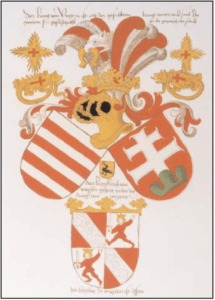

King Zsigmond / Sigismund (1368-1437) of Hungary

More exactly, Luxemburgi Zsigmond aka Sigismund of Luxembourg was also the king of Croatia, Bohemia, and Germany and became the Holy Roman Emperor as well. He was the most renowned ruler of his time in Europe, so I’m going to write about him a little longer.

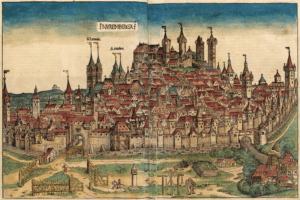

Born in Nuremberg on February 14, 1369, Zsigmond was always a great supporter of his hometown. However, as King Zsigmond of Hungary, he established the center of his empire in Buda, which he developed into a royal residence of European renown.

He organized the last all-European crusade in 1396, put an end to the Great Western Schism in 1417, and began the fight against Hussitism. The peasant revolt led by Budai Nagy Antal broke out at the very end of his reign. The reign of King Zsigmond of Hungary was not without its struggles, political intrigues, and events: it is no coincidence that the last ruler of the House of Luxembourg is considered one of the most important figures of late medieval Europe.

With the death of King Louis the Great, the last male heir of the Hungarian House of Anjou died, leaving the throne to the monarch’s two daughters, Hedvig and Mária. The former became Queen of Poland, the latter of Hungary, and at the same time, the competition for their hands began: who would marry Mary and become the new King of Hungary?

There were several contenders for the throne, but in the end, at the cost of intrigues and sacrifices, Zsigmond, who also risked his physical safety, rallied the barons behind him, so in 1385 he married Maria and on the last day of March 1387 he was crowned King of Hungary and Croatia by Himházi Benedek, Bishop of Veszprém in Székesfehérvár. The coronation was not performed by the archbishop of Esztergom, but the event was different from the previous custom.

“The day before, Zsigmond swore an oath to abide by the points laid down by the chief priests and barons as conditions for his coronation. (This unusual act became customary for the kings who reigned after Zsigmond. ) Accordingly, the future king undertook to preserve the ancient freedoms of the country; protect the rights of all; grant a general amnesty; cancel his donations; annul family contracts made for his accession; appoint only Hungarians to the royal council and offices; not to donate lands to foreigners, nor to ask the Pope for ecclesiastical benefices for them. These obligations were not very new compared to the practice in other countries at that time. But the real content of the contract came later: Zsigmond had to ally with the lords who had made him king, and at the same time he empowered them to enforce his promise by force in case of non-compliance”. ( C. Tóth Norbert)

Zsigmond made a pact (“League”) with certain groups of barons for the throne, as the dwindling royal power no longer allowed him to play politics independently of everyone else. According to the agreement, Lackfi István became the new palatine. Although Zsigmond won the crown, he was forced to cooperate with the League and satisfy the territorial demands of the barons. The castle system, which had been restored at the beginning of the Angevin era, collapsed because Zsigmond donated half of the royal estates. At the death of Louis the Great, the king still ruled over 160 of the country’s 300 castles, but under Zsigmond’s reign, this number was reduced to 70. However, the system of noble counties was strengthened.

It was during this period that the vast estates of the magnates began to emerge. About 20 percent of the country’s castles remained in royal hands. As can be seen from the above, the ruler’s hands were tied by the barons, but he was still able to gradually strengthen his position. He supported the organization of the nobility into an order by including them in the Diet, while at the same time strengthening their role in the counties.

Highly educated and sociable (he spoke seven languages and was a fan of jousting), one of the most important measures and moments of Zsigmond of Luxembourg’s reign was to support the development of cities with privileges. He carried out large building projects in Visegrád, Buda and Székesfehérvár. In Buda, from the late 1370s, King Louis the Great began building a large palace, which Zsigmond continued on an even larger scale, finally moving his court to Buda in 1408. In the center of the country, he founded the first university in the capital. At the request of the monarch, Pope Boniface IX issued the first charter of the University of Óbuda on October 6, 1395.

The now-ruined Buda Palace complex was once a wonder to behold. It can be said that Buda was the center of Europe at that time, where emperors, kings, and princes were received. For the first time in history, the German Imperial Diet was convened outside the borders of the Holy Roman Empire, in Pozsony (Bratislava, Pressburg). In 1397-1409 he had a hunting lodge built on the shore of Lake Öreg in Tata (the fortress was later rebuilt by King Matthias Corvinus on the model of Italian moated castles).

www.varlexikon.hu

Zsigmond enacted progressive laws, brought the church under his control, and taxed church property. He favored practical innovations that brought new ways of thinking in institutions, systems, and military technology. He seized the thrones of Croatia, Germany, and Bohemia (making him the most famous ruler in contemporary Europe).

The monarch tried to consolidate his power in Hungary. He raised new men to the baronial rank, such loyal lords as Cillei Hermann, Ozorai Pipó, and Stiborici Stibor, but the rise of the Báthory, Rozgonyi, Tallóci, and Garai families also began at this time. Since he brought to power common nobles instead of barons, the whole League was against him already in 1401. He was captured, but Garai Miklós heroically gave himself up as a hostage in exchange for the king. On one of these perilous occasions, Tar Lőrinc saved Zsigmond’s life, fighting against several foes, while receiving heavy wounds.

After Zsigmond regained the throne, the Garai-Cille League was formed, bringing together the royal barons. As a result of this agreement, Zsigmond, widowed by the death of his pregnant wife Mária in a riding accident in 1395, broke off his engagement to Margaret Piast, Princess of Brieg, in 1401 and in the same year became engaged to Cillei Borbála, whom he married in 1405.

To consolidate his position, Zsigmond tried to place the Hungarian Church, primarily as a source of material resources, at the service of royal power. In 1404, he issued a decree making the issuance of papal bulls subject to royal concession (placetum regium – royal right of veto), which meant that even the pope’s decrees could only be promulgated in the country with the king’s consent.

The economic development of the 14th century led to an increase in the number and population of towns, especially the free royal towns. There were only a few free royal cities, such as Buda, Pozsony, Bártfa, Eperjes, and Kassa, but the urban development in Hungary was significant in comparison with itself. In 1407 Pásztó became a market town where Tar Lőrinc was the landlord. Since the inhabitants of these towns were obliged to support Zsigmond, they played an important role in the political stabilization, as none of them wanted to be subordinated to the nobility or lose their privileges.

The monarch increased the number of walled cities, encouraged trade between cities, and ordered the standardization of weights and measures. The standard weights and measures remained those used in Buda (Article I of Act I of 1405: “that the weights and measures of fluvial and solid bodies throughout the country shall be applied to the weights and measures of the city of Buda”). His economic laws were a kind of early mercantilism, imposing protective duties on foreign merchants, who were only allowed to sell their goods in larger quantities, while domestic merchants were free to trade. The prohibition of the export of precious metals and all unprocessed ores and the import of salt served to increase royal revenues.

In 1405, the king issued municipal decrees, laws that strengthened the position of towns and their citizens; among other things, he confirmed the right of towns to judge their inhabitants independently and gave their judges the right to use the sword. The preamble to the decrees of 1405 already raised villages to the status of market towns and rural towns to the status of cities, and ordered the construction of defensive walls. In 1435, the fourth order, the bourgeoisie, was represented in the Diet.

In 1408, Zsigmond created the Order of the Dragon with 24 baronial families to strengthen the Royal League and fight the Turks. Its members, as barons, were given a seat in the royal council and were also granted estates. Read more about the Order here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/swords-and-sabers/ceremonial-sword-of-the-dragon-order/

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Photo: Szöllösi Gábor www.varlexikon.hu

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/albrecht-durer-1471-1528-and-hungary/

In 1389, Zsigmond’s first Balkan campaign conquered the castles of Borač and Čestin in the area of present-day Kragujevac. This was the first time that a Hungarian king took possession of Serbian territory beyond the borders of the Macsói (Mačov) Banate region. After that, the Turks and Serbs joined forces to invade Hungary for the first time in early 1390. In July of the same year, Count Sárói László of Temes County defeated another Turkish-Serbian invasion force at Vitovnica.

Zsigmond’s second campaign in the Balkans in 1390 did not bring any significant success (the probable aim was to take Ostrovica). Meanwhile, the Turks captured the key castle of Galambóc (Golubac, Taubenberg, Gögerdsinlik), which Zsigmond tried to retake in December of that year, but without success. More about Galambóc Castle’s history:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/ottoman-occupied-lands/galamboc/

In 1391, the Bosnian king Tvrtko I died, and Zsigmond announced a campaign in Bosnia, but in the end, he (probably) made a truce with the new king, Dabiša, and went with a small army to the Szerémség (Sirmium) region against the Serb-Turkish troops who were ravaging it. (The other half of the army, led by Perényi Miklós, a Ban (Duke) of Szörény, fought – successfully – in the Temesköz region against the invading Turks). The Turks destroyed Szávaszentdemeter, Nagyolaszi and Nagyeng.

Zsigmond’s third Balkan campaign followed. The Hungarians fought the enemy at Nagyolaszi (now led by Zsigmond) and then at Nagyeng, but the second battle also ended in a draw. Maróti János, whose younger brother Maróti Dénes had been captured by the Turks (at Nagyolaszi), distinguished himself in the battle of Nagyeng.

At the beginning of 1392, the Turks invaded the frontier in the Temes region with greater force than ever before, and Zsigmond even asked (and received) his brother Vencel for help in the Fourth Balkan Campaign (and even English knights came from his brother-in-law, King Richard II). As a result, the Turkish armies (led by Sultan Bayezid himself) did not engage in open battle, but only hindered and delayed the movement of the Hungarian armies until they were exhausted and turned back.

Zsigmond’s fifth Balkan campaign took place in 1395. Once again, Zsigmond personally led the war, this time in Wallachia. He defeated the troops of the pro-Turkish Voivode Vlad and restored Voivode Mircea, who had been deposed in 1394, to the throne. After the withdrawal of the Hungarian army, the Turks invaded the counties of Krassó and Temes but were defeated near Csák by Csáky Antal and Marcali Miklós, the lords of Temes.

Emboldened by his success, Zsigmond wanted to drive the Turks from all of Europe, but in 1396 he suffered a decisive defeat at Nikápoly (Nicopolis) at the hands of Sultan Bayezid’s army, which you can read about here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/1372-1490/the-battle-of-nicopolis-nikapoly-1396/

He went on the defensive against the Ottoman Empire, recognizing that the country needed to be on the defensive, and built the southern system of forts (which defended the country until 1521). Because of the proximity of the Turks (Serbia became a Turkish vassal state), he built a system of forts in the south of the country under the command of the Italian Pippo of Ozora.

He built a complex defense system in the southern lands. The southernmost parts were the buffer states (e.g. the Wallachian Plain). Then there were the Banates regions along the southern border, and the third line was the first line of fortifications, centered around Nándorfehérvár (Belgrade). In 1428 an unsuccessful attempt was made to retake the castle of Galambóc from the Turks. During the battles in the south, he lost Dalmatia, which was again under Venetian rule.

He created a new military system: landlords had to provide one mounted archer for every 20 (later 33) serfs. (According to some historians, the Hungarian word for a light cavalryman called “huszár” (hussar) derives from this law, since “húsz” stands for 20 in the Hungarian language, while “-ár” is a suffix often used to describe trades). Zsigmond frequently ran into financial difficulties to raise revenue, often levying extraordinary war taxes or mortgaging castles and villages. In 1412, for example, he mortgaged 16 towns in the Szepes (Zipt, Spiš) region to the Polish king for 37,000 Czech guilders. These settlements were returned to Hungary only after the first partition of Poland in 1772. You can read more about it here:

The king had the southern fortress system built at great financial cost because of the Turkish threat, but when Murad II (1421-1451) advanced in the Balkans, he considered other solutions. His idea was to transfer the administration of the Szörényi Banate from the Wallachian voivods to the Teutonic Knights, who would then guard Orsova, the entrance to the Lower Danube. This was not a new solution, as he had wanted the Teutonic Knights to defend the southern border after the defeat at Nicopolis in 1396, but the Grand Master preferred to expand into Russian territory.

Redewitz planned a complex defense system with a garrison of 1370 men, 550 cavalry, 328 artillerymen, and 1400 Danube sailors. According to his calculations, 314,822 forints would have been needed to cover the soldiers’ salaries, a huge sum.

On December 8, 1437, when he was about to expel his wife Cillei Borbála from the Moravian town of Znojmo by besieging it, the king, sensing that the end was near, put on his imperial robes, crown, and last rites, sat on his throne, ordered a funeral mass and died the next day sitting on his throne. He was buried in Várad (Nagyvárad, Oradea) next to his first wife, Anjou Mária.

In the absence of a male heir in his kingdoms, he nominated the husband of his daughter, the talented Habsburg Albert, as his successor. Albert was the only Habsburg king who was loved by his Hungarian subjects and reigned from Buda. Zsigmond’s supposed natural son was Hunyadi János, born to Erzsébet of Morzsinai but this is not proven. You can read more about Hunyadi János, whose bright career began during Zsigmond’s rule here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/hunyadi-janos-1407-1456/

Sources: Rubicon Magazin, Wikipédia, és National Geographic (Jeki Gabriella)

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all