The Battle of Várna 1444

The events leading to the Battle of Várna; the spring and the summer of 1444

Later generations said that the young King Ulászló I (also known as Wladyslaw III), monarch of Hungary and Poland, lost his life in the Battle of Várna in November 1444 because he broke the oath he had made with Sultan Murad. We have been talking about the glorious Long Campaign of Hunyadi, which ended in February 1444 and preceded the Battle of Várna. You can read about it here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/1372-1490/hunyadis-long-campaign-in-1443-44/

Let us take a closer look at the events leading up to the Battle of Várna, which Hunyadi won but the king lost by being killed in an unnecessary charge at the end of the battle. Let us look at the circumstances of the king’s oath and find out whether it was a reasonable one or not before we judge him too harshly.

Pope Eugenius IV had high hopes for the possible reunification of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches, and Emperor Johannes VII of Byzantium would have agreed in the event of a victorious campaign against the Ottoman Turks. Cardinal Cesarini, the Pope’s legate in Hungary, did his best to persuade the Hungarian-Polish king to go on the next crusade. As a result, King Ulászló swore in the spring that he would lead a campaign against the Ottomans in the summer. However, the plan was not supported by his Polish subjects, who felt that a new war was unnecessary. They were angry about the money they would have to pay and said that Poland was not in immediate danger.

Meanwhile, Sultan Murad was not idle. He began negotiations with his father-in-law, the Serbian despot Brankovics György alias Đurađ Branković. He agreed to give Serbia back to him and return his two sons, who had been blinded while in Ottoman captivity.

Brankovics tried to persuade Hunyadi János to help him bring peace between the Hungarian king and Murad. In exchange for Hunyadi’s help, Brankovics offered him his extensive lands in the Kingdom of Hungary. Not for nothing, Hunyadi was inclined to accept. Murad also offered to pay Ulászló 100,000 gold forints as compensation. The Sultan also promised him 25,000 Ottoman auxiliaries in case Ulászló decided to go on a campaign outside his empire. The truce was to last ten years.

Of course, the king received reports about the unstable situation in the Ottoman Empire, that there were uprisings, and that usurpers were rising up against the Sultan. There was great unrest in Edirne and bloodshed almost every day. The Turkish soldiers also revolted because their pay had not arrived. It also became clear that Murad had to move his army to Anatolia.

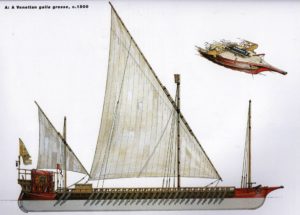

Who supported Cesarini’s warmongering? The ambassadors of Venice and Burgundy solemnly swore that their combined fleet would block the waters of the Helléspontos to stop Murad’s army coming from Anatolia. In addition, Cardinal Francesco Condulmar, cousin of Pope Eugenius, announced on 4 June that eight warships of the Papal State were ready in the harbor of Venice. In addition, the Burgundians were said to have equipped three more galleons and smaller ships in Nice. The cardinal appointed Walerand de Wavrin as admiral of the Christian fleet, but the cardinal remained the supreme commander.

At the same time, the Doge of Venice wrote to the Hungarian king that the ships were already on their way to Gallipoli and that more were being sent to the lower Danube to help the Christian army cross. The last reason given by Cesarini was that the Ottomans had not kept the peace by not surrendering the castle of Galambóc/Golubac within eight days. On the advice of Giuliano Cesarini, the Hungarian king decided to take another oath before signing the armistice. In this oath, taken at the castle of Szeged, he swore that the preparations for the new campaign would not stop and that the truce with the Turks would not be valid.

As it happened, the Sultan’s offer of peace was signed by Hunyadi on the king’s behalf in Nagyvárad (Oradea) in August. Cardinal Cesarini then absolved the king of the “oath he had sworn to the pagans”.

In the event of a successful campaign, the king promised to make Hunyadi king of Bulgaria. Nevertheless, Hunyadi managed to take over the vast lands of the Brankovics in Hungary. The Sultan also took steps to fulfill the terms of the armistice. However, on 22 September the campaign began and the Hungarian troops set out to liberate the Balkans. Their conditions, though, were far worse than at the start of the Long Campaign a year earlier.

Who were the real oathbreakers?

Hunyadi János crossed the Danube with his own troops at Orsova on 22 September 1444. King Ulászló I, alias Wladyslaw III, later joined him with his Polish and Hungarian soldiers. As for the truce they broke, it was clear from the start that Sultan Murad had no chance of fulfilling the Hungarian king’s terms. The Albanian Skander Bey offered to help Hunyadi and his letter soon arrived in the king’s camp. He wrote:

“Who would not take up arms and rush into open danger for the people of Hungary, who have defended Christendom for so long by fighting and shedding their precious blood? By birth, they are the enemies of our eternal enemy…”.

Despot Đurađ (György) Brankovics

However, the Albanian troops could never join the army because this time the despot Brankovics did his best to separate them from the Hungarian and Polish crusaders. Skander Bey’s 15,000 men could never join the Crusaders. Having got what he wanted from Murad (his Serbian lands and the return of his two blinded sons), Brankovics no longer supported Hunyadi. In terms of the campaign, this was to prove decisive.

When they reached Nicopolis (Nikápoly) on 19 October, they were joined by the soldiers of the Wallachian Voivode Vlad II and some Bulgarian troops. However, the total number of Crusaders did not exceed 20,000. They could not take the inner castle of Nicopolis, only the city. Voivode Vlad Dracul was astonished to see how small the Hungarian king’s army was.

They were marching around the country of Brankovics as he didn’t let them go through. This time they followed the Danube River, not crossing the passes of the Balkan mountains as they had tried last year during the Long Campaign, led by Brankovics. After a five-day march, the Christians reached the castle of Vidin, which they besieged. It fell after six days.

The Byzantine Emperor

Little did they know that the Burgundian, Papal, Genoese, and Venetian fleets had only 21 ships, not enough to blockade the waters of the Bosphorus and the Hellespontos. Originally, more than 30 ships had been promised.

The Hellespontos is 80km long and 6km wide at some points. The commander of the Christian fleet, Admiral Wavrin, finally realized that his mission was impossible and sent a message to Constantinapolis asking the Byzantinians to help and stop Grand Vizier Halil from transporting Murad’s army to the European coast. Unfortunately, the emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, didn’t give a straight answer and did nothing. The Orthodox were not interested in helping Rome. How could he, when he had invaded the Latin Duchy of Athens that summer?

A few days later, Grand Vizier Halil managed to take control of the European side of the Bosphorus and the Hellespontos. He hired cannons from the Genovians. Meanwhile, the Anatolian army arrived and began to bombard the ships from the other side as well. The Christian ships had to stay in the middle and fight against the strong current.

The Genovese

The Genoese ships clearly betrayed the Crusaders. They made a deal with Murad, helping him to transport his army to the European side. For two days and two nights, they carried the bulk of the Anatolian army to the other side, receiving one gold florin per soldier. They collected 49,774 pieces of gold in exchange for their labor, including the cannons they rented. They would have received two thousand more if they had prevented the Christian fleet from sailing into the Black Sea, but this proved unnecessary.

Back home in Genoa, they donated this sum to the construction of the Cathedral of San Lorenzo:

The Crusaders are reaching Várna

From Nicopolis, the Christian army marched towards the sea. Between 24 October and 9 November, they took Yenibazar, Sistov, Razgrad, and Provádia, and then the Ottoman garrisons of Kavarna, Makropolisz, Galata, and Várna surrendered.

Sultan Murad arrived in Provadia with a reinforced army, blocking the Crusaders’ way home. Thus the Hungarian/Polish/Bulgarian and Wallachian troops camped at Várna on 9 November, betrayed by both the Byzantine Emperor and their Christian Genoese allies, not to mention the role of the Serbian despot Brankovics. I don’t know if Hunyadi or the king had any idea of the danger they were walking into.

Could the situation have been worse?

The Battle of Várna

The Battle of Várna seemed to have been decided before it began: the Genoese ships transported Sultan Murad’s army across the Bosphorus, allegedly in exchange for one gold piece per soldier. Not that the other Christian ships had made much of an effort, not to mention that there were only half as many of them as the Pope had promised to send. According to hearsay, they remained passive because they too had been bribed.

However, the fact remains that if the Western and Byzantine forces had stuck to the original plan, the European part of the Ottoman army could have been defeated by this relatively small Crusader army.

Until then, the Crusaders had not encountered any major Ottoman force. Now, on 10 November 1444, they found the main body of the Ottoman army camped barely 4km north of them, blocking their way home.

In the morning, the military leaders were divided, and many recommended withdrawing to the south to avoid the Ottoman army. Cardinal Cesarini, who had persuaded the king to launch the campaign by telling him that an oath given to the pagans was not a valid commitment, now wanted to wait for Christian reinforcements from the ships. He would have surrounded the army with a wagon-burg (a fortified camp surrounded by wagons). He obviously didn’t know that there would be no such Christian army coming from the sea.

Finally, it was Hunyadi who saw only one possible solution: they had to attack the Turks at once if they wanted to survive. He suggested that they cut off the wings of the enemy and then turn on the Janissaries. He added: “Escape is impossible and surrender is unthinkable. Let us fight with courage and honor.” They took his advice.

But it all began with bad omens. The king’s page accidentally dropped the king’s helmet, which got a dent. Then Ulászló, dressed in full armor, mounted his horse, but the animal bolted and kicked him, bending the shoulder piece of his armor. The horse became so wild that it had to be replaced.

The next bad omen came when the army was deployed and the standard bearer was appointed. The flag of the kingdom was given to the 60-year-old Bátori István, the judge of the country, and the father-in-law of Lord Szilágyi Mihály. According to the old Hungarian military custom, his spurs were taken away. King Ulászló approached him and asked him if he was ready to carry the flag decorated with the cross of Saint George. At that moment the wind broke the mast of the flag in two. It immediately fell to the ground.

Hunyadi positioned his army to face north. On his left he was protected by the Devnya Lake and its marshes. His left wing stood at the lake, led by Szilágyi Mihály, Hunyadi’s brother-in-law. The main force was led by the king himself, while Tallóci Frank, Bán (Duke) of Croatia led the right wing. The slightly curved battle line was supported by the wagon fort behind the right wing, where the cannons were placed. The wagons were guarded by Čejka Herman’s experienced Bohemian mercenaries.

In Szilágyi’s left wing there were about 4,000 mercenaries and Transylvanian soldiers, together with men from the Temes region, led by Orros György. As for Tallóci, he had the armed men of the bishops and the Polish auxiliaries under his command. There were five episcopal units, the fifth led by Cardinal Cesarini himself. The troops of Bishop Dominis János of Várad remained in reserve.

King Ulászló was surrounded by 3,500 Hungarian and Polish knights and royal troops. Hunyadi was detached from them to lead his contingent of Wallachian troops wherever he thought they were needed. At first, they stood behind the king’s troops.

Sultan Murad chose an elevated position from which he could overlook the entire battle. His logistics unit immediately dug trenches around him. They herded 500 camels around the trenches, loaded with sacks of money, expensive textiles and silk. The janissaries were to cut up the sacks in case the Christians approached the Sultan. They trusted that the greed of the mercenaries would buy time for the Murad to escape.

The Ottoman battle line followed the Crusader line in a semicircle. The Rumelian troops stood on the right wing, while the Sultan deployed the main force a little behind them. On the left wing were the Anatolian soldiers of Bey Karadzsa, nearly 30,000 men. Further to the left were the Asab and Akinji soldiers, whose task was to launch a mock attack on the Hungarian right wing to lure them out of their position.

The battle began on the morning of 10 November 1444 and lasted until the evening. The Asab and Akindji soldiers, 10-13,000 men, attacked the Hungarian right-wing around 9 a.m. At this point, the 10,000 Janissaries, the elite defense force, hadn’t yet joined the fray; they were still standing in their square formation.

Bán (Duke) Tallóci repulsed the attack on the right wing and began to chase the Turks headlong. He was followed by the troops of Rozgonyi Simon, Bishop of Eger, and the men of Dominis János, Bishop of Várad. They were lured out and the 10,000 Rumelian Sipahi horsemen, led by Pasha Daud, attacked them. The bishops and Cesarini’s men were frightened and retreated towards the sea. The aforementioned bishops and Cardinal Cesarini were killed, but Tallóci’s soldiers managed to get into the wagons. In this way, the right wing of the Crusaders was almost wiped out in the morning. Rumour has it that Cesarini was killed by the Hungarians, who wanted to take revenge for his advice.

Fortunately, Hunyadi’s 3,000 heavy cavalry came to their rescue. They drove back the Sipahis and killed Bey Karadzsa. The Wallachian troops then attacked the Ottoman camp and plundered it. On the way back, Hunyadi’s horsemen ran to help the king’s troops, who were wavering. The Ottomans tried to trap the Hungarians on the other side as well, but they could not outwit Lord Szilágyi. On the contrary, it was Lord Szilágyi, leading the Székelys and the Transylvanians, who was able to surprise them. He attacked the enemy and they cut them down for four hours. They finally got tired, but the Sipahi riders finally fled.

All in all, Hunyadi’s original plan seemed to have worked. All the Ottomans had left were the Janissary regiments and the 10,000 horsemen of Seháb ed Dihn. It was almost dusk when 5,000 Christian horsemen attacked and routed the remaining Ottoman cavalry. The Crusaders even gave chase. In effect, the battle was won against an enemy twice as strong. Some of the Ottoman cavalry fled as far as Edirne.

It was at this point that disaster struck. Seeing the Turks retreating, the king wanted his share of the glory. King Ulászló and his 500 Hungarian-Polish knights charged the janissary camp, which was also protected by sharpened stakes. They held out for a while, then opened up and swallowed the king and his men. A few moments later, the king’s horse bolted and threw him to the ground. It was a janissary called Khodzsa Hizir who beheaded the young king of Hungary and Poland. It was the first time in Hungarian history that a Hungarian king was killed in battle.

The head of Ulászló was put on a spear and carried around for all to see, then taken to the Sultan. Seeing this, the Turkish right wing returned and the Crusaders left the battlefield. Then Hunyadi tried to save what he could and organized the retreat. However, he was unable to save the defenders of Wagonburg, whose soldiers fought until the next morning and died on the spot. However, some of them managed to escape and return home.

Hunyadi took the remnants of the army home, they mourned the loss of the king and the cardinal, Tallóci, Rozgonyi along with the death of 10-12,000 men. However, the Ottomans lost about 20,000 soldiers. According to Jókai Mór, Sultan Murad said: “I would wish such a bloody victory to no one but my enemy”.

Let us pay tribute to the Hungarian, Polish, Walachian, Saxon, and Bohemian heroes, and let us not forget those who caused their downfall by letting the Ottomans cross the Bosphorus.

It is true that Murad was not strong enough to pursue the retreating Crusaders. The Ottoman army moved into southern Greece. For some reason, Vlad Dracul, the Wallachian voivode, captured Hunyadi but released him when the Hungarian palatine Hédervári threatened him with war. Vlad then personally escorted Hunyadi to Brassó (Brasov). At home, Hunyadi faced anarchy after the death of the king, and he was the only person strong enough to bring order to the country. No wonder he soon became governor of Hungary.

I can make this content available only through small donations. If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here: [wpedon id=”9140″ align=”center”]

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!