungarians attacking from the northern suburb called Buda and the Germans from the northeast, from the direction of Keresztes. The defenders fired at the besiegers. Batthyány also ordered a strong force to the southern gate called Csíkvár to prevent a possible escape. A desperate Turlisk attempt to make a sally was made on May 6, but it failed and Ariezaga moved closer to the walls. Although this brought them within range, they could no longer be fired upon from the castle.

The next day, Batthyány wrote a letter to the commander asking for a quick surrender in order to avoid the destruction of the population. The Turks replied immediately, and the next day three envoys were sent to the camp. They were received by Batthyány, Esterházy and Ariezaga, and the terms of surrender were discussed. The commanders of the castle objected that the Muslim Turks, who had been Christians, could not keep their faith, but in the end, more and more of them urged acceptance. On May 9, the Pasha and his officers signed and sealed the document of surrender. Most of the points were the same as in the treaty signed by the castle of Eger, which had opened its gates a few months earlier.

by Jefferys, Charles W.

The equipment and military equipment in the castle were to be surrendered, the members of the guard and their families were to be transported by ship to the border of the Empire, and the Turks were to release the Christian prisoners. At the same time, however, about 50 children under the age of 18, born to a Christian mother and a Turkish father, were not allowed to go with them and were taken by the Jesuits.

The defenders sent envoys to Vienna to get the treaty accepted by the Emperor. In the meantime, friendly relations between the opposing sides began, and the Turks went to the camp to buy food. Some took advantage of this to plunder, and Ariezaga had the leaders of the plotting group arrested. On 14 May the Emperor signed the capitulation, and the Turkish envoys returned on 18 May. The next day, the guards and the population withdrew, while Hungarian and German soldiers occupied the city. The Turks left for Adony on the 20th, where ships were waiting for them. On that day, Bishop Szécsényi Pál of Veszprém celebrated a service of thanksgiving in the market square.

During the War of Independence of Prince Rákóczi Ferenc, the town sided with the Habsburgs. However, it was taken in 1705 by General Nádasdy Ferenc who was in charge of Rákóczi’s Trans-Danubian army. He started to build a new fort but it was pulled down at the end of the 18th century.

Today, not much can be seen from the old castle. The “ruin-park” at the previous place of the Basilica is the place where the mixed skeletons of the Hungarian kings are kept in a special chamber under the ground. Although the plundering soldiers of the past had done their best, the shame for the confused bones is mostly on the people who were responsible for them during the socialist period. If you visit the town, check out the Saint István Museum and Saint Anna Chapel by all means. Also, there is a modern castle in Székesfehérvár, it is the so-called Bory castle but it was built only in the 20th century.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

[wpedon id=”9140″]

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Here are a few more pictures of Székesfehérvár and the city’s remaining walls: