He was the American hero who defended the National Museum with a whip.

On May 11, 1925, American General Harry Hill Bandholtz died, a man who made Hungarian history when armed only with his riding whip (later donated to the Hungarian National Museum at the request of then Prime Minister Huszár Károly), he prevented a group of Romanian soldiers from looting exhibits from the National Museum.

Romanian lorries were already lined up in front of the National Museum waiting to be loaded; the only thing that saved the museum from being looted was that Bandholtz had the Romanian soldiers locked out and the doors sealed on behalf of the Allies.

Foreword – the chaos

Now, we don’t talk about how the events unfolded and how Károlyi Mihály seized power. We have to say a few words about Archduke Habsburg Joseph because he was the one who dealt with the American general. The Archduke fought heroically in the First World War and was one of the few generals of his time (and here we are not thinking primarily of the monarchy’s general officers, but of all the belligerent parties!) who led their troops well and looked after their subordinates.

It is no accident that he became a popular figure in Hungarian public life. In October 1918, he briefly served as the king’s representative with full powers – homo regius – trying to resolve the revolutionary situation in Budapest, which was unfolding and tending towards a coup, but after the appointment of Károlyi Mihály he was ‘forgotten’ and found no public role for himself.

Yet he was preparing for armed defence, and since he had a good reputation among the soldiers, he could probably have even put the collapsed, over-politicised and rebellious army in order. However, as he was neither called upon to do so nor saw any opportunity, he retired to his estate in Alcsút. Then, the communist terror government took over control in Hungary. The communists didn’t dare to arrest him but kept him under close surveillance.

Thus, on 6 August 1919, with the consent of the Italian part of the Entente mission and the support of the Romanian military authorities, and with the help of a small gendarmerie detachment, Friedrich István drove out the trade unionist (one might say post-communist) government meeting in the Alexander Palace in Buda. The next day, Archduke Joseph stepped in and charged Frederick with forming a government, while declaring himself governor of Hungary. Just four days later, however, he received an ultimatum from the Romanians occupying Budapest.

The Romanian army in Budapest

The Archduke gained power only three days before the Romanian troops’ arrival. 3 August 1919 is a black day in Hungarian history. It was the day when Romanian General Rusescu took Budapest with three companies of soldiers – some 400 men – and kept it ‘occupied’ until the arrival of the main Romanian forces the next day.

The Romanians still refer to this glorious warlord as the first army in the world to liberate a state from the reign of communism. In August 1919, the Soviet Republic fell. The majority of the nation did not regret this at all, considering this short reign of communist terror too long. What was more disheartening, however, was the fact that Béla Kun – despite their loud promises – was unable to defend the country against invading Romanian troops.

However, the invasion of Hungary took place against the orders of the Supreme Council of the League of Nations. Therefore, French President Clemenceau – quite logically – called on the Hungarians to observe the armistice:

“Hungary must comply with the terms of the armistice and respect the borders established by the Supreme Council, and we will protect you from the Romanians, who have received no mandate from us. We will immediately send an allied military mission to supervise the disarmament and ensure that Romanian troops withdraw.”

The members of the Allied Military Mission were Generals Harry Hill Bandholtz (American), Reginald Gorton (British), Jean César Graziani (French), and Ernesto Mombelli (Italian). They were tasked with overseeing the departure of Romanian units from Budapest, Hungary.

Hungarian-Romanian Personal Union?

On the very first day of his stay in Hungary, General Bandholtz was visited by Archduke Joseph, who, driven by personal ambition but trusting no one, tried to play the role of “governor” and presented him with the Romanians’ ultimatum, according to which Hungary would have to meet all the Romanian demands, hand over all its military equipment and supplies, and enter into a political union with Romania, in which the Romanian king would rule Hungary along the lines of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

According to the demand, Hungary should have handed over all its war material and also joined Romania in the war, so that together they could take the whole of Banat from the Serbs. Of course, the question is, how could Hungary, if it had surrendered all its war material, have opposed anyone? In the concept, the Romanians also made it clear that Romania and Hungary would enter into a personal union under the crown of the Romanian King Ferdinand. The areas around Makó and Békéscsaba would be handed over to Romania. In return, Romania promised educational concessions, including “a Hungarian university maintained or at least subsidised by the state”.

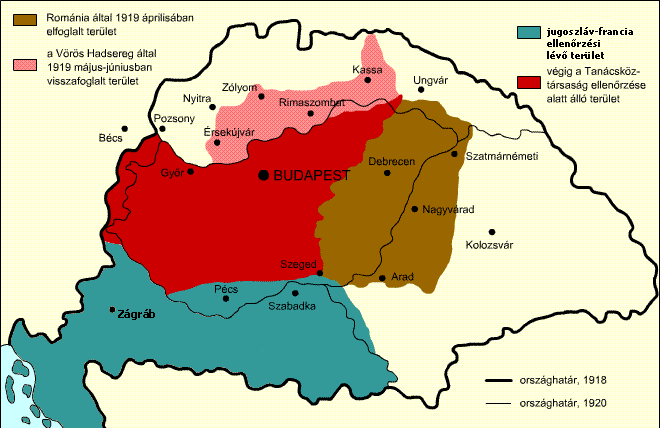

Dots: The border of Hungary in 1914; Line: The borders after Trianon; Blue: Czech demands with the “Slavic Corridor” (Masaryk, 1915); Purple: Romanian demands (according to the Treaty of Bucharest in 1916); Green: South Slav demands (by the South Slav Committee of London); Orange: the remaining and undemanded territory of Hungary;

On territorial issues, Romania would have supported the Danube-Drava line as a Serbian-Hungarian border, which at that time seemed questionable, since there were Serbian occupiers in Pécs and Baranya, not to mention the South. According to the Romanian plan, the Hungarians would have to retake Bácska, Pécs, Baja, and the Drávaköz, of course, with weapons. The strategic goal was a Romanian-Hungarian-Italian alliance against Yugoslavia and the Soviets. Hungary would be given some credit and perhaps be less plundered; the latter was a burning issue at the moment.

In its desperation, the Hungarian government was willing to negotiate. Some believe that a Romanian-Hungarian alliance could have been a solution to the Transylvanian issue, but this is precisely the point where Romania offered practically nothing. Romanian politicians in Transylvania might have been willing to make concessions, but not Bucharest. On top of that, there was the complete lack of Hungarian confidence in Romanian promises, and the British Empire and the United States were strongly opposed to the Italian-Romanian plans.

Hungary would have jumped into another war in the service of Romanian interests, with only one guaranteed outcome: the loss of Makó and Békéscsaba. Brătianu considered the acquisition of these two cities necessary, if only because of the Arad-Nagyvárad (Oradea) railway line, which then ran through Békéscsaba. In geopolitical terms, a real line of defence against the Soviet Union could only have been formed by a strong Hungarian-Polish-Romanian alliance.

Romania, like Czechoslovakia, would pay a heavy price for the complete alienation of Hungary two years after Munich, in 1940, when it would be caught in a Soviet-Hungarian claw. But even if the alliance had been realized at that time, it would have been very unequal and of doubtful durability because of Romanian insatiability. As Raffay Ernő writes: “Hungary (…) would have had a subordinate role, for example in the shaping of its foreign policy.”

On 19 August 1919, the Romanians proposed that the so-called “empty” Hungarian throne be replaced by a Romanian royal prince. The action against Serbia would have been maintained, but the Romanians wanted recognition of the Tisza River border (!) in return. Thankfully, this did not come to anything either.

So, the Romanian ultimatum was about disabling Hungary for a long time. In this plan, Hungary, seen as the main rival, which Romania wanted to replace as the dominant state in south-eastern Europe, was essentially to be one of Bucharest’s distant outposts.

This idea was not conducive to Hungarian-Romanian historical reconciliation.

The role of General Bandholtz

After studying the document that contained the aforementioned conditions, General Bandholtz suggested this to Archduke Joseph:

“Because it was not the Romanian high commissioner who delivered it (the ultimatum), you can safely tell the sender to go straight to hell.”

With this statement alone, he would have written himself into Hungarian history, but his further actions only increased the sympathy of the Hungarian people for him. And this sympathy was mutual…

General Bandholtz arrived in our country in a completely unbiased manner, representing his country, but seeing the activities of the Romanian troops in Budapest, led by officers with rice-braided hair and wearing lipstick, his sympathies soon turned towards the Hungarians.

For example, the Romanians were about to remove 135 truckloads of equipment from the State Railway Works on 25 August, with a further 25 trucks still being loaded, when General Bandholtz intervened and prevented the works from being looted.

His most famous incident with the Romanians was at the National Museum. On 5 October 1919, Romanian lorries were already lined up in front of the museum, waiting to be loaded, to take away the art treasures from the Romanian territories (e.g., Transylvania) that they were “entitled” to. And, of course, whatever else caught their fancy… And he, according to legend, made his way through the Romanian soldiers to the museum on his horse, using his riding whip…

He also prevented the occupying Romanian troops from transporting the collections of the National Széchényi Library, which at that time belonged to the museum, to Romania as war booty.

In 1936, a grateful Hungarian nation erected a statue to the general, who died on May 11, 1925, in Constantine, Michigan. Although we were officially at war with the United States in World War II, the statue remained in place with the inscription in English:

“I simply carried out the instructions of my Government, as I understood them, as an officer and a gentleman of the United States Army.”

The statue was removed in the late 1940s under the pretext of restoration and lay in a statue cemetery until the late 1980s. At the request of Ambassador Salgo, it was then placed in the garden of the Ambassador’s residence in Zugliget. It was moved to its original location in Freedom Square in July 1989, just days before President Bush’s historic visit.

(Source: Szócsinné Vitéz Léber Ottilia, Ezerszínű Világ, and Huszárvágás Blog https://huszarvagasblog.hu/roman_magyar_perszonalunio.html)

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn