Foreword: the Hungarians’ “raids” in Europe in the 9th and 10th centuries

Let me give you the summary of Király Péter’s “Thoughts on the ‘Kalandozások’ (raids)”

Király Péter’s narrative is a critical analysis of the term “kalandozások” (often translated as “raids” or “adventures”) used to describe the military campaigns of the Hungarians in the 10th century. He proposes a significant shift in how these campaigns are understood and labeled.

1. Rejection of the Term “Kalandozások”

- Linguistic Argument: Király argues that the root word “kaland” (adventure) is a late addition to the Hungarian language (first attested in 1668) and carries negative connotations like “wandering” or “roaming.” He deems this term unfair, derogatory, and inaccurate for describing the serious military and political undertakings of the Hungarian conquerors.

- Proposed Terminology: He strongly recommends replacing “kalandozások” with more neutral and precise terms like “hadakozás” (military campaigns/warfare), “hadi út” (military expedition), or “hadjárat” (campaign). “Hadakozás” is his preferred term as it encompasses both offensive and defensive warfare.

2. Reinterpretation of the Campaigns’ Purpose

Király challenges the simplistic view of these campaigns as mere plundering raids. Instead, he presents them as a complex strategy with an ultimate, unifying goal: the strengthening and consolidation of the newly founded Hungarian state (“ország erősítése, megszilárdítása”).

- They were not disorganized adventures but calculated “adóztató, zsákmányszerző és egyben biztonságot szolgáló, elrettentő akciók” (actions aimed at exacting tribute, securing plunder, and simultaneously ensuring security and serving as a deterrent).

- This strategy involved securing borders through both diplomatic treaties and military actions, which was a gradual process requiring decades.

3. Historical Context and Alliances

- Király places the campaigns in a broader historical context, mentioning Hungarian military activities before the Conquest of the Carpathian Basin (e.g., involvement in Byzantine-Bulgarian conflicts).

- He emphasizes the importance of alliances, arguing that the Hungarians often acted at the request of or in cooperation with other powers (e.g., Moravians, Slavs, the Italian king Berengar I, or East Frankish factions). This frames their actions as part of European power politics rather than isolated banditry.

4. Critique of the Sources

- He highlights the problem of source bias. Contemporary accounts come almost exclusively from foreign (often hostile) chronicles that used topoi like “cruel, bloodthirsty people” to describe the Hungarians.

- Later Hungarian chronicles (e.g., Anonymous’s Gesta Hungarorum) and legends (e.g., the Legenda maior of St. Stephen) focus on the peaceful integration and state-building, emphasizing a shift towards peace under leaders like Géza and Stephen I.

5. Comparison with Other Peoples

- Király draws a parallel with the Bulgarians, who also migrated to the Danube region. He contrasts their fate (linguistic assimilation/Slavicization due to a smaller population and the use of Old Church Slavonic in liturgy) with the success of the Hungarians in preserving their language and identity (aided by a larger population and the use of Latin).

6. Acknowledgment of Plunder, but within a Strategy

While not denying that plunder (“zsákmányszerzés”) was a component, Király argues it was not the sole or even primary driver. He cites examples from other eras (e.g., the sack of Carthage by Rome) to show that destruction and plunder were common practices in warfare, not unique to the Hungarians. The ultimate aim was always the long-term security of the homeland.

Core Thesis

Király Péter’s core argument is that the Hungarian campaigns of the 10th century were not “adventures” but deliberate, strategic military actions integral to the process of conquest, defense, and state-building. The term “kalandozások” is a misleading anachronism that should be discarded in favor of terminology that reflects their serious political and military nature.

Now, let us see the mainstream narrative of the Rubicon Magazine, where they used “kalandozások” (adventurous raids), but I translate it as “raids”, and will highlight the word “adventures”:

The victory of the adventuring Hungarians over Berengar

“Save us, O Lord, from the arrows of the Hungarians!”

(Prayer from the Age of the Hungarian Raids)

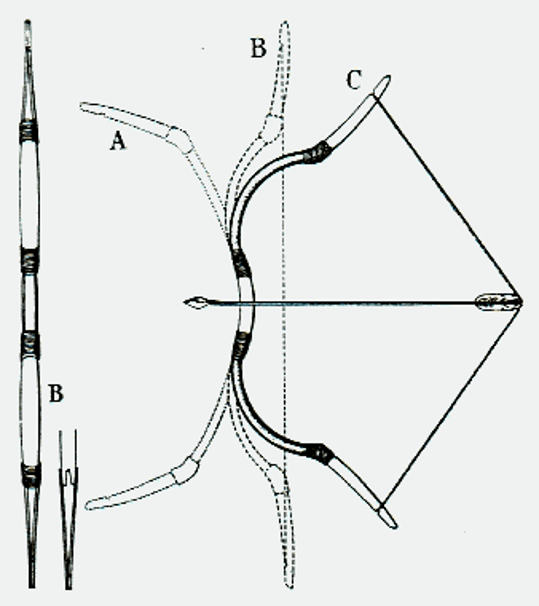

On September 24, 899, the raiding Hungarians destroyed the armies of King Berengar Friaul of Italy (r. 887-924) near the Brenta River, after their famous tactics of feigning flight had lured him into the terrain they had sought. Victory against a threefold overwhelming force was the first major success of the military campaigns of the “adventurers”, followed by the glorification of northern Italy.

In 895-96, after the Hungarians led by Árpád had conquered all of the Carpathian Basin except Pannonia, the horsemen of the confederacy soon appeared in Western Europe. The fact that the rulers of a weak and fragmented Europe saw in the Hungarians a great opportunity to realise their ambitions, and in the following decades often hired them to attack their opponents, played a major role in the “adventures”, alongside the nomads’ raiding habits and their eventual plans to migrate westwards.

The first in line was the Frankish monarch Arnulf of the East (r. 887-899), who wanted to claim the Imperial crown, but was opposed by Berengar of Friaul, King of Italy, who, by descent, was the great-grandson of Charlemagne (r. 768-814) – also claimed the title. The “adventuring” expedition of 899 was launched under the pretext of Arnulf’s commission, and in the summer of that year the Hungarian armies bypassed the previously targeted Pannonia and marched on their dashing horses along the Sava and Drava rivers – later called the Strata Hungarorum, or the Hungarian Way, because of the frequent campaigns – into northern Italy and then raided the entire Po plain. During September, our “adventuring” ancestors made their way as far as the pass of St Bernat and the seat of Berengar in Pavia, and the monarch soon organised an army of knights to drive them out.

The armies that had invaded Lombardy reacted to Berengar’s attack with – apparently – panic, and in the middle of the month they began to retreat along the ancient Via Postumia. Unfamiliar with the tactics of the Hungarians, the king of Italy was disheartened by the sight of the fleeing Hungarians, and after defeating the rearguard on the banks of the Lombardy rivers, he always thought he had defeated a serious army. The “adventuring” leaders, however, were very deliberate in their apparent flight, and in fact lured Berengar after them to meet him on the banks of the Brenta, a battlefield they had chosen at the beginning of the campaign.

While the plan was indeed ingenious, the truth is that events may not have gone entirely as the Hungarians intended, for according to reports of the battle, the “adventuring” leaders bargained with Berengar at Brenta, offering to return all the treasure they had looted and never to set foot on Italian soil again if they were free. It is not known whether the bargain was sincere or whether it was a stalling tactic, but in any case, Berengar refused the offer and, at the same time, missed the attack, making the worst possible decision.

After the negotiations were over, the Hungarian leaders suddenly gave the signal to attack, and the nomadic warriors swam across the Brenta in the blink of an eye. Berengar had surrounded his camp with a wagon fortress before the battle – a position and its consequences familiar from the tragic Battle of Muhi – and so, despite outnumbering the Hungarians three to one, the extremely fast and accurate cavalrymen decimated the trapped army in no time. The Christians, shocked by the unexpected attack, made only a feeble attempt to repulse the Hungarians, and panic soon set in at the wagon fort; everyone ran where they could see, and Berengar himself survived the unfortunate outcome of the battle only by fleeing back to Pavia dressed as a common soldier.

After the devastating blow, the “adventurers” were virtually masters of northern Italy, and they tried to exploit the victory with more raids. The Hungarian fighters spent the winter on the peninsula and attempted to take Venice, as well as Vercelli, Modena, and the monastery of Nonantola. In the spring of 900, the adventuring leaders decided to return to the Carpathian Basin, and after Arnulf died in 899, the alliance with him was declared invalid, and on the way home, they conquered Pannonia from the Franks in the East.

The “diplomacy” of the Hungarian tribal alliance is well illustrated by the fact that it made peace with Berengar in the 900s and immediately afterwards launched a war against the Franks and the Bavarians. For half a century afterwards, Western Europe was divided enough for our ancestors to use this method without consequence, but over time, nomadic tactics and fear of the ‘arrows of the Hungarians’ contributed greatly to the strengthening of Christian monarchies, notably the German-Roman Empire.

The alternative theory about the Hungarian “adventures” (raids)

The Avar Empire was the first permanent state to unite the territory of the later Kingdom of Hungary with a Carpathian Basin centre. It was able to maintain its power for almost two and a half centuries, but at the end of the eighth century, the Avar Kaganate collapsed due to the attacks of the rising Franks in Western Europe, the expansion of the Bulgars from the south, and, not least, the civil war that broke out among the Avar ranks. One of the key moments in the fall was the moment when the Avar capital was sacked almost without hindrance.

The “regaining the Avar-treasures” theory proposes a narrative that significantly reinterprets the Hungarian conquests (“kalandozások”) of the 9th-10th centuries. It moves beyond the conventional explanation of mere plunder and seeks to frame the campaigns as a mission to reclaim a lost heritage. Most of the famous Avar treasures were already looted and carried off to the Frankish Empire by Charlemagne’s forces around 796 AD, long before the Hungarian conquest. The arriving Hungarians, being the brothers of the Avars with the same language and culture, aimed to get them back.

The central idea is that the Hungarian incursions into the Carpathian Basin were not just random raids for plunder, but a deliberate effort to reclaim the land and treasures of their supposed kin and predecessors, the Avars (and to a lesser extent, the Huns). In this view, the conquest was a “re-conquest” or a “taking back of a rightful inheritance.”

- Ethnic Continuity and Kinship: The theory is built on the idea of a strong ethnic and cultural continuity in the Carpathian Basin. It suggests that after the fall of the Avar Khaganate (c. 800 AD), a significant Avar population remained. Proponents often argue for a pre-existing kinship between the Avars and the Hungarians, suggesting they were related steppe peoples. Therefore, the arriving Hungarians were not entering a foreign land but reuniting with their relatives. Some people even connect the Avars to the Huns, thus following the early medieval Hungarian chronicles.

- The “Double Conquest” Motif: This concept suggests that the Hungarian conquest of 895 was actually the second time a related steppe people took control of the basin, the first being the Avars in the 6th century. The campaigns were thus aimed at restoring the order and power of a previous steppe empire. Note, even the conservative Hungarian Academy of Science – though grudgingly – gave ground to this theory, due to the enormous work of Professor László Gyula.

- Symbolic Interpretation of “Treasures”: The “Avar treasures” are not understood merely as gold and silver. Symbolically, they represent the land itself, its strategic position, and the legacy of steppe power and sovereignty over the region. The theory posits that the Hungarian leaders were consciously reviving the Avar (and Hun) claim to dominance in Central Europe.

- Supporting Evidence (as cited by proponents): Chronicles: Later Hungarian chronicles, like the Gesta Hungarorum by Anonymous (c. 1200), which speak of a Hun-Hungarian kinship and a pre-existing right to the land, are interpreted as preserving a genuine historical tradition. Archaeology: Stylistic similarities between 10th-century Hungarian and earlier Avar artifacts (e.g., in jewelry, belt decorations) are seen as evidence of cultural continuity and a direct connection, rather than simply the assimilation of a subdued local population.

Sources: Tarján M. Tamás /Rubicon Magazine and Király Péter https://www.c3.hu/~magyarnyelv/00-2/kiraly.htm

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn