Zrínyi Miklós, the poet and general (1620-1664)

His family’s motto was „ Sors bona, nihil aliud” (Only good luck, nothing else) but he used to add that God gave the fortune and showed the way. Human efforts must be made, of course: „…the human mind never gets so much help for the valiant soldiering or for any other thing as from learning and reading history.”

Zrínyi Miklós was born on 3 May 1520, his father was the Croatian Juraj Zrinski (Zrínyi György), and his mother was the Hungarian Széchy Magdolna. His brother, Péter (Petar) was born in 1621. According to a recently discovered letter written by his father, Miklós was born not in Ozaljl castle on 1 May but in Csáktornya castle on 3 May 1620. His godfather was Pethő Gergely, Vice Comes of Varasd, and his godmother was his second wife, Patatics Anna. The boys’ mother died soon after Péter’s birth, and they lost their father in 1626. Let us see how the chronicler, Pethő Gergely wrote about it…

The death of Zrínyi György in 1626

The young Zrínyi Miklós

King Ferdinánd II appointed five tutors to take care of the education of the Zrínyi orphans, their leader was Archbishop Pázmány Péter. The Zrínyi family had immense lands, Miklós inherited their northern part while Péter the southern, Croatian region.

With Pázmány’s help, Zrínyi became an enthusiastic student of Hungarian language and literature, although he prioritized military training. The two brothers attended the Jesuit College of Graz, and then they studied in Vienna and Nagyszombat (Trnava). Masterfully, Miklós spoke at least six languages: Croatian, Hungarian, German, Italian, Turkish, and Latin.

Miklós was given the rank of “Royal stablemaster” in 1628. From 1635 to 1637, he accompanied Szenkviczy, one of the canons of Esztergom, on a long educative tour through Italy where the young aristocrat was received by the Pope and Zrínyi gifted him with a collection of his poems written in Latin. Having returned home, he and his brother split their lands among each other. He remained in the Trans Danubian Region and the Muraköz area, and his headquarters were at Csáktornya (Cakovec). Here is more about Csáktornya castle:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/kingdom-of-hungary/csaktornya/

The Zrínyi family raised the money for their wars against the Ottomans from their income: they traded with salt, grain, wood, and cloth. They had been herding 40,000 grey cattle annually to the marketplace of Légrád (Legrad) to avoid paying taxes to Vienna. They made a business contract with the Ottoman Turk Pasha of Kanizsa castle along with the Venetian merchants to trade. After that, they used their armed men to herd the cattle to the Adriatic harbors. It all looked very close to treason but the family was reasoning to the Court that they needed the money for the defense of their homeland, they had to get it from somewhere because Vienna couldn’t have financed the wars alone. The Zrínyi family even had the right to mint coins on their own.

Zrínyi on the battlefield

In 1645, during the closing stages of the Thirty Year Wars, he acted against the Swedish troops in Moravia, equipping an army corps at his own expense. At Szkalec he scattered a Swedish division and took 2,000 prisoners. At Eger, he saved the life of King Ferdinand III, who had been surprised at night in his camp by the offensive of Carl Gustaf Wrangel. Although not enthusiastic about having to fight against the Hungarians of Transylvania, subsequently he routed the army of Prince Rákóczi György on the Upper Tisza river.

Then, he served under the command of General Johann Freiherr von Götz and Hans Puchheim and they scattered the mounted Hajdú unit of Ibrányi Mihály. According to the chronicle of Ráttkay György, he threw himself into combat and cut down several Hajdú soldiers in Tiszalúc / Ónod region. The young Miklós was able to seize the flag of Ibrányi, by cutting down the flag bearer. Then, he rode back triumphally to General Götz to show the trophy of war. You can read more about the connection between Zrínyi and the Hajdú warriors here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/the-hajdu-warriors-in-zrinyis-winter-campaign-in-1664/

For his services, the Emperor appointed him Ban (Duke) of Croatia in 1647, and he received the rank of Major General, for the first time among the Hungarian noblemen. At the coronation of Ferdinand IV, King of Austria, King of Germany, King of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia, he carried the sword of state.

During 1652–1653, Zrínyi was continually fighting against the Ottomans — nevertheless, from his castle, he was in constant communication with the intellectual figures of his time; the Dutch scholar, Jacobus Tolius, even visited him, and left in his „Epistolae itinerariae” a lively account of his experiences. Tolius was amazed at the linguistic resources of Zrínyi, who spoke so many languages with equal ease. It was also noted how heroically Zrinyi had led his people to battles, often deciding the fight with his bravery.

In 1655, he attempted to be elected Palatine of Hungary; despite getting support from the petty nobility, his efforts were frustrated by failure as the king, because of Zrínyi’s good connections to the Protestants and the Hungarians of Transylvania, nominated Wesselényi Ferenc in his stead. It was the time when he wrote his short but adorable book about King Matthias Corvinus.

He wrote: “This king (=Matthias) had not spent the country’s wealth on either crazy buildings or insanely expensive receptions of guests or for making idiots richer but rather for his homeland’s strengthening, making it more glorious and famous. Who would not wish to help such a king with his own added value?”

In this work, Zrínyi was showing the idea of a strong national monarchy – and this idea was a counterexample of the current reigning foreign dynasty, governing from Vienna. Zrínyi, along with the contemporary public opinion regarded the Habsburgs as weak and if not outright ill-disposed towards the Hungarians, but they were minimally thought incapable of defending their Empire against the „rage of the Ottomans”.

There were opinions that Zrínyi, the Bán (Duke) of Croatia could be a better leader of the Hungarian Kingdom. Some say it was Zrínyi himself who may have hinted this much in his book about King Mátyás – he remarked, that the great king hadn’t come from any ancient dynasties but was elected freely by the Hungarian nobility. Still, it can be surely stated that Zrínyi has never wanted to get the crown openly. I based my whole series of historic articles about King Matthias on following Zrínyi’s footsteps, here they are:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/king-matthias-corvinus-1443-1490/

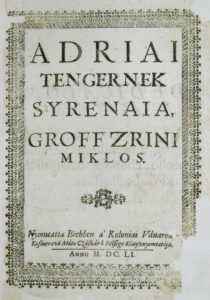

Zrínyi is also well known for his literary works. He is the author of the first epic poem in the Hungarian language, written in 1648-1649. Its subject is the heroic but unsuccessful defense of Szigetvár castle (1566) by the author’s great-grandfather. He wrote another famous political work about the Ottoman peril. Its title is „Do not hurt the Hungarians – An antidote to the Turkish poison.”

An antidote to the Turkish Poison- Do not harm the Hungarian

In Zrínyi’s last great work, he discusses why no one is helping the Hungarians to expel the Turks. No country will offer help merely out of goodwill. In his work, Zrínyi compared himself to the son of Croesus, who was mute, but at the siege of Sardis, when an enemy soldier wanted to kill the king, he cried out, “Do not harm the king! No one expected Zrínyi, the politician warlord, to speak up for his country any more than they once expected the mute king.

The author calls the inaction of the Hungarians a great mistake: he illustrates the consequences with examples: the Turks took Várad, and Jenő, and plundered Transylvania. He uses historical events to show that obedience and patience are useless in the face of the “Turkish beast”, but that heroism is all the more important: this was the case, according to Zrínyi, in the Greeks’ struggle against Xerxes.

His motto: “Better to die as a lion than to live as a donkey.”

Zrínyi believes that the first and most important thing to do is to create an independent national army. In the second part of the work, he explains his plan.

He makes a case in it for a standing army, moral renewal of the nation, the re-establishment of the national kingdom, the unification of the Kingdom of Hungary with the Principality of Transylvania, and, of course, driving the Ottomans out. He called for a radically new system for the country’s armed forces. He sets the permanent peacetime strength of the army at twelve thousand men (8,000 cavalry and 4,000 infantry). However, he also considers it necessary to maintain the army of the Borderland castles, so he plans to increase the size of the army considerably. It should be remarked, he was able to raise this army anytime from his resources.

He emphasized the importance of regular payment of wages and provision in kind so that soldiers would not be forced to wander and plunder. The question of who should form the standing army and who should train the soldiers is an important one. Zrínyi suggests that foreign – competent – officers should initially lead and train the troops. But he warns that this is only a temporary solution. In his opinion, both the soldiers and the officers should be chosen from among the peasants who had volunteered to serve, i.e. in his pamphlet he outlined the plan of a people’s army.

In this famous work, he lists the European countries from which help could be expected but demonstrates that they are not in a position to offer serious support. If we did receive foreign aid, it would mean that the Hungarians would no longer be in control. and in the end, he finds nobody to help us.

He writes: „Poland is one of our neighbors: from whom we can expect no help since he has been greatly weakened in recent wars and even now he is being pestered by the Russians.”

He adds: „Germany is our next neighbor. (…) Are we sure that the German nation would change his home peace and happiness to his peril? Are we in the knowledge that he would be so greatly indebted to Hungarians to risk his safety with such a monstrous beast as the Turks are? Has he forgotten the raids and pillaging of his land made by the ancient Huns of Attila and other Hungarians? Would he wish to pull round the Hungarians to fear them afterward? (…) I could barely believe it.”

„Italy is the third neighbor: it is too far away and the sea is between us, and his country is divided among many lords and princes … it would not give us great hope to receive help from there.” (…) „The great distance from Spain and his present wars in Lusitania cuts every consideration off; we do not need to talk more about it.” (…) „We do have something to say about the French nation. This nation is a valiant warring nation to be sure, but it is also obvious that we can’t hope for much good from him when he makes businesses and wars alone for his interest. (…) The French is insufferable when he is victorious and he is good-for-nothing when he is beaten and miserable.”

„I do not count the Russian nation because it would be a dream rather than reality – although I know that some people made up whatsoever hopes for themselves about Russia. (…) Their country is far away, their nation is rude, their war-making is good-for-nothing, their gallantry is ridiculous, their politics is inept, their empire is tyrannic; who would like their help!” (…) „England is almost a different planet, different nature, different warfare – we don’t need it and we can’t desire it.”

Finally, Zrínyi soberly concludes that we should count only on ourselves: „Alas, we have listed the whole Christendom and we can see that we cannot get the help that way that our entire freedom should be established on it. (…) So far those people’s aid who had been coming to our homeland to help us with great boasting is similar to the April wind (…) they had just robbed thoroughly our country and returned, leaving us alone.”

Zrínyi thought the internal situation was bad and wanted to force the Hungarians to take action against the conquerors. He called unity rather than internal strife the primary goal.

In financial matters, he does not call for an increased burden on the serfs, but for sacrifice on the part of the ruling class. The Church and the lords should bear the financial burden of the army, and the monarch should finance the cost of the Borderland fortresses. He concludes his work, which is not without occasional rhetorical twists, with faith in God and patriotism in action, but in one of his last thoughts he ends with an epic parable:

“Blessed be God, for this is a great vilitas (wickedness); and are we the Hungarians? We, Hungarians? But let us not call ourselves so. If we do not regain Várad, if we lose Transylvania, let us not fight afterwards, but now or never; let us flee the country if we are afraid. I have heard that there is plenty of land in Brazil; let us ask the King of Spain for a province, let us make a colony, let us become citizens. But if he who trusts in his God, loves his country, has a drop of Hungarian blood in him, let him cry out to God in heaven…”.

We might take a glimpse into Zrínyi’s thoughts if we read his letter to the Emperor in 1664:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/1541-1699/the-letter-of-zrinyi-miklos-in-1664/

Zrínyi’s opinion of religions

Zrínyi’s opinion about religious wars was plain: „I can hardly believe that it would either be kind before God or acceptable for men to attack all of our neighbors or any Christian princes only under the excuse of religion. Other reasons force us to fight against the Turks or against other enemies who either share our faith or not: there are more noble reasons than the religion.” Zrínyi had excellent French contacts, and he was also affected by the French idea of separating church and state and the concept of national absolutism.

We know that Zrínyi was a devoted Catholic but he was far from being a fanatic. He addressed the Protestant nobility like this: „I am on a different faith, but your lordship’s freedom is my freedom, if you are hurt, I am hurt, too. I wish the Prince had a hundred-thousand good Popists, a hundred-thousand Calvinists, and the same Lutheran warriors, they could save this homeland…” (…) „I hold a confiding Lutheran in higher esteem than an evil-hearted Catholic.” (…)

„Dear Sir, we have to keep our oaths even to infidels, how much more we should keep our words to our Christian brothers.” (…) „Attacking someone under the name of the religion is not right, it is against God’s mercy; also, it is a great sin and wrong to break our agreement with our enemy, under the cover of religion.” Here he refers to the contemporary belief that the Hungarian king Ulaszlo I had broken alliance with Sultan Murad II and because of his perfidy he was killed at the Battle of Varna in 1444.

Unfortunately, it was this politically open-minded thinking and activity that was observed with utter suspicion in Vienna. On the other hand, he had built a very good relationship with Prince Rákóczi II György of Transylvania. The Transylvanian Prince in the 1650s was believed to be a perfect ruler with capable characteristics and conditions to conduct the reunion of the country with success.

Zrínyi had very good contacts with the Germans as well as the French. He was in contact with the Polish, the Venetians, and the Pope, too. (Please, note that I use the Oriental name order for Hungarians where family names come first.) He wrote further books about military tactics that are worth reading, too.

In 1663, the Ottoman army, led by Grand Vizier Köprülü Ahmed, launched an overwhelming offensive against Royal Hungary, ultimately aiming at the siege and occupation of Vienna. One of the reasons for this attack was that Zrínyi had a new fort built in 1661, it was New Zrínyi Castle. Its role was to keep an eye on Kanizsa Castle.

When Vizier Ahmed was coming, the Imperial army failed to put up any notable resistance; the Turkish army was eventually stopped by bad weather conditions. The court concentrated all its troops on the Hungarian-Austrian border, sacrificing Zrinyi to hold back the Turkish army.

Right after this, Zrínyi made a treaty with Palatine Wesselényi Ferenc and Nádasdy Ferenc, Judge of the Country in the autumn of 1663. They accepted Zrínyi as the chief commander of the army in Hungary. According to this, Zrínyi assembled the Trans Danubian Region’s troops on 17 September in Vat. In October, he led the army to victory and defeated the Ottoman army at Vízvár in Upper Hungary. Then, he and his brother Péter gained a victory over the enemy at New Zrínyi Castle at the end of November.

As a preparation for the new Ottoman onslaught due the next year, German troops were recruited from the Holy Roman Empire and aid was also called from France, Zrínyi, under the overall command of the Italian Montecuccoli, leader of the Imperial army, was named commander-in-chief of the Hungarian army. Read what Zrínyi wrote to Montecuccoli in 1661:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/zrinyis-reply-to-montecuccoli-1661/

In 1664, Zrínyi set out to destroy the strongly fortified Suleiman Bridge of Eszék (Osijek). Destruction of the bridge would cut off the retreat of the Ottoman Army and make any Turkish reinforcement impossible for several months. Zrínyi advanced 240 kilometers in winter, on enemy territory and destroyed the bridge on 1 February 1664. He also took back several castles but he was frustrated by the refusal of the Imperial generals to co-operate. Yet, Zrinyi was internationally praised, received the Golden Fleece, and was honored equally by the Pope King Louis XIV of France, and King Philip IV of Spain.

The court remained suspicious of Zrínyi all the way, regarding him as a promoter of Hungarian separatist ideas. Zrínyi’s siege of Kanizsa castle, the most important Ottoman fortress in Southern Hungary, failed, as the beginning of the siege was seriously delayed by the machinations of the overly jealous Montecuccoli. Later the Emperor’s military commanders, unwilling to combat the Grand Vizier’s army hastily coming to the aid of Kanizsa, retreated. You can read more details about this campaign here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/1541-1699/the-famous-winter-campaign-of-zrinyi-1664/

The Emperor took away the command from Zrínyi who got hurt and returned to Csáktornya castle. Then, the Ottomans, ultimately, were stopped in the Battle of Saint Gotthard (1664). The Turkish defeat could have offered an opportunity for Hungary to be liberated from the sultan’s yoke. However, the Habsburg Court chose not to push its advantage to save its strength for the future conflict that would be known as the War of the Spanish Succession.

So the infamous Peace of Vasvár, the peace with the Turks, was negotiated by Zrínyi’s adversary, Montecuccoli. Zrínyi ran to Vienna to protest against the treaty, but he was ignored; he left the city in disgust. The peace treaty laid down unfavorable terms for the Hungarians, not only giving up recent conquests but also offering a tribute to the Turks, even though Austrian-Hungarian troops were the stronger.

It is still argued that he, despite being a loyal supporter of the court before, participated in the conspiracy which later became known as the Wesselényi conspiracy for the independent Kingdom of Hungary. However, on November 18, he was killed in a hunting accident by a wounded wild boar. Until this day, legend maintains that he was killed at the order of the Habsburg Court and “that boar spoke German”. No conclusive evidence has ever been found to support this claim; however, it remains true that the Habsburgs lost their mightiest adversary with his death. You can read more about his death here:

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts:

Please, support my work with a cup of coffee here:

or:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: http://Become a Patron!