This was the first real field battle of the Rákóczi War of Independence (1703-1711), where the main armies compared their strengths. The Battle of Koroncó is one of the battles of the Rákóczi War of Independence, fought on 13 June 1704 between Koroncó and Győrszemere, on the banks of the Rába. Despite a fivefold superiority in numbers and good command and tactics, the battle was lost by the Kuruc army because their untrained and inexperienced cavalry did not carry out the orders of their officers.

In May 1704, Bercsényi Miklós sent General Forgách Simon, who had recently sided with the Kuruc (anti-Habsburg) forces, to Transdanubia, and he soon swore allegiance to Rákóczi. However, he considered his army insufficient against Heister, who had left Komárom and urged the commander-in-chief to send the army of Károlyi Sándor to him. This could be done only after the victory at Szomolány on May 28, when Károlyi was sent to the Transdanubian region with about 4,000 men.

However, he did not join Forgách but started a raid towards Austria and plundered the surroundings of Vienna. On the 9th, Heister camped near Győr, at Gyirmót, when Forgách approached him with his troops. He was preparing for a battle with the Imperial generals to prevent them from retreating to Vienna. This was prevented by Károlyi, who had arrived in Rábaköz in the meantime.

Although the Kuruc troops were numerically superior, consisting of about 18,000 men, the experienced combat infantry numbered only about 3,000 Hajdú soldiers. The majority of the army was made up of loosely disciplined, poorly trained, and equipped cavalrymen who had only recently joined under the banner of Rákóczi. The artillery consisted of only 6 cannons. The commander of the army, Forgách Simon, was a well-trained, highly experienced soldier who had not only received theoretical training during his 17 years of Imperial service but had also become well acquainted with the Austrians’ fighting style.

On the other hand, the Imperials had trained regular infantry. Under Heister, there were 1,600 infantry and 2,000 Serbian and Croatian cavalry. His 12 cannons, however, outnumbered those of the Kuruc. The right wing was commanded by Colonel Count Ranow, the left wing by Colonel de Viar,d and the artillery by Colonel Weiler.

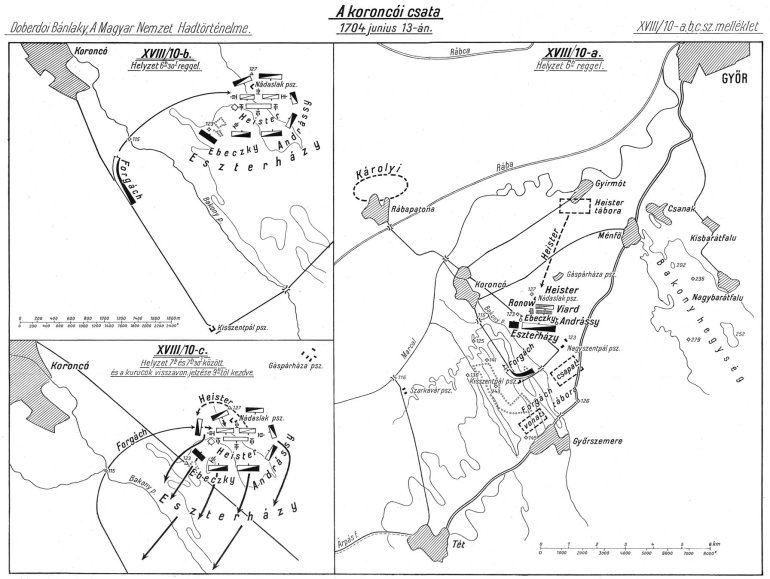

On June 12, Károlyi arrived on the left bank of the Rába, and Forgách hastened his crossing to catch Heister, who had formed his troops in battle formation during the night between two fires. Forgách, however, was not unprepared for him, and Heister was unable to take advantage of the element of surprise. The Kuruc general gathered his troops, entrusted the bulk of his 11,000-strong army to Esterházy Antal, and ordered him to attack from the front. He, with his 7,000 cavalry, was about to surround the Imperials from the west in the cover of a hill. Outnumbered by the Kuruc, their army could easily encircle the enemy, whose cannonade halted their advance.

The Imperials turned on the Kuruc on all sides, who stood their ground but dared not attack. The Austrians formed a square formation with two lines of battle, with infantry, cavalry, and artillery divided proportionally between them. On the flanks were the fast-moving Serbian cavalry. Ammunition carts were placed between the two lines. Heister, holding the square formation, moved his troops towards the Kuruc.

The first clashes took place on 13 June at around 5 am. At this time, Forgách still expected the approaching units to be Karolyi’s troops, so he rode out to greet them. However, the Serb hussars who were ahead of the Austrians opened fire on him.

By 7 a.m. Forgách’s cavalry had arrived, so the Kuruc cavalry on the left flank went on the offensive, pushing the Imperial line. Forgách then quickly put his army in battle order. He planned to surround the Imperial troops on the left with about 7,000 horsemen and then attack them in the rear. As this would take longer, Eszterházy and the rest of his army would slowly approach the enemy from the front and attack. On Eszterházy’s left flank were the units of Ebeczky István, on his right flank Baron Andrássy István.

However, there was an interesting moment when the charging general was not followed by his troops into the killing cannon fire but stopped on the top of the hill. On the right flank, Andrássy also took courage and attacked, but the rifle fire only confused the battle lines.

Since the Hungarian troops outnumbered the Austrians, their front line was much wider than the enemy’s, Eszterházy tried to encircle the flanks by turning the edges. Approaching the Imperial army about 300 metres away, their guns opened fire on the Hungarians, who returned fire with cannons mounted on a nearby hill, but could only threaten the Imperial right flank. During the artillery duel, which lasted about 1.5 hours, the Hungarian infantry took cover on a hill. Both the Hungarian participants and the Austrian reports emphasise that the unaccustomed Kuruc troops held their own in this “destructive, murderous cannon fire”.

Around 7 o’clock, Forgách’s encircling operation reached its goal. Sensing this, Ebeczky attacked on the Hungarian left flank, but only managed to push back the Serbian Hussars, and could not break through the imperial front line, so a gun battle took place. This was followed by a rush of 7,000 horsemen led by Forgách himself from a hill, but the Austrian cannon and rifle fire prevented the soldiers from following their leader. Seeing Forgách’s attack, Eszterházy’s and Andrássy’s units also charged the Imperial troops, but their rifle fire stopped the action here too.

With the momentum broken, the Hungarian lines were also broken up, and Heister recognised the gap that had opened up. He sent Schlick’s dragoon regiment, under Colonel Stadlmayr, to flank Forgách’s cavalry. Heister himself joined the charge. This turned the tide of the battle, as first on the left flank and then elsewhere, the Hungarian hussars fled. Despite the personal courage and orders of the Kuruc officers, more and more troops began to flee. First, the left flank was broken up, then the cavalry.

The disintegrating Kuruc army fled toward Tét, Mórichida. The remaining infantry fought for another half an hour, retreating 2-3 km, but soon they too were scattered in a hopeless situation. Those who fled into the woods suffered minor losses, while those who ran towards the Rába bridge at Árpás suffered greater losses due to the 10-11 hour pursuit of the Imperial cavalry. Many Kuruc lost their lives in the swamps along the river. At the time of the battle, Károlyi’s army was in nearby Rábapatona. The Hungarian cavalry had a better chance of surviving the battle, but the infantry was shattered.

He did not intervene in the clash, even though he could have brought the victory for the Kuruc by attacking Heister in the rear at the right time. The reasons given for his absence included the personal differences between Károlyi and Forgách, their different views on the way of fighting, the instructions he had received from Bercsényi (to try to preserve his army), or the fact that he did not consider it important to intervene quickly, given the fivefold superiority of the Kuruc army.

Forgách fled towards Pápa, then, around 14-15, met Károlyi in Sárvár, who, although he heard the battle, as we said, could not intervene in the fight or didn’t want to. His vanguards arrived at the Koroncó field after the battle. The crossing of the Rába, the journey that had been made, and the fighting had exhausted Károlyi Sándor’s army.

Heister managed to crush the Transdanubian Kuruc army in a single battle, but he was unable to regain control of the Transdanubian part of the country. He had to retreat towards Magyaróvár. The battle is described in contemporary accounts as particularly bloody. This was due to sustained cannon fire and a long period of pursuit. Different reports give different figures for the number of casualties. The casualties were heavier on the infantry than on the hussars. The losses of the Hungarian side can be estimated at around 2,000, those of the Imperial side at only 100.

The rebel officers cannot be accused of cowardice, nor was Forgách a traitor, as was later rumored. The defeat was caused by the lack of training, indiscipline, disobedience to orders, lack of trained noncommissioned and commissioned officers, and lack of adequate infantry and artillery, so characteristic of the Kuruc army.

Forgách retreated with his remaining army to Pápa and then to Sárvár. He informed Rákóczi that if he wanted military victories, he would either have to accept foreign mercenaries or organise regular Hungarian troops. “If there is no regular army besides this, we will not proceed with it”. After the defeat at Koroncó, Transdanubia was not completely lost to Rákóczi, for Heister retreated to Mosonmagyaróvár, and some of the scattered Kuruc troops soon rejoined Forgách’s or Károlyi’s army. Rabata, invading Transdanubia from Styria, was defeated by Károlyi at Szentgotthárd on 4 July 1704.

Rákóczi tried to find a solution to this problem throughout the War of Independence, but failed. The Kuruc lost the open-field battles, but the smaller raids, harassments, ambushes, and superior numbers could compensate for the losses in the fighting for years.

Sources: Szibler Gábor and Szócsinné Vitéz Léber Ottilia

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn