„Delirant Reges, plectunur Achivi” – The people pay for the foolishness of the kings

How King Matthias Corvinus strengthened his power and how the people paid for his foreign wars…

King Matthias was born in 1443 in Transylvania, in Kolozsvár (Cluj, Klausenburg), and his family had large estates there. No wonder he wanted to take the reins of Transylvania in his strong hands, knowing how important a part of the kingdom it was.

How did Zrínyi Miklós (Nikola Zrinski) write about it some 200 years later? At the same time, see how Zrínyi criticized King Matthias for waging war against the Bohemian king under the pretext of religion; he also explained his thoughts on religious wars in more detail.

You can read about the beginning of King Matthias’s reign here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/the-beginning-of-king-matthias-reign/

Read Zrínyi’s thoughts. Let’s ask ourselves why these things could be timely at his age:

“Next, Transylvania and Moldova have rebelled, daring to kick against the luck of the king. Transylvania protested about the size of its tax but it was not a just cause. For the king needed the tax, especially a king like Mathias had been…The people have no peace without an army, but there is no army without getting paid, and there is no payment without taxes. (…) We can observe the quickness and the diligence of the king: he did not leave time for spreading the plot against him: he reacted at once.”

"The second observation is that this king was that he was masterfully able to carry out something in more than one way. (…) Moldova could not have been tamed without a weapon, so he punished it with the weapon. Transylvania has admitted its fault, so the king had mercy on it but cast some of the noblemen out of the country. Some of these had not left the country by the given time, trusting in the leniency of the king. The king gave them to the hand of the executioner so the rest could learn not to play anymore with the mercy and the law of the king. Alike, there is no greater sin before God than daringly insisting on God`s mercy.”

“The third observation is that the king was bustling to fight against the Moldovians; while other kings would have run away immediately from there, he was bravely waiting for his enemy and even defeated it, though he got wounded himself one cannot avoid getting wounded because „virtus vulnere viret” – the brave is decorated by wounds.”

The background of the Hungarian-Bohemian relations:

When King László V of Bohemia and Hungary died unexpectedly and without an heir at the age of 17 in November 1457, the most powerful rulers of the Ottoman-threatened and strife-torn Kingdom of Hungary sat down to negotiate. In January, the leaders of the two most powerful aristocratic parties, Szilágyi Mihály and Garai László, agreed in Szeged to elect Hunyadi Mátyás king, giving Szilágyi governorship, allowing Garai to keep his estates and his position as a Palatine, and for Matthias to marry his daughter Anna.

It was a rare and exemplary alliance, the lords putting aside their grievances for a common goal, but there was one serious obstacle: Matthias was in Prague at the court of the Bohemian governor, George Podjebrád. The young Matthias was taken into custody in Prague right after the death of King László V. He was there not of his own free will but as a hostage to keep the Hunyadi party in check. The bishop of Várad, Mátyás’s tutor, János Vitéz, an eminent Latin scholar, was already in the Bohemian capital negotiating for his release.

Vitéz did not know about the deal in Szeged, so he also made his own, the most important point of which was that Mátyás would marry Podjebrád’s daughter, as the age of the then 9-year-old Katalin allowed. Podjebrád was already within an arm’s reach of the Czech throne, and Vitéz correctly assessed that a Czech-Hungarian alliance sealed by marriage would be a powerful force against both the Ottomans and the Habsburgs.

The young Hunyadi returned to Buda with two candidates for his wife, but at the age of 15, he made a wise decision: he chose Catherine. In doing so, he had stirred up trouble with his uncle, who had made an oath of allegiance to the Garai family, but Mátyás chose the more politically rewarding solution:

‘…wishing to repay the good deeds he had done, we promised him, even before we were elected to the royal dignity, that we would enter into an indissoluble friendship, brotherhood and brother-in-law relationship with him. Now, therefore, we desire to assure Governor George that, after our election to the royal dignity, we have not changed our former intention and will.” (Declaration of Matthias Hunyadi in Strasznice, 9 February 1458)

Catherine and her twin sister Sidonia were born in November 1449 in the spa town of Poděbrady, on the family’s ancestral estate. Their mother, Kunigunda of Sternberg, died of childbed fever shortly after giving birth, but the girls fortunately survived.

The family quickly rose upward on the social ladder, with George Podjebrád becoming governor of Bohemia in 1452, governor of the Bohemian lands of King László V, and monarch from May 1458, virtually sealing the ‘deal of the century’ by making his daughter a Hungarian queen.

The wedding was to take place the following year, but the bride’s tender age and some complications in Hungary delayed it by several years. Catherine came to Hungary at the age of 11, in early 1461, and according to Antonio Bonfini, Matthias: “She brought her to Hungary with great pomp and loved her very much. The Bohemian lords escorted the bride to Trencsén; here she was received by the Hungarian lords and high priests with royal pomp, and led to Buda, where they had a great feast.”

Not right away, because the wedding was held on 1 May 1463 in the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption in Buda, now known as the Church of Matthias. The queen was under 14 and soon became pregnant. This was important, not only because there was an early chance of an heir to the throne, but also because, under the terms of the Treaty of Vienna, Matthias had regained the Holy Crown from the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III on condition that, if he was childless, the Habsburgs would inherit the throne of Hungary.

When the queen gave birth to a son in March 1464, there was great joy in the Kingdom of Hungary, but it did not last long: on 8 March, Catherine, like her mother at his birth, died of childbed fever, and the infant heir to the throne died. At the time, no one could have known what tragic consequences this would have. Matthias married again 12 years later, in 1476, to Beatrix of Aragon, but she was unable to bear him a child. The ‘last great Hungarian king’ thus died without a legitimate heir in 1490.

The Bohemian conflict

The already existing conflicts of interest between the Bohemian and Hungarian sides were then further exacerbated. The Bohemian king did not sufficiently support Matthias against the Czech mercenaries in the Highlands and against Emperor Frederick III. At the same time, the Pope, despite his conversion, considered the Bohemian king a Hussite and worked to overthrow him. In 1465, Matthias had already indicated his willingness to fight both the Bohemians and the Turks in exchange for papal support.

In the spring of 1468, the son of the Bohemian king, Podjebrád Viktorin, the Moravian captain-general, launched an attack against Emperor Frederick III. The Emperor asked his adopted son, King Matthias, for help. Antonio Bonfini put it this way: “The Hungarian king was also in a difficult domestic political situation, which is why he decided to go to war.” These were the words of King Matthias in his declaration of war against Podjebrád on 25 April 1468:

“You have declared war against our father, the Roman Emperor, though you know well that we have a treaty with him which obliges us to give him aid. And while you have attacked our friends without sufficient cause, you have also long since provoked us to many injuries and offenses. These our love of peace has hitherto borne with patience, but now we must seek in our arms the assurance of peace, which we can no longer find in your words and characters.”

The Hungarian monarch was ostensibly complying with the wishes of the Pope and the Emperor, but in reality, he undertook a protracted and unsuccessful war against his former father-in-law for the Bohemian throne and to prevent the expansion of the Jagiellonian dynasty.

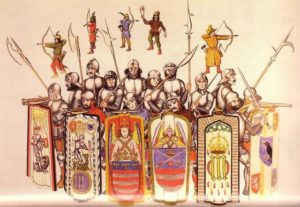

However, Matthias misjudged the situation. From then on, the Bohemian War tied up the country’s forces for a decade, and the king received almost none of the money promised by Frederick III for this purpose. The anti-Pojebrád Czech Catholic noblemen league was weaker than expected, and the Czech royal army, then considered the best soldiers in Europe, was stronger than expected.

On the other hand, the Bohemian war also had a positive effect on the country: Matthias was able to employ his mercenaries (who were also largely Czechs), and wars at this time could sustain themselves and the armies involved to a certain extent, as they lived largely on plunder. Winning battles and sieges also provided income for the barons through their bands. Militarily, the war produced mixed results.

In May 1468, Matthias took Třebíč in Moravia but was himself wounded. In February 1469, at the siege of Chrudim, the king went on a reconnaissance in disguise, according to tradition, and was captured but released because of his disguise. It was here that the legend of the king in disguise, which later became so widespread, first appeared. It is a fact, however, that at Vilémov, the Bohemian king’s troops surrounded Matthias’s forces. The Hungarian monarch then requested a meeting with Podjebrád, which was held in a hut. A truce was agreed upon, and another meeting was arranged at Olomouc.

Podjebrád, as Electoral Prince of the German Empire, agreed to support Matthias in his election as King of Rome, as already promised by the Pope and the Emperor, which was a stepping stone for Matthias to gain the title of German-Roman Emperor. In return, Matthias agreed to reconcile his former father-in-law with the Vatican. Both sides were taking an impossible step because Emperor Frederick III had already given the title of King of Rome to Charles the Bold, Prince of Burgundy, and the Pope was in no way prepared to make any concessions to the Hussite king. In any case, Matthias was thus able to escape from his tight military situation.

On 3 May 1469, the Catholic Czech orders elected Matthias King of Bohemia in the cathedral of Olomouc. This left the country with two kings, and the possibility of an agreement between the two was abolished. In addition to the Czech Catholic orders, Matthias was accepted as king by the Catholic tributary provinces of Moravia, Silesia, and Lausitz, as well as by the mainly German-speaking towns (especially Wroclaw / Breslau / Boroszló). The fronts were stiffened.

Regarding the Bohemian War in 1468, Zrínyi wrote the following:

“Then, Matthias’ army attacked the Bohemian king; it was because of the instigation of the Pope of Rome and the Emperor of Rome, and the pretext was the religion of this war. I do not know how we must praise this campaign: it was not righteous, but it was rather necessary. Our present world (without telling you the name of a ruler in particular) makes war under the pretext of religion when it wants to add color to its campaign; but where is it written in the laws of the Christians or the teaching of our Lord Jesus that we must convert the heretics and the Turks to our faith? Certainly, I cannot find it anywhere, but instead, I find that we should suffer peacefully, enduring everything. Our faith does not want to shed other blood except its sons, for the glory of God.”

"

The next clash was because of Bohemia in 1471

In March 1471, King George Podjebrád of Bohemia died, but the Bohemian estates did not choose Matthias, who already held the title of King of Bohemia, but the eldest son of the Polish King Casimir IV, the then 15-year-old Polish King Ulászló Jagelló, to replace him.

In the wake of this failure, and largely because of the heavy domestic tax burden caused by the Bohemian War, a rebellion led by Vitéz János broke out against Matthias. In the new situation, with Bohemia having a devout Catholic ruler instead of the Hussite Podjebrád, Matthias’s Bohemian war lost all legitimacy, although, on 28 May 1471, the papal legate Lorenzo Roverella in Jihlava confirmed Matthias as King of Bohemia. You can read more about the war of Matthias in Boroszló / Wroclaw:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/king-matthias-at-boroszlo-wroclaw-breslau/

On September 20, 1471, Prince Casimir Jagelló, son of King Casimir IV of Poland (reigned 1447-1492), who had claimed the Hungarian throne at the request of the conspirators led by Vitéz János, declared war on Matthias. With the Polish invasion that started as a result of the noblemen’s conspiracy, Matthias’s rule was seriously threatened, but thanks to the king’s wise tactics, he eventually resolved the conflict without bloodshed.

Thanks to his speed and wisdom, the king was finally able to take control of events, and by the middle of July he was in Buda, where he bribed the conspirators he found there with fine words and promises – for example, he promised Ujlaki Miklós a royal crown in Bosnia – and then in September he called a parliament to redress the grievances.

Thus, by the fall, the overwhelming majority of the nobles, offended by their neglect, had returned to Matthew’s loyalty and were ready to defend the king against the expected Polish attack. Of course, Prince Casimir and the Krakow court were unaware of these developments, so on September 20, the pretender sent a mocking declaration of war to Matthias, claiming the Hungarian crown for himself and relying on the crowds behind him.

The Polish army invading the Highlands soon experienced unpleasant surprises, because in October only a few noblemen joined Kazimierz’s army in Sáros, while in Kassa the enemy armies of Csupor Miklós and Szapolyai Imre were waiting for the prince. Those around the pretenders to the throne were at a loss, as the former conspirators were waiting for them with weapons, contrary to the warm welcome they had hoped for, so the Polish army marched first through Szikszó to Hatvan, and then in November to the castle of Nyitra.

Although Matthias had a considerable advantage over Casimir, the king was content to shadow the marching prince with his troops, thus practically chasing the enemy back and forth in his country. By the end of the fall, most of the unpaid mercenaries had left Casimir, who found himself in a difficult position as Nyitra was surrounded by Matthias’s armies, though not besieged.

The King believed that the Poles were no longer a threat to his rule, so he soon left Nyitra and marched towards Esztergom to fight the main organizer of the uprising, Vitéz János. The archbishop and the monarch were soon reconciled through the mediation of the barons, but Vitéz soon gave Matthias reason to distrust him again and ended his life in the captivity of his greatest enemy, Beckensloer János, Bishop of Eger. Read more about the life of Vitéz János:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/zrednai-vitez-janos-c-1408-1572/

A similar fate befell Vitéz’s nephew and patron, Janus Pannonius, Bishop of Pécs, who, seeing Matthias’s victory, fled from Buda, first to conspire in Pécs, then to Italy, until death overtook him in Medvevár. Matthias was thus able to overcome the most dangerous conspiracy threatening his rule without bloodshed, but the price of victory was the life of one of his best friends and one of the most talented poets of Renaissance Hungary.

The war in 1477

On June 12, 1477, Matthias I had to declare war on Frederick III. The reason for the declaration of war was that the Emperor had not enrolled Matthias in the fief of Bohemia, had attacked his Austrian allies despite the armistice, and had not assisted Matthias against the Turks. Following the Hungarian successes, the war was concluded with a peace treaty on 1 December, which brought moral and financial benefits to Matthias.

However, the peace did not last long, and what was described was not fully realized. Thus, in 1477, under the terms of the Treaty of Gmunden-Korneuburg, Emperor Frederick also recognized Matthias as King of Bohemia and took the traditional oath of allegiance to him. Afterward, both Ulászló and Matthias resumed negotiations, and in 1478, they concluded the Peace of Olomouc, which was solemnly ratified on 21 July 1479. This confirmed the status quo, under which they mutually recognized each other’s titles as Czech kings, with Matthias retaining Moravia, Silesia, and Lausitz, and Bohemia in the narrower sense of the term remaining in Ulászló’s hands. Under the terms of the peace, Ulászló could only redeem his territories after Matthias’s death for 400,000 gold Florins.

Ulászló remained the Electoral Prince, but Matthias also took the first step towards obtaining it. However, keeping the army abroad was both an advantage and a disadvantage. The pay itself resulted in a large outflow of gold, but its “supplement” (plunder and looting) did not destroy Hungary.

Source: Partly from Hungarian Wikipedia and Magyarforum

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: