I would like to share with you the guest article by Vlasics Bálint, which provides a broader international context for the Revolution. Read his article:

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was one of the most radical movements in East-Central Europe against the Soviet Union. The Soviet leadership used drastic measures to put an end to the unfolding political crisis. The Hungarian Revolution was a real media event of the period, which, thanks to the modern press, the Western world was able to follow in detail, while remaining passive spectators of events in Hungary. It is a less well-known fact that the only country in Europe to offer to help the Hungarians was a far-right dictatorial regime – General Franco’s Spain. However, this may raise several questions, first and foremost, what links could a geographically remote, fascist regime that denounced democracy have with an anti-Soviet movement? The Spanish state under Franco was ready to provide real military aid to the Hungarian rebels. Would Spanish intervention really have been possible?

Spain and World War II

To understand the situation and politics of Spain after World War II, it is essential to understand the Spanish Civil War and its involvement in World War II. The country’s brutal civil war can be seen as a prelude to World War II, which became a prelude to the period of Francoism that followed. The two opposing sides in the war were the republicans and the nationalists, and their struggle determined the three years of warfare that ultimately divided Spanish society into two, amidst huge losses.

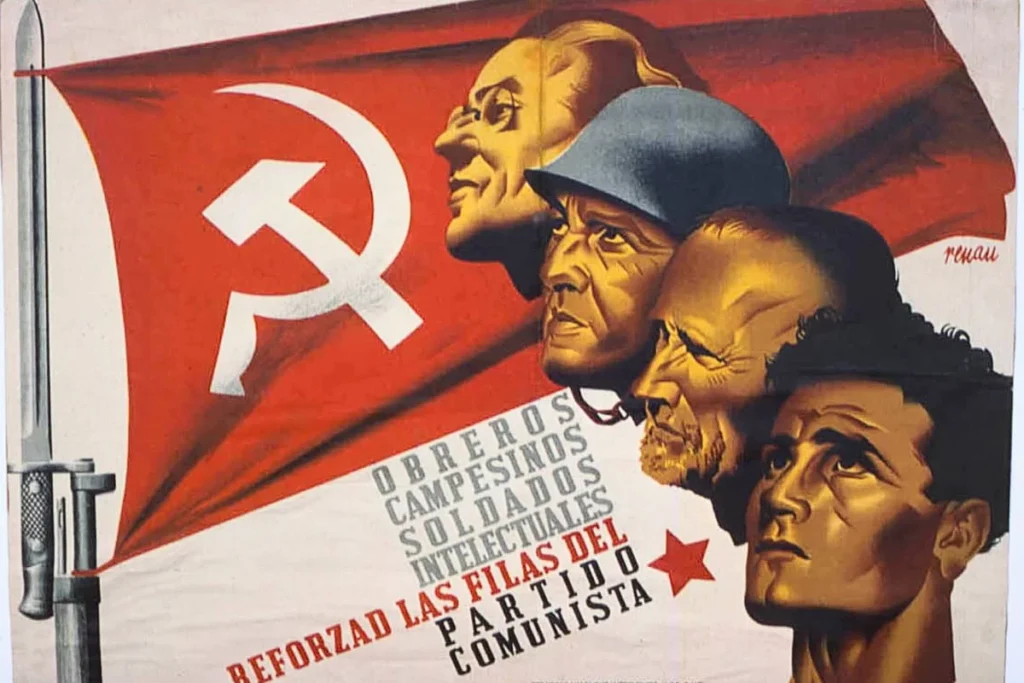

International support was of particular importance and determined the outcome of the Spanish Civil War, as both sides were backed by different powers. Franco’s side, which represented the nationalist camp, received significant support from the ideologically aligned far-right powers Germany and Italy. On the other hand, the British and French, who wanted to block the far right, could have supported the republicans, but they took a neutral position, so the Soviet Union came out in support of the republicans.

After the civil war, two types of Spain emerged on the continent. One was the Spanish government in exile, organized from republican circles and led by José Giral, which was formed in France and formally recognized by the great powers after the war, thus excluding Franco and his regime from European diplomacy. The other Spain, in fact, was Franco’s regime, which became one of the longest-running right-wing dictatorships of the 20th century on the continent. The institutionalized dictatorship was characterized by the fact that the leader (caudillo) was the sole holder of power and embodied legislative and executive power in one person. The state and party organizations and the industrial unions were organically intertwined, so that there was a single party in Francoist Spain, the FET y de las JONS (Tradicionalist Spanish Falange and Attacking National-Syndicalist Juntas), which had various auxiliary organizations. Censorship became commonplace, the use of the languages of national minorities was banned, the Cortes made the laws instead of parliament, and a three-member Governing Council was set up to prepare for Franco’s succession in accordance with the will of the Caudillo.

Franco knew full well that his country would not tolerate another war, so he did his utmost to remove himself from World War II, knowing that by engaging in war, he was risking the fate of his system. In the face of the emerging shortage of goods and the emergence of the black market, it limited its external power, which it achieved by introducing an autarkic (independent) economic policy. Although they supplied the Germans with munitions, the Anglo-Saxon powers supplied Spain with oil and grain in exchange for neutrality, as Britain and the USA recognized Spain’s geopolitical importance in the Strait of Gibraltar.

Despite this, the victorious powers at the United Nations (UN) Conference of 1945 and the Potsdam meeting declared that the country could not be admitted to the organization as long as the fascist-assisted regime was in place. This led to a diplomatic isolation of Franco’s Spain, while the great powers, in turn, recognized the Spanish government in exile as being opposed to Franco. At the suggestion of the UN, several states withdrew their ambassadors from Madrid, which led to a weakening of Franco’s regime and authority abroad and at home in the first years after the war.

The turning point came during the presidency of Harry S. Truman (1945-1953), when the US became more comfortable with the dictator’s extreme anti-communist stance during the initial Cold War. However, the process of rapprochement between Spain and the United States was extremely slow, characterized in the early years by a high level of mistrust, exacerbated by the various UN sanctions, the fact that the country was not extended Marshall Plan aid, and that it remained outside NATO. In 1950, the UN lifted the diplomatic blockade on Spain as a result of the easing of the situation. This was partly because the Spanish government-in-exile, supported by the major powers, had become too pro-Soviet and was rendered indecisive by internal differences.

The geopolitical role of Spain was particularly enhanced during the Korean War (1950-1953), which led to the start of negotiations with the country during the presidency of Dwight Eisenhower (1953-1961), in preparation for military cooperation. On 26 September 1953, the Spanish-American military cooperation agreement was signed, allowing the US to establish four military bases (three air and one naval) in the country. Also in that year, a concordat was signed with the Papacy, confirming the Catholic religion as the state religion. All this increased Franco’s international prestige and contributed greatly to the recognition and legitimacy of his regime. This was illustrated by Spain’s admission to the United Nations on 14 December 1955.

Spanish-Hungarian relations in the first half of the 20th century

The first Spanish-Hungarian relations were established in 1848 through the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, a relationship that lasted until the end of World War I and served to pave the way for diplomatic relations between the new nation-states. Hungary became of particular importance to the Spanish, as it occupied a place of mediation towards the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and Asia Minor. In 1922, relations with Madrid were regularised so that the ambassador in Paris held the Spanish post. There was no permanent Hungarian ambassador in Madrid, and until 1939, Hungary was represented only by proxies. Spain had a unified ambassadorial presence in Hungary until 1937, when the two separate governments had separate representatives in Budapest. In the meantime, the Hungarian government severed its relations with the Spanish Republic in February 1938, thus officially recognizing the Franco government, and relations between the two sides remained quite cordial until the end of World War II – this was mainly due to the perceived similarities between the Horthy and Franco regimes.

During the Spanish Civil War, it is also worth mentioning the participation of Hungarians in the formation of the international brigades organized to help the republicans, numbering nearly 1200 people, half of whom were communists. By 1937, the Republican army had set up four international brigades, the fifth of which, led by the Hungarian General Gálicz, arrived in the country in February. Research has uncovered and identified 965 Hungarian names on the Republican side – e.g., Münnich Ferenc, Kepes Imre, Rajk László. Here we can also mention Gerő Ernő, who is credited with masterminding the bloody massacres as the Soviet secret service agent in Catalonia – not coincidentally, his actions earned him the nickname ‘Barcelona executioner’.

As a result of World War II, diplomatic relations between the two countries were severed on 25 April 1945 and were not effectively restored until 1977. This was largely due to the anti-communist nature of Franco’s regime – it is no coincidence that those fleeing communism chose Spain as a temporary or permanent destination. Franco founded the Colegio Mayor Santiago Apostol (College of St Jacob) in 1946, with the aim of welcoming nationalities who had fled their homeland to escape communism. The college had a total of 16 nationalities – including Poles, Ukrainians, Croats, and Hungarians. The post-war Hungarian government, with the permission of the SZEB, established diplomatic relations with the Spanish government in exile (22 August 1946), including other countries occupied by the Soviets. However, these relations did not prove to be long-lived, as the government-in-exile was unable to satisfy both Western and Soviet interests, and because of their internal contradictions, the socialist countries severed relations with them in 1949, one after the other – only Yugoslavia, a “special path” country, did not do so, maintaining relations with the government-in-exile until its dissolution in 1977.

The role of Otto Habsburg and Marosy Ferenc

Two prominent figures played an important role in representing the interests of Hungarian refugees and supporting the Hungarian Revolution in post-World War II Spain. One of them is fairly well known for his actions, loyalty, and humanity towards Hungarians, while the other is largely unknown, as his figure and role in the revolution have been forgotten along with his actions.

Ottó Habsburg settled in Madrid in the mid-1940s, and during his years there, he led a very active social life, becoming one of Franco’s most trusted confidants and friends. According to Spanish historian Matilde Eiroa, this friendship was a major factor in Franco’s policies. It was in 1949 that, following his arrival in Madrid, Franco, at the demand of Hungarian refugees, proposed that the Hungarian embassy under Marosy should reopen the Royal Embassy at 49 Paseo de la Castellana, which had been closed since 1945, to facilitate the entry of Hungarian emigrants into the country. He also organized a 20-minute Hungarian broadcast on Spanish Radio, which began with a welcome speech by Otto Habsburg.

In 1952, the XXV International Eucharistic Congress was held in Barcelona, where Otto was asked to head the Central European Information and Documentation Center (CEDI), which was founded in 1953. Their primary aim was to act as an intermediary between Spain and Christian Democratic organizations, while at the same time increasing Spain’s international role and presence by seeking supporters, and also assisting and supporting the emigrants from Eastern Europe.

Moreover, Otto Habsburg also played a significant role in the events of 1956. At his suggestion, Franco was the first to raise his voice in support of the Hungarian events. He was in constant contact with Marosy during those fateful days and entrusted him with the task of passing on his orders to the Spanish government, asking for Franco’s help in getting the newly admitted country to propose armed intervention in the Hungarian Revolution at the UN Security Council. He also played a major role in the extraordinary solidarity shown by the Spanish people towards the Hungarian uprising, as in the late October days, Spaniards spontaneously became enthusiastic at the news of the Hungarian Revolution, and church services were held in churches throughout the country for Hungary. The Hungarian radio broadcast in Madrid was extended to twelve times its original duration, nearly four hours. Various relief and fund-raising activities were also organized, thanks to the Spanish Red Cross.

Marosy Ferenc was the head of the unofficial Hungarian Royal Embassy between 1949 and 1969. By then, he was already a well-known diplomat who had been active in foreign affairs since 1921. He had previously served on several diplomatic missions abroad, in London, Belgrade, Madrid, Bucharest, Zagreb, and, from 1944, in Helsinki. He was forced to leave Finland as a result of the Soviet-Finnish negotiations, but he did not recognize socialist Hungary and did not wish to return there, so they arrived in Madrid in April 1946, together, thanks to his good relationship with the Spanish ambassador Pedro Prat de Nantouillet, who had also left the country.

Here, he taught international law at the Complutense University of Madrid, while the Hungarian National Committee, formed by Hungarian émigrés loyal to Horthy in New York, appointed him as its representative in Spain – Marosy thus represented Royal Hungary to the Spanish government. Through the MNB’s network of envoys, they acted as ambassadors in a country and regularly reported on Hungarian interests and the activities of Hungarians in that country to the Director General of Foreign Affairs, Bakách-Bessenyei György.

In 1949, with the support of Otto Habsburg, the embassy was given back its old building and its valuables, and as a result, Marosy’s title changed: he officially became “the representative of Hungarian interests in Spain”, now as the de facto semi-official representative of the Kingdom of Hungary. He was responsible for the Hungarian radio broadcasts, which were also authorized by Otto Habsburg, and also supervised the work of the St. Jacob’s College, which enabled many Hungarian emigrants to continue their studies and obtain a degree. Marosy’s main role was also to receive Hungarian refugees and secure their visas – issuing passports and identity documents. He was mainly concerned with issuing passports valid for the USA, Canada, and Portugal, and for countries that did not maintain diplomatic missions with the Hungarian People’s Republic.

He had a particularly good relationship with Otto Habsburg. He was also a leader and organizer of the Hungarian community in Spain. Every year, the Hungarian community celebrated March 15 together at the embassy in Madrid, and after the fall of the revolution, on October 23. Marosy never returned home to socialist Hungary. He died in Spain in 1986, and his grave is still in Madrid, with the inscription SZKV, presumably meaning “outcast”. The embassy building was later demolished, but nothing is known of the building’s furnishings or documents.

The question of Spanish intervention

For Spain, 1956 was by no means an uneventful year. At the beginning of the year, Franco’s foreign policy openings led to a university riot in Madrid, which sparked a government crisis that removed several ministers and the Rector of the University from their posts. This was the first manifestation of opposition to Franco’s dictatorship, which had an impact on the regime itself. And in April, Spain was finally forced to recognize the independence of the Moroccan protectorate, and the Moroccan territory was unified.

On 24 October, news of the revolution reached Spain, and Marosy, who was at the embassy in Madrid, received a telephone call from Otto Habsburg that day. The two kept each other informed of developments, and Marosy readily complied with Otto’s every order. On 26 October, Marosy received orders from his Majesty to ask Franco to protest to the UN on his behalf against the threat of Soviet intervention. They tried to keep each other informed of all the important facts, as Marosy’s accounts show that they spoke to Otto several times on the telephone over the next few days, and that His Majesty repeatedly expressed his concern about the Soviet build-up of forces, for it was clear to him that Soviet intervention would not be long in coming. The crisis in Suez on 29 October led to a drastic international change – as a result, the UN Council suspended discussions on the Hungarian question, and it was only on 1 November that the issue was again put before the General Assembly.

“The Spanish willingness to make sacrifices is still great, but I fear that it will now be diminished when they hear that the Russians have again occupied the country without resistance. The Egyptian affair – although I fully understand the Anglo-French – has been very bad for us because it is a distraction. And it may even be seen as a bargaining chip. That’s what you should be trying to avoid now.” (Anderle Ádám: 1956 and the question of Spanish military intervention. In Hungary and the Hispanic World. Research Publications II. Ed. by Anderle Ádám, Szeged, Hispania, 2000. 58.)

The role of Spain, whose priority in the wake of the revolution was to provide humanitarian aid and to receive and support refugees, should be highlighted. On 30 October, a mass was celebrated in all the churches of the country for the liberation of Hungary. In just two days, the aid money collected amounted to $4,000 in aid for the refugees. It was also under Hungarian pressure that the Spaniards asked the UN to set up a commission of inquiry in Budapest, but there was no chance of this happening. On 3 November, at the request of Otto Habsburg, Marosy Ferenc appealed to Franco for the purchase of armor-piercing weapons worth 500,000 dollars. The purchase was to be made with MNB funds, but on 4 November, the day of the Soviet intervention, Marosy had already asked Franco for aircraft to deliver the weapons to Hungary.

“On Friday, 2 November, [Habsburg] Otto announced that there were rumours of a large Soviet military force gathering in Galicia, apparently with the intention of invading Hungary. On 4 November, His Majesty calls me again and informs me that the Russian army has crossed the frontier and orders me to go immediately to Prado and ask Franco in his name to send help to the Hungarian freedom fighters.” (Soviet military intervention. Ed. by Györkei Jenő – Horváth Miklós, Argumentum Publishers, Budapest, 2001.)

There is every indication that Franco was quite determined to provide military assistance, for on the day Marosy mentions, the night of 4 to 5 November, he immediately summoned the Council of Ministers, having just arrived from a hunting trip in the countryside. After a brief discussion, it was decided to send a volunteer army to Hungary. The importance of the situation and the firmness of the decision were also demonstrated by the resignation of Agustín Muñoz Grandes, Spanish Minister of Defense and former commander of the Blue Division on the Eastern Front, to take up the command of the military relief force. Franco, however, did not accept Grandes’ resignation and put Czilhert Aurel in charge of the mission. Czilhert’s task was to deliver the anti-tank weapons to Hungary in three planes. The problem was, however, that the Spanish planes could not yet have made such a long journey from Spain directly to Hungary, so they would have had to land somewhere in Germany or Austria to refuel, which raised a number of security issues. The plan was to refuel in Neubiberg near Munich and then continue on their way to deliver the weapons to the Hungarian rebels somewhere in the Szombathely area.

However, the action was banned before it started. Spanish Foreign Minister Artajo approached the US Ambassador to the UN, Cabot Lodge, and told him that Franco was prepared to support the Hungarian cause with armed forces – the only proposal to support the revolution that had come to the attention of the US leadership. The US was reluctant to support the Spanish action, which resulted in Czilher’s action being blocked by an unexpected phone call from the US on 5 November, explaining to the Spanish government that no military action could be taken to help the Hungarians without their permission.

“The United States Government shares the Spanish Government’s disgust at the brutal Soviet military action against Hungary and its deep sympathy for the Hungarian people’s struggle for independence. At the same time, the Government of the United States has regretfully concluded that there is no, I repeat, no way in which it can carry out a useful military intervention in support of the Hungarian patriots without the hope of success and without the grave risk of a major conflict with the Soviet Union. The United Nations is actively engaged in addressing the various problems threatening world peace, and the United States believes that it is in the best interests of all of us to carry these initiatives to a successful conclusion. Consequently, neither overt nor covert military intervention by the United States Government should, I repeat, should not be undertaken in Hungary under the present circumstances.” (Borhi László: Franco and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. 1956. História 9-10 (1998) 61.)

What could have caused such a strong reaction from the US? Well, America argued publicly for the liberation of Eastern Europe – using only peaceful means. According to Borhi László, the CIA was enthusiastic about the events in Hungary because it was the organization most committed to the liberation of the Soviet bloc. Understandably, the US leadership feared the possibility of another armed military conflict, as the CIA believed that the Soviet Union would have done anything to keep Hungary. However, it is an important fact that Hungary is not worth enough for the US to weaken its position in other areas (e.g., the Middle East). It is also worth pointing out that such an action would have involved violating the territories of Austria, Czechoslovakia, or even Yugoslavia.

However, it may be worth examining the US position in the light of the events in Hungary, as the target area of the arms shipments, Szombathely and its surroundings, fell on 5 November. By the next day, 6 November, everyone believed that the cause and the possibility of a Hungarian uprising had been lost. From another point of view, however, the USA had already decided after 29 October not to interfere in events in the Soviet sphere of influence – the Hungarian revolution was no exception. Some argue that Spanish intervention, even if it had been carried out, would not have turned events in a positive direction. But to look at it in a different light, we can say that no other Western state would have intervened in a military conflict within the Soviet Union’s sphere of influence without the US’s permission.

Consequences

Although the opportunity had passed, General Zákó András, commander of the Hungarian Warriors’ Comrades’ Association, arrived in Madrid at the end of November to inform the Spanish about the Hungarian Revolution and the real military situation in the country. In his solemn report, he expressed his opinion that the cause of the Hungarian Revolution was not lost and that, in his opinion, the uprising would be resumed in the spring. Two plans are supposedly linked to his name in connection with the Hungarian cause. The first, Lo que debe hacerse en este momento (What we must do at this moment), proposed the establishment of a joint military command for Central and Eastern Europe, and suggested that an uprising in the Czech Republic would be the way to relaunch the offensive against the Soviets. One of the major drawbacks of the plan was the same one that ultimately thwarted Spanish military support, as the plan stated that the operation was dependent on US funding and support. The other draft was entitled Ayuda española a Hungría en su lucha el comunismo (Spanish Aid to Hungary in its fight against Communism) and provided for the creation of a secret capital fund to fight the anti-Soviet war.

The cause of the Hungarian Revolution fell, and soon the plans for intervention were dropped from the agenda, but Hungary’s involvement in 1956 was still present in the press for a long time. In any case, Franco’s solidarity with the Hungarian cause had many positive rewards for Spain, which, for the first time since 1939, was able to appear on the international stage on the side of the Western democratic powers. Spain’s admission to the World Bank in 1958, which was intended to remedy a minor economic crisis in the country, was a sign of recognition by the Western powers. As a result, Spain’s economy boomed thanks to its growing working capital, which was only significantly curtailed by the oil price explosion of 1973.

This undoubtedly had an impact on Franco’s policies, and the decade of constitutional ‘cosmetics’ to win the sympathy of the Western powers began – one of the most spectacular and telling years of this was 1969, when Franco appointed the grandson of King Alfonso XIII, Prince Juan Carlos, as his official successor. As a consequence, by the 1970s, a welfare state had begun to emerge in Spain, with the advent of television, the car, and the telephone in households.

It is also important to mention the broadening of Spain’s diplomatic relations. From 1958-59 onwards, in the framework of the economic stabilization plan, negotiations were opened in a semi-official form between Spain and Hungary to renew the interrupted exchanges. The diplomatic initiative was launched by Spain in 1965, and contacts were established with almost all the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, in all of which the easing of tensions between the great powers played a significant role. As a result of the increase in trade and economic cooperation, ambassadors were appointed in 1977 and agreements were signed with the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia, as well as Romania, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, and Poland. Spain’s economic strength and its role in international politics are demonstrated by its accession to the European Union in 1986.

Conclusion

It is worth examining the text and content of Spanish textbooks on the relationship between Franco and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. Well, unfortunately, the results of this study prove that the events of 1956 are not properly understood, since they are considered just one of the events of the Cold War. The very term ‘1956’ is problematic, as textbooks are not specific and refer to the Hungarian events as an upheaval, revolt, movement, or crisis rather than a revolution. There is also a confusion of imagery and content, as the events are often confused with the events of the Prague Spring of 1968.

We can conclude that Franco’s Spain was ready to support the Hungarian revolution with arms. The reasons for this are complex, but the anti-communist stance of the Franco regime and its efforts to win the support of the Western powers are significant factors. However, both Franco and the European powers could only participate in operations authorized by the US, as this would have effectively led to an open military conflict between the two superpowers. As a consequence, Spanish military support for the Hungarian rebels could not be provided either then or later.

Source: https://ujkor.hu/content/1956-es-a-spanyol-intervencio-lehetosege (you can find the list of primary historical sources on that page)

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjb