The following article is written by Babucs Zoltán, a military historian and researcher of the Hungarian Research Institute:

On August 30, 1940, Divine Providence manifested itself once again: the Second Vienna Award was born.

However, to force this dual-power decision, the determination of the Kingdom of Hungary was necessary, which did not please the Germans at all, since 1938, our country had opposed the Führer’s will for the third time. The first occasion was on August 22, 1938, when the Regent (Horthy Miklós) rejected the idea of Hungary attacking Czechoslovakia. The second time was on September 10, 1939, when, citing the thousand-year-old Polish–Hungarian friendship, he refused to allow the Wehrmacht to use the railway lines of Upper Hungary.

After the signing of the Second Vienna Award in the Belvedere Palace, Tamási Áron remarked that “even truth can be gotten used to.” On September 5, 1940, amid the ringing of church bells, the troops of the Royal Hungarian Army crossed the Trianon border and set out to once again take possession of part of our thousand-year-old heritage: Northern Transylvania and Székely Land. As the regimental bands played the Erdélyi induló (“Transylvanian March”) without ceasing, the army marched forward.

This was one of those moments of the stormy twentieth-century Hungarian history that every Hungarian experienced with cathartic emotions. These lands returned to the Holy Crown of Hungary, and for those living in the mother country, it was a true festival of joy, since part of the injustice of Trianon was corrected. For the Hungarians in other detached territories, it reinforced their faith that the Hungarian homeland would not forget them.

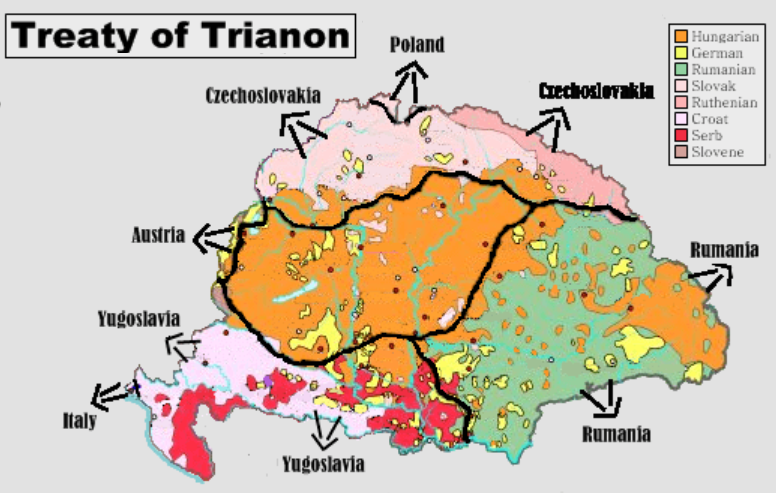

After the Treaty of Trianon of June 4, 1920, only a few dared to believe that “there will yet be a Hungarian resurrection,” and that with little bloodshed and with international approval, several of the detached territories would return into the bosom of the mother country. All this happened with the participation of an army whose right to rearmament was only recognized on August 29, 1938, in the Bled Agreement by the Little Entente. The army’s qualitative and quantitative development had only just begun, with the launch of the Győr Program in the spring of 1938. The modernization of the Royal Hungarian Army was in full swing – having to make up for two decades of delay – when the era of territorial gains arrived.

According to the First Vienna Award, on November 2, 1938, we regained southern Upper Hungary and southwestern Carpathian Ruthenia. With the disintegration of Czechoslovakia, the Carpathian territory of historic Hungary also became reattachable. On the 15th of March 1939, the troops of the Royal Hungarian Army – with German approval – launched an independent operation to take possession of these areas. By 1940, however, the attention of the truncated motherland turned toward Transylvania, as the Wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg successes in Western Europe triggered political and military reactions in all countries neighboring Hungary. Partial mobilizations also took place in Romania, which in turn prompted the Hungarian political and military leadership to take similar steps.

On May 13, the Hungarian high command ordered mobilization for the II Corps in Székesfehérvár, the VIII Corps in Kassa, the 1st Mountain Brigade in Carpatho-Ruthenia, and partially the Motorized Corps in Budapest as well. As a result of the continuous mobilizations and the reinforcement of the units directed toward Transylvania, the strength of the Romanian Royal Army after May 20 had already reached one and a half million men. In response to a new wave of Romanian mobilization, on May 27, the Hungarian government decided to raise the strength of the III Corps in Szombathely and the IV Corps in Pécs to wartime levels.

When, due to Romania’s pronounced alignment toward Germany, the possibility of regaining Transylvania by armed force was once again postponed indefinitely, a new event occurred in the region. On June 26, the Soviet Union presented a note demanding that Romania “return” Bessarabia and Bukovina. At this time, the Hungarian government – completely distancing itself from the Soviets – decided to advance territorial claims of its own against Romania. When the Romanians yielded to Soviet pressure, with the approval of the Supreme National Defence Council, the government ordered the mobilization of the army. From June 29, it was first decided to move forward the border guard battalions to the Romanian frontier, while the corps that had already been mobilized earlier or in these days (the III, IV, V Corps in Szeged, VI Corps in Debrecen, and partly the Motorized Corps) were to prepare for railway transport by July 2.

When, at dawn on June 28, the Soviet Red Army entered Romanian territory, the Romanian government ordered general mobilization due to the greater-than-expected Soviet occupation, the uncertain domestic situation, and the need to defend other borders. The Hungarian government also reacted. As it did not receive a satisfactory explanation from the Romanian side regarding the true reason for the mobilization, it mobilized the still peacetime-strength I Corps in Budapest and VII Corps in Miskolc as well, thus extending mobilization to the entire Hungarian armed forces.

The deployment and positioning of the 550,000-strong mobilized Royal Hungarian Army was completed by July 13. The three army headquarters were deployed to the future operational area on July 1, and the subordination and positions of the army corps were determined by the planned operation against Romania.

The headquarters of the 1st Army, led by Infantry General Nagy Vilmos of Nagybaczoni, born in Parajd, was stationed at Nyíregyháza-Sóstó (with I, II, IV, and VI Corps under its command), forming the main strength of the army. On the left wing of the 1st Army, between Huszt and Nagybocskó, was the 3rd Army under the command of Lieutenant General Gorondy-Novák Elemér (headquarters at Beregszász), consisting of VII and VIII Corps and the Motorized Corps. On the right wing of the 1st Army was the 2nd Army, under the command of Lieutenant General vitéz Jány Gusztáv, headquartered at Törökszentmiklós, with III and V Corps positioned on the border section between Nagyvárad and Arad.

Thanks to the Győr Program, the 1940 order of battle of the Hungarian army included 192 tanks (120 light and 72 medium), 45 armored cars, 4 armored trains, and 180 aircraft (104 reconnaissance, 24 fighters, 52 light and heavy bombers). The units stationed in Carpatho-Ruthenia and the Tiszántúl Region, along the eastern Trianon border, continued the prescribed training, while also preparing assault patrols capable of breaching the Carol Line.

Under pressure from the Axis powers, Romanian–Hungarian negotiations were held at Turnu Severin (Szörényvár) between August 16–24, but they ran aground. At that point, the Hungarian government decided to bring matters to a head and to commit the army to battle. Hungarian troops were to assemble for the attack on the night of August 26–27, occupy their designated starting positions, and at dawn on the 28th, on the order of Infantry General Henrik Werth, Chief of the General Staff, launch the offensive along the entire length of the border.

Although Hungarian society expected an easy entry, the government and the high command were well aware that after the evacuation of Bessarabia, the Romanians had transferred significant forces to their western border. Thus, the Hungarian army could achieve success only at the cost of great bloodshed, and even that was not guaranteed, since the army lacked heavy artillery capable of destroying the Romanian fortification system.

The Hungarian military leadership informed the Führer that, in terms of morale and combat readiness, the Hungarian army stood far above the Romanians, while in terms of military technology, the Romanians had superiority in aircraft and tanks by a ratio of 5 to 2. (By contrast, according to the 2nd Department of the General Staff, the combat value of the two armies was equal, and it rated the organization and training of the Romanian army as good.) This offensive plan had already been played out two years earlier as a war game at the Military Academy, which foresaw the breaching of the Carol Line, the stalling of the Hungarian offensive, alternating battles caused by Romanian numerical superiority, and finally predicted a stalemate rather than a Hungarian victory.

On August 25, along the Romanian–Hungarian border, the Romanian army had massed 16 infantry divisions, 2.5 cavalry divisions, 3 mountain brigades, 1 fortress brigade, and 1 motorized brigade. According to Hungarian reconnaissance, in the region of the Carol Line, the Romanian command had concentrated 400–450,000 soldiers, 270 tanks, and 380 aircraft; moreover, in terms of artillery and anti-tank guns, they also held superiority. The Romanian troops in Transylvania were subordinated to the Western Army Group, formed from the Romanian 1st Army Headquarters (Cluj/Kolozsvár) under the command of General Gheorghe Florescu. Their forces were divided into two groups (northern and southern) and an army reserve.

The main striking force of the Hungarian attack was to be the 1st Army (12 brigades), to which the bulk of the Motorized Corps (2 motorized and 1 cavalry brigade) was also assigned. Between Nagykároly and the Szamos River, it was to break through the Carol Line, which stretched 300 km in width and consisted of 320 concrete bunkers, numerous field fortifications, anti-tank ditches, and technical barriers. After this, it was to wear down the Romanian grouping in the Szilágyság and, together with the 3rd Army (6 brigades, 1 cavalry brigade), reach Cluj (Kolozsvár) and Dés. If, even with the Motorized Corps, it proved unable to break through the fortified chain at the Szamos Valley gorge near Szinérváralja, then the mobile forces were to be employed in pursuit through the breach created by the 1st Army.

The 3rd Army, reinforced with the 1st Cavalry Brigade from Nyíregyháza, was to support the 1st Army’s operations on its left wing. Its main attack was to begin from Máramarossziget toward Dés, with elements advancing toward Nagybánya, and after occupying the Visó Valley, reach the ridge of the Carpathians. If the advance of the 1st Army stalled in the Szamos Valley, the 3rd Army was to assist in breaking through. Meanwhile, on the right wing of the 1st Army, the 2nd Army (6 brigades) was to defend behind technical barriers, to absorb possible Romanian attacks. The left wing of this army was to follow the 1st Army’s advance and, bypassing the Carol Line from the south, reach Nagyvárad. In the extremely tense situation, on August 27, the Hungarian Air Force received orders to shoot down a Slovak aircraft violating the border.

In the end, however, a Hungarian–Romanian war did not break out, because the Romanian envoy in Berlin, on behalf of his government, requested German–Italian arbitration. Thus, the delegations of the two countries again gathered for consultations in the Belvedere Palace in Vienna. The Axis powers did not wish for the collapse of the Romanian state, and therefore, the Second Vienna Award, announced on August 30, served the interests of Germany and of a Romania that could retain its industrial districts, rather than those of Hungary.

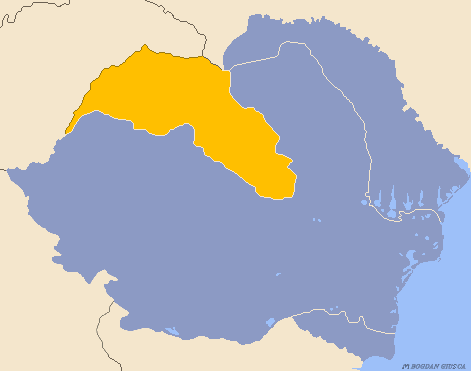

To the Kingdom of Hungary were returned the Partium, Northern Transylvania, and Székely Land: 43,492 square kilometers, with 1,344,000 Hungarians, 1,069,000 Romanians, and 47,000 Germans. The new border began at Nagyszalonta, passed south of Nagyvárad, Bánffyhunyad, and Kolozsvár / Cluj, continued around Torda, then south of Marosvásárhely, Székelyudvarhely, Sepsiszentgyörgy, and through Zágon and Kovászna reached the thousand-year-old frontier at the Carpathians.

The occupation of the “more beautiful but poorer” half of Transylvania began on Thursday, September 5, at 7 a.m., when the troops of the Royal Hungarian Army crossed the Trianon border to the sound of church bells, after the Regent’s order of the day was read to them:

“Soldiers! Another part of the injustice of Trianon has been redressed. We set out to reclaim yet another part of our thousand-year-old heritage. We bring liberation to our Hungarian brothers in Transylvania who have lived in chains for 22 years, and love to the loyal nationalities living within our borders. Keep this in mind as you march forth in the name of God and the Homeland: Forward, to the crest of the Eastern Carpathians!”

The army had only two weeks to take possession of the territories of Northern Transylvania. Therefore, its armed and live-ammunition-equipped units, which had been concentrated for the attack of August 28 and arranged along designated marching routes, participated in the reattachment operation. The units of the 1st Army stationed between Nyíracsád and Kisvárda, after crossing the Nagyvárad–Szatmárnémeti line, marched in the direction of Dés–Marosvásárhely. The corps of the 2nd Army – except for the V Corps, which was tasked with securing the Hungarian–Romanian border between Szeged and the Fekete-Körös River – advanced after leaving Nagyvárad along the Kolozsvár–Érmihályfalva–Szilágysomlyó–Dés route toward Szamosújvár. The 3rd Army crossed the border at Técső, then, passing through Beszterce and Szászrégen, marched into Székely Land.

The mixed Hungarian–Romanian military commission, which met several times in Nagyvárad, also determined the procedures for the handover and takeover of territory: Hungarian forces could begin entering the areas to be taken over at 7 a.m. each day, and the Romanian rearguards had to vacate them two hours before the arrival of the Hungarian troops. After the Hungarian high command worked out the details of the entry, these orders were received by the three army headquarters on September 2. The marching troops had to carry out their daily routes in such a way that they had hardly any opportunity for rest until they reached their designated destination for the day.

The Chief of the General Staff gave the following instructions concerning the behavior of the entering troops:

“The appearance and conduct of the entering troops must be impressive, commanding respect, and pleasing. The troops must march in order through the larger settlements. […] Discipline must be maintained even if they are swept away by patriotic enthusiasm and celebration. […] The members of the liberating troops are not called upon to exercise retribution against those responsible for the past 22 years. The troops must be instructed to refrain from individual actions. If retribution is necessary, it will be carried out by the organs of the military administration. […] Upon entry, all officers, officer cadets, and those in similar positions must wear the uniform and equipment prescribed without exception. […] During the occupation, Romanian soldiers left behind to guard important facilities, structures, demolition preparations not yet dismantled, etc., must be protected from possible outbreaks of vengeance, insults, or abuse accumulated among the population over 22 years. […] The Hungarian and German populations must be treated with the greatest affection and courtesy. The treatment of Romanians and other nationalities must always be measured, correct, and characterized by humanity worthy of the Hungarian soldier. […] Where the population suffers from food shortages, the army must extend its helping hand (distribution of leftover meals, etc.). In those settlements where the population prepares a ceremonial reception, it must be appropriately received and reciprocated on the part of the military.”

The troops had to occupy the following stages day by day:

- September 5: Érmihályfalva, Nagykároly, Szatmárnémeti, Máramarossziget

- September 6: Nagyszalonta, Nagyvárad, Margitta, Tasnád, northern Nagybánya, Aknasugatag

- September 7: Mezőtelegd, Élesd, Szilágysomlyó, Magyarlápos, Naszód, Nagybánya

- September 8: Királyhágó, Zsibó, Dés, Sajómagyarós, Beszterce

- September 9: Bánffyhunyad, Hidalmás, Szamosújvár, Szászrégen, and the Maros Gorge

- September 10: Bonchida, Marosvásárhely, Parajd, Korond, Gyergyószentmiklós, and the Gyergyó Basin

- September 11: Cluj (Kolozsvár), Székelyudvarhely, Székelykeresztúr, Csíkszereda

- September 12: Barót, Nagybacon, the southern part of the Csík Basin

- September 13: Sepsiszentgyörgy, Kézdivásárhely, Zágon

The commission also decided that Hungarian troops could reach Cluj (Kolozsvár) only at noon on September 11. However, the territories returned to the Kingdom of Hungary by the Second Vienna Award had to be fully occupied by 6 p.m. on September 13. This task was impossible to accomplish with the exhausted infantry corps alone. Therefore, when the line Cluj(Kolozsvár)–Dés–Naszód was crossed, elements of the Motorized Corps (the 1st Motorized Brigade from Budapest, the 2nd Motorized Brigade from Munkács, the 1st Cavalry Brigade from Nyíregyháza, and the 2nd Cavalry Brigade from Kecskemét) were sent ahead to Székely Land.

On September 12, the units of the Motorized Corps reached the Barót–Nagybacon–Csíkszentgyörgy–Torja line. On September 13, with the occupation of Kézdivásárhely, Sepsiszentgyörgy, and Zágon, they secured Székely Land, while the infantry columns continued to arrive there until as late as September 21.

The Hungarian-speaking population of the towns and villages that returned, especially the purely Hungarian block of Székely Land, welcomed the entering troops with deeply moving joy, triumphal arches, showers of flowers, national flags, decorated buildings, and hearts and souls dressed in festive Hungarian spirit. The soldiers could feel as if they were the victorious warriors of Prince Csaba returning home. Although pre-regime-change Marxist historiography depicted these receptions as kitsch or as mere deception by the “Horthy regime,” all those who experienced it – both the Hungarian population liberated from Romanian rule and the Hungarian soldiers entering – lived it as a cathartic festival of joy.

Hungary’s Regent, vitéz Horthy Miklós of Nagybánya, elevated the solemnity of the entry with his presence, appearing at celebrations in several Transylvanian cities: on September 5 in Szatmárnémeti, on September 6 in Nagyvárad, on September 15 in Kolozsvár (Cluj), then on September 15 in Marosvásárhely, and on September 16 in Szászrégen.

One of the most impactful – yet soldierly brief – speeches of his career was heard by the masses of returned Hungarians in Kolozsvár (Cluj):

“I greet with joy from Kolozsvár the regions of Transylvania returned to the country.

After twenty-two years of bitter trials, what I never ceased to hope for, not even for a moment, has come true. And now, when I can finally stand here on the free soil of free Transylvania, I am so deeply moved by the grandeur of this historic moment that I can hardly find words worthy of expressing my emotions.

The joy of the present mingles in my soul with the sorrow of the past, and the question rises in me: how could this suffering have befallen us Hungarians? With a clear conscience, I answer before the tribunal of history: it was not our fault! Fate placed us here on the borderland between East and West; for centuries, our homeland was the battlefield on the highway of destructive world history. While the other happy nations of Europe could grow and strengthen in peaceful labor, the Hungarians bled, perished, and dwindled in ceaseless struggles.

Meanwhile, foreign nationalities infiltrated – sometimes because they had to flee before enemies, sometimes because they hoped for prosperity here. Our ancestors not only accepted them but also granted them every freedom and guaranteed these rights by law. No one could justly complain of oppression in this homeland – and yet this served as the false pretext for mutilating, dismembering, and humiliating our thousand-year-old country. It was not weapons that deprived us of our territories, but the so-called peace treaty.

But we want to cast a veil over these sad memories. The suffering of this liberated land has come to an end, and perhaps some good will remain from it. For we know that too much prosperity, idleness, and carefree existence soften and corrupt both body and soul. Oppression, suffering, and struggle, however, temper man, increase his resilience, and keep alive his love of country. I believe that our liberated brethren, who in these happy days have strewn flowers in front of our entering soldiers with jubilant hearts, will return to the embrace of the homeland with bodies and souls strengthened and steeled – as loyal sons of the nation even in the harshest times.

That this return could take place without bloodshed in the middle of a Europe engulfed in flames – for this, here and now, I once again express heartfelt thanks to our two mighty friends: Germany and Italy.

A sad chapter of Hungarian history is coming to a close. Let the weekdays of labor follow the celebration. Everyone must take part in the work, including those of non-Hungarian mother tongue, for whoever gives no cause for complaint will prosper among us as well. Toward them, the spirit of reconciliation and fair treatment will prevail, for we expect the same fate for our brethren who have remained beyond the borders. What we promise, we shall keep, for the noble outlook of our race does not allow us ever to deviate from the straight path of truth.

In thought, every Hungarian is here today.

With sincere, deeply felt love, we think of those brethren who have not yet returned to the ancient homeland. I ask them to persevere and continue their peaceful work. We watch over their fate. We hear that they are subjected to harsh trials these days, but we believe their Calvary will soon end. We believe this, for without it, the improvement of Hungarian–Romanian relations would be impossible, but we also believe it is in the interest of the Romanians living in Hungary.

I know the serious, resistant, and combative qualities of Transylvanian youth; therefore, I look with full confidence upon the young people who have grown up here, whom we now call upon, at this turning point of fate, to devote themselves to the great national goals, for the good of the homeland and all of Europe. May God’s blessing accompany our nation toward a happy and glorious future.”

The Second Vienna Award was ratified by the Hungarian legislature with Act XXVI of 1940 (On the Reattachment to the Holy Crown of Hungary and the Union with the Country of the Eastern and Transylvanian Territories Liberated from Romanian Rule). The preamble of the Act contained the following lines:

“Strengthened in its faith in the triumph of justice, the Hungarian nation and the Hungarian legislature give profound thanks to God with deepest devotion, for now part of the Eastern Hungarian and Transylvanian territories that had been torn away has also returned to the body of the Holy Crown of Hungary. After twenty-two years of suffering, the Hungarian homeland, with the care of a loving mother, embraces her long-yearned-for, spiritually strong brethren and all her faithful sons.”

Despite the peaceful nature of the army’s entry, it nevertheless demanded blood sacrifice. As a result of accidents with weapons, military equipment, or explosives, 24 men were fatally wounded, while 89 died due to accidents or illness – among them Captain Maderspach Viktor, a reserve hussar officer, one of the “daredevils” of the 1916 fighting in Southern Transylvania, who succumbed to injuries from a traffic accident.

In connection with the entry into Transylvania, mainstream Hungarian historiography – together with the Romanians – has drawn from the incidents at Ip and Treznea the conclusion that the military operation was characterized by a series of excesses by the Hungarian army. On this matter, it must be noted that before the entry, the Romanians themselves committed several border incidents, and because of the tense, powder-keg atmosphere, the Romanian–Hungarian joint military commission had agreed that civilians offering armed resistance to the entering Hungarian troops would be treated according to international agreements, and the Hungarian military authorities would regard them as francs-tireurs. The Romanian side undertook that the evacuating authorities would collect weapons from the civilian population, and that threatening behavior, attacks against persons and property, as well as arson and destruction, were to be prevented.

However, the surrender of weapons was carried out in a Balkan manner – partially, or not at all – and this had serious consequences, when – often hotheaded – Romanian snipers fired at the Hungarian troops. These unlawful attacks were retaliated against by the Hungarian military police in the interest of order and public safety. This is what happened in the Szilágyság region, known as the cradle of the Maniu Guard, where the 32nd Infantry Regiment from Budapest received explicit orders:

“[…] All armed or otherwise dangerous attacks and attempts by Romanian forces or individual soldiers against our units must be immediately, firmly, and mercilessly retaliated against, as a deterrent example.”

Hundreds of thousands of soldiers of the Royal Hungarian Army took part in the reattachment of Northern Transylvania and Székely Land, fully armed and equipped. It was a divine miracle that the use of weapons occurred only on a few occasions. Although the Hungarian authorities tried to deal with the Romanian population with caution, while at the same time in Southern Transylvania the Hungarian population was continuously harassed by the Romanians, in 1944, the Romanian retaliation, presented as the “1940 Hungarian repressions,” nevertheless came.

After we ended the Second World War once again on the side of the losers, the Paris Peace Treaty of February 10, 1947, deprived us of all the territories that had been returned between 1938–1941. The memory of that mirage-like period of territorial gains was condemned to oblivion not only in Hungary but also in our national parts forced under foreign rule by the communist regime.

Since the political changes of 1989–1990, we have been free to speak of this period, yet even today, there are “historians” wrapped in “national colors” who brand those few years as pointless and unnecessary, dispute their results, and highlight mainly their negative aspects.

Yet the short, less than four-year-long “Little Hungarian World” gave immense spiritual strength and intellectual ammunition to the Székelys and Hungarians of Transylvania. It helped them survive even the darkest decades of communism, and even today, it gives them strength and faith. Thanks be to the Almighty that from this spiritual “provision for the road” of national reunification, the Hungarians of the once-returned Upper Hungary, Carpatho-Ruthenia, and Southern Hungary also received their share in abundance!

Source: (with footnotes) https://mki.gov.hu/hu/hirek-hu/evfordulok-hu/az-erdelyi-csokhadjarat

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn