Hungarian sabers, 15th-17th century

In this post, I will list a few nice Hungarian sabers from the 15th-17th century.

Let me begin with an early Hungarian saber from the 15th century:

This is a Hungarian saber from the end of the 15th century, now it is owned by a collector somewhere in the Netherlands.

Swords with S-shaped guards and cat’s head pommels are deemed to be medieval Hungarian. The cat’s head pommels are thought of as of Venetian (on the Adriatic sea) origin. This sword looks like a hussar sword with a cat’s head pommel. These hussar swords later had almond-shaped pommels (late medieval times) and the crossguards became smaller/shorter.

The saber of Bebek György

This saber belonged to Bebek György, the infamous but brave Hungarian knight who died in 1567. The saber is on display in the Hungarian National Museum, Budapest now. According to the sources, this saber was given by Sultan Suleiman I to Bebek György in March 1565 when he was released from the captivity of the Ottomans. As it was, Patócsy Zsófia, his wife, had ransomed him by sending 50 Turkish prisoners of war, and 10,000 gold Ducats to Istanbul, along with lots of gold and silver jewelry and vessels.

The Sultan summoned him to the Divan on 6 March, and released him from his captivity but told him strictly not to fight any more against the Ottomans, and be loyal to János Zsigmond. He gave him an expensive kaftan and a nice Arabic horse with a similarly expensive saddle on it, then gave him 10-10,000 silver Akche coins in his pockets so as to go home as it was befitting to his rank. Other pashas gave him four more horses, and the Sultan gifted him with this special saber that must have been designed for him.

The exciting part of the saber is the drop-shaped tip of the grip which is a typical Hungarian feature. The development of the Hungarian saber began to differ from the Turkish sabers in the middle of the 16th century, which is why this saber is so interesting.

After the death of Bebek György, his widow, Patócsy Zsófia must have inherited the famous sword. She was famous for defending the castle of Szádvár against the Habsburg troops, then she left for Transylvania where she died in 1583 in Küküllővár. The famous saber surfaced again in 1896 when it was on display during the exhibition organized for the Hungarian Millennium. At that time, it belonged to the armory of the Habsburg king. There were lengthy negotiations about the ownership of the saber after the Treaty of Trianon, and finally, the saber was given to the Hungarian National Museum.

You can read more about Patócsy Zsófia and the castle of Szádvár on my page:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/kingdom-of-hungary/szadvar/

and: https://www.szadvar.hu/2021/07/bebek-gyorgy-szablyaja/

Saber with Scabbard

It is an Eastern European saber, probably from Hungary. We can date it back to around 1550. Some think it is a late-period Ottoman “kilic”, though.

Material: Steel, gold, wood, leather

Length: 41 1/2 in. (105.4 cm);

Length of blade 35 5/16 in. (89.7 cm);

Weight: 3 lb. 7 oz. (1559 g);

Weight of scabbard: 1 lb. 11 oz. (765.4 g);

Weight of strap: (c) 4.6 oz. (130.4 g)

According to others, the handle is the same as in the Titian painting of Cardinal Ippolito de Medici (1511-1535). The scabbard is later in the 1500s. Probably close to the 1535 timeframe. Here is the painting:

It is on display in New York, in the Metropolitan Museum.

The Saber of Zrínyi Miklós (Niokola Subic Zrinski) 1508-1566

This blade can be seen now on display in Vienna.

In his chronicle, Samuel Budina emphasized the role of Zrínyi’s sabre in the outbreak of the siege of Szigetvár Castle at the beginning of September 1566:

“He ordered his servant to give him his sickle-shaped swords. These were decorated with gold and silver and are called sabres. After testing them, he chose one of the four that had belonged to his father and said: “Of my old swords, this is the one with which I earned my first glory and honor, with which I gained all that I have. With this sword in my hand I will now bear all that the judgment of God has laid upon me. So he took his sword in his right hand, went out of his house, and commanded his round shield to be brought after him. Beyond that, he would wear no other armor, no armor, no helmet.”

One of the preserved sabres of the hero of Szigetvár is in the armoury of the Museum of Fine Arts in Vienna. But the description above that the saber from Vienna cannot be identical with the one used in the outbreak in Szigetvár. The date and initials on the hilt cap indicate that it was made or modified by order of Zrínyi Miklós.

According to Szendrei János (1896): “The blade is 83 cm long and 3.7 cm wide, the handle 11 cm. Crossbar 22 ctm. Weight 1 kilo 700 grams. The shape clean Hungarian, similar to the case in the 16th and 17th century in Hungary and Poland.”

Attempts to retrieve the Zrínyi sword were made after the collapse of the monarchy (1918), when Hungary made considerable efforts to recover the objects that had previously been sent to Vienna. The Hungarian-Austrian negotiations lasted for more than ten years, but none of the relics associated with Zrínyi were recovered. The legal basis for the negotiations was the Treaty of Trianon, Article 177 of which stated that these objects could not be returned to Hungary.

Source: https://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00018/00275/pdf/EPA00018_hadtortenelmi_2018_01_003-027.pdf

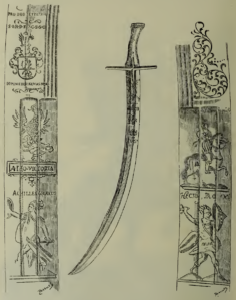

The Saber of Rákóczi László (1633-1664)

This can be read on the typically Hungarian-like blade: GLORIA VIRTVTEM SEQVITV (R) and HECTOR TROJANVS. On the inner side, you can see the COA of the Rákóczi family with the text PRO DEO ET PATRIA. Below that, the dim letters: C.(omes) L.(adislaus) R.(ákóczy) D.(e) F.(els) V.(adász) C.(omes) S.(arosiensis S.(iculorum) C.(omes)? Under the COA we can read: DOMINE DIRIGE VIAS MEAS. Then, an eagle with a sword cutting a Turk figure can be seen, and the text ADEO VICTORIA. There is a warrior holding a sword and one more inscription: ACHILES GRAECVS

The blade is 83 cm long, the entire length is one meter. It weighs (with the scabbard) one kilo and 380 grams. The blade is 4 cm wide. Rákóczi László lost his life in the siege of Várad castle on 27 May 1664. I am working on a longer article about him.

Source to this saber: https://hu.wikibooks.org/wiki/F%C3%A1jl:R%C3%A1k%C3%B3czi_L%C3%A1szl%C3%B3_(1633_vagy_36-1664)_kardj%C3%A1nak_fegyverkov%C3%A1csjegye.png

Hungarian saber (17th century, modern replica)

It is a Hungarian saber with Turkish characteristics, from the 17th century. The blade is 720 mm long, and the “fokél” (the sharpened inner blade of the weapon) is 250 mm long. Prince Báthori can be seen on the blade.

Source: Nádasdy Museum, Sárvár, Hungary

Hungarian saber, 17th century

The comment of the post writer: Hungarian saber with thumb ring for left-handed use. For reference only.

Source: http://Arms and armour Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire (posted by Oliver Pinchot)

A rare Hungarian saber from the 17th century

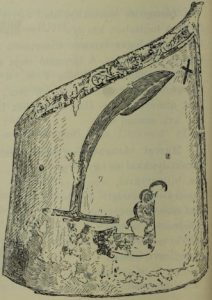

We can see a similar weapon depicted on this 16th-century Hungarian Hussar shield, too:

We can see a similar Hungarian saber on display in Dresden, too:

According to Lázár Tamás, the crossguard of this Hungarian noble’s saber is quite similar to it:

Hungarian Hussar Saber 17th Century

The blades for this saber model were produced in the Styrian manufactories in the 16th century. Usually, as a mark of the quality of the blade, they put marks in the shape of a jagged crescent.

Later, in the second half of the 17th century and during the 18th century, symbols indicating the political or religious commitment of the saber-bearing warrior were placed, the figures of the sun, crescent, star, Mother of God, Immaculatae, and various inscriptions were placed.

At that time, wars against the Ottoman Empire were being waged in the regions of Austria and Hungary, and therefore the religious affiliation of the saber-carrying warriors was important. This saber is also engraved on one side of the blade:

“IN. I. IHS M …..”. On the other side of the blade is engraved an inscription in Latin from the Gospel according to John 1:14: “ET VERBUM CARO FACTUM EST HABITAVIT IN NOBIS) which in translation reads: AND THE WORD BECAME FLESH AND DWELL AMONG US.

Source: Miroslav Poljanec

Hungarian sabers, 17th-18th century

These 17th-18th century blades are in the Arsenal of Graz, Austria:

This nice 17th-century saber was on sale on the internet a few years ago: modern reenactors often use 18th-19th century blades for training:

More Hungarian sabers

after 1650

These sabers are in the private collection of Fekete Artúr, Hungary. (1680-1710)

More sabers are coming soon…

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

[wpedon id=”9140″ align=”center”]