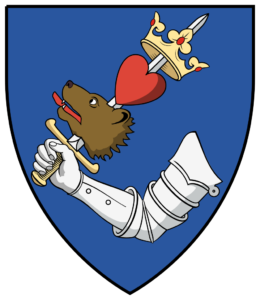

Marosvásárhely

Marosvásárhely (Târgu Mureș, Nai Muark) is the center of the Hungarian Székely people of Transylvania, it is in Romania. Marosvásárhely is situated in the central part of the Transylvanian Basin, on a varied terrain, on the edge of the Székely Land, at the junction of the hills of the Mezőség Region and Küküllő Rivers’ Region. Marosvásárhely is about 100 kilometers from Kolozsvár (Cluj, Klausenburg), 130 kilometers from Nagyszeben (Sibiu, Hermannstadt), 173 kilometers from Brassó (Brasov, Kronstadt), 346 kilometers from Bucharest, and 510 kilometers from Budapest.

Thanks to its favourable location, it offered the right conditions for human settlement. The oldest finds date back to the Polished Stone Age (6th-4th millennium BC), but there are also scattered finds from the Roman period, and in recent years continuous archaeological excavations have uncovered finds from the Migration Period and the Árpád period. Archaeologists and local historians date the origins of the town to around the 11th-13th centuries, followed by a continuous historical development that has continued since then.

The Renaissance castle is still intact, it is around the central church of the town, on the left bank of the Maros River. It used to be a quite big city in medieval times, the present outlook of the buildings reflects the mid-17th century style. The ten-meter-high walls enclose an area of 230 x 190 meters. Each bastion of the wall belonged to a particular medieval guild whose members were responsible for defending it. There was a single entrance to the castle, it was opening towards the settlement. This gate was protected by a deep moat and a drawbridge. The Maros River was feeding the moat with water.

As we mentioned, the first settlement was born in the 11th century but we know that its Gothic church was built in 1260 by the Franciscan monks. (The Dominicans’ church had been destroyed by the Mongols in 1241.) For better defense, the castle is protected by the church with a double wall. As for the town, it was first mentioned in writing only in 1323 as Novum Forum Siculorum. It was an agricultural town in the 15th century. The bell tower was built around 1440, later loopholes were cut in its wall.

The first judicial privilege was given to the town by King Matthias Corvinus in 1470 and a market right in 1482. Contemporary documents show that the weekly market was held on a Thursday, and the dates of the national fairs were Lord’s Day (the Thursday of the second week after Pentecost), St Martin’s Day (11 November) and Flower Sunday (the Sunday before Easter).

Marosvásárhely (it means “Maros-market-place”) had been the host of 39 Diets since 1439. In the settlement, which was known and organized as a fairground, local craftsmen and artisans settled alongside the merchants and, as their numbers grew, they formed guilds. The first craftsmen to form guilds were butchers, sewers, and tailors, with the first known guild charter being that of the butchers in 1493.

Voivode Báthory István reinforced its castle in 1492 with towers because he wanted to keep a strong garrison there against the restless Székely people who were always ready to rebel when their ancient rights and liberties were threatened by the Hungarian king or by the Transylvanian princes. They were well-armed border guards, for example, they defeated the army of General Tomori Pál next to the city in 1506. (Note, that for educational reasons I am intentionally using the Oriental name order for Hungarians where family names come first.)

You can read more about the Hungarian Székelys (also: Szeklers) here:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/who-were-the-szekelys/

We know that the church was taken away from the Franciscans at the time of the Reformation. Bloody years came during the reign of Prince Báthori Zsigmond. The mercenaries of General Basta burned and looted the town in 1601. The surviving inhabitants, led by the town’s Chief Judge Borsos Tamás, fled to Brassó (Brasov, Kronstadt) to seek shelter. Sadly, the town was put on fire again the next year, this time Németh Gergely gave the order. Allegedly, Chief Judge Borsos saw the formidable walls of Brassó, and later they tried to build similar walls around Marosváráshely, too. Interestingly enough, General Basta also supported this idea.

Székely Mózes, the only one Székely who was Prince of Transylvania, visited the city in 1603 when he liberated Transylvania from the enemy. At the beginning of the 17th century, the monastery, in a state of ruin, offered little protection to the inhabitants who had sought refuge there. They had to build a fort, and the rebuilding of the castle lasted until 1653. It was the time when the Gothic windows of the church were walled in and turned into narrow loopholes. The school building’s gate was also walled in and two more towers were built there.

One more drawbridge was constructed right at the gate of the church. Prince Bethlen Gábor made it a free royal city on 29 April 1616 when the major of the town was Borsos Tamás. Before this date, the city had been known as Székelyújvásárhely or Székelyvásárhely but we also know the names as Vásárhely, Újszékelyvasár, Újvásár. From this time on, the settlement was called Marosvásárhely. We know that the reconstruction work was going on in 1620 and 1630 as well. Thanks to these efforts, only the town was burned in 1658 by Wallachian and Ottoman raiders and the Székely people could survive behind the walls.

Marosvásárhely fell to the Ottomans in 1661, it was Pasha Ali who took the town and made Apafi Mihály the Prince of Transylvania among its walls in that year. The famous Turkish traveler, Evliya Celebi was with the Ottoman army and he described the castle like this: “It is an old castle, with just one strong gate that is facing towards the west. The castle has five strong bastions that were built of concrete. But the fort is small and its moat is shallow.

It has churches with nice towers and there are strong houses with plank roofs and nicely decorated streets with wealthy inhabitants. To the West, there is an outer town that is 10,000 steps wide. It has no walls around it, just a deep moat with a gate and a wooden bridge.” It is too bad that due to the Ottomans’ carelessness, the city burned down next year again.

The fortification provided security against raiding troops, and the town survived the Crimean Tatar invasion of 1658-1661 without losses but would have been defensible against a larger army for a short time. However, the next raiders and looters were the Austrians in 1687. Later these activities were repeated. Let us not forget that Rákóczi Ferenc was made Prince of Transylvania in Marosvásárhely on 5 April 1707, the ceremony was conducted by Thelekessy István, Bishop of Eger. After the Rákóczi War of Independence, the civilian population was evicted from the castle and the walled area of about 3.5 hectares was converted into a military fortress. During the first part of the eighteenth century, this city was hit four times by devastating plagues. Despite these hardships, the city remained the cultural, educational, and trade center of the Székely people.

The transfer of the Royal Table to Marosvásárhely in 1754 greatly helped the slow development of the town, which had been going through hard times. Its officials, subordinates, and their families had a positive influence on the economic and cultural life of the town. The Reformed school, founded in 1557, later developed into a college by taking in students and teachers from Sárospatak, which also gave the town an educational role. The college, built at the end of the 18th century, can still be seen today, with the Art Nouveau part of the building added at the beginning of the 20th century. The Teleki Téka, founded in 1797 by Count Teleki Sámuel, Chancellor of Transylvania, is one of the city’s most important cultural monuments.

After the turn of the century, Aranka György, the language innovator, Teleki Sámuel, the founder of the library, Bólyai János, the uncrowned prince of Hungarian mathematics, and his father, the polyhistor Bólyai Farkas, the teacher, lived within its walls for more or less long periods. It was in this period, 1820-22, that the musical fountain was built by the legendary craftsman Bodor Péter, which delighted visitors with music until 1836 and with fresh water until its demolition in 1911 (a copy of the fountain, made in 1936, can be seen on Margaret Island in Budapest).

The events of the 1848-49 War of Independence were decisive for the town and its people, and their stories, myths and memories have been passed down from generation to generation. The monument to the Székely Martyrs erected in 1875, which still stands today and serves as a traditional place of celebration, is evidence of this, while numerous statues (Bem, Kossuth, Széchenyi, Petőfi), street names and commemorative plaques, which no longer exist, have also preserved the memory of the War of Independence.

The last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century, the so-called “Bernédy era”, was certainly the most decisive period in the development of the town, the results of which still determine the layout and specific image of the center of Marosvásárhely. Built on the initiative of Mayor Bernédy György, the buildings, mostly in the Art Nouveau style, still determine the urban structure and the specific image of the center of Marosvásárhely. (The most spectacular ones are the Palace of Culture, which can still be visited, the former Town Hall, now the County Hall, the former Pension Palace and the former Military Secondary School, now the George Emil Palade Medical, Pharmaceutical, Scientific and Technological University).

The poet Ady Endre wrote: “An important Transylvanian town has built a palace of culture, strange and great, thanks to a particularly great man. – It will be, if Fate wills it, a Hungarian refuge, rich and covering. Here we Hungarians, who have sinned so much against each other, will guard ourselves. Here we will gather with poetry, music, speech, in case of trouble.” In addition, the modernization process under Bernády’s mayoralty has put the city on the path of infrastructural development. The momentum of construction was stalled by the heavy loans, but most of all by the events of the First World War. On 2 December 1918, the Romanian army invaded the town, which at the time had just over 30,000 inhabitants.

The period between the two world wars was largely characterized by the symbolic occupation of space as a process of integration in Romania, which was also reflected in the replacement of most of the public squares, street names, and monuments, and the construction of two new Romanian cathedrals in the main square. Although censuses show that the Hungarian population of the city accounted for three-quarters of the total population during this period, it was only between 1926 and 1929 that the city had a Hungarian mayor.

Photo: Rsocol

The period after the Second World War saw the greatest structural and demographic changes in the city. With the 1952 constitutional amendment, the city became the center of the Hungarian Autonomous Region. Despite its name, the Hungarian Autonomous Region had no real economic and political autonomy. It was created for the Hungarian community living in the region, with rights in terms of language and cultural life, and as such it functioned as a kind of “cultural glasshouse” in socialist Romania.

The situation of the early 1960s was practically preserved by the administrative “reform” of 1968, which finally abolished the Hungarian Autonomous Region and created Mures County in its present administrative form. At the same time, forced urbanization and economic investment led to the construction of new housing estates, which, with the influx of new Romanian residents, largely changed the ethnic character of the city, but also affected everyday life, turning the city into a “frontline city” by the time of the regime change. This essentially meant that, despite everyday interactions, the Romanian and Hungarian populations formed a parallel community, with the potential for ethnic conflict.

Although the events of late December 1989, in many cases euphoric, held out the possibility of a period of social and interethnic reconciliation with the fall of the dictatorship, the events of the “Black March” in Marosvásárhely (17-21 March 1990) set back the possibility of this for years. The inter-ethnic conflict in the city, which had many of the characteristics of a pogrom, had serious consequences: five people were killed, hundreds were wounded and there was a wave of emigration as a result of the events. The aftershocks of the event also affected the political scene in the city but were also difficult to overcome for the Hungarian and Romanian communities, which lived side by side in roughly equal numbers.

Formerly known as Székely-Vásárhely and long considered the capital of the Hungarian Székely nation or ‘City of Flowers’, it is still the largest city in Romania in terms of the Hungarian population and the 16th largest in terms of total population.

Enjoy the video about the castle:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vtZu_c2Mj9Q

Source: partly from Fodor János https://rubiconintezet.hu/project/marosvasarhely-a-szekelyek-fovarosa/

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital, they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Here are more pictures of Marosvásárhely: