Prelude

“Reginam occidere nolite timere bonum est si omnes consentiunt ego non contradico” – wrote Archbishop János of Esztergom in his famous letter with Dodonian ambiguity.

In the autumn of 1213, a group of Hungarian lords (the “camp of the restless”) prepared and carried out an assassination attempt against Gertrude of Merania (Gertrudis), wife of King András II. The cause of the uprising was Gertrude’s action in proclaiming her brother Berthold (Otto) Archbishop of Kalocsa in the absence of her husband (who was then fighting in Halych). However, because of his youth and background, Pope Innocent III also objected to the new title and banned him from the pastoral office. Since he retained his title, he was able to gain the church’s property in the Kalocsa area without being assigned a task. However, the igniting spark of the lords’ revolt was that the queen installed her relatives in the highest posts of the state, thus giving her brother the most powerful rank of country lord.

With the help of the great landowners, Bán (Duke) Petur and the country’s Palatine, Bór Benke (better known as Bór the Bánk Bán), they conspired. They sought the advice of the then Archbishop of Esztergom, János of Merania, before carrying out the plot. The archpriest was caught between two fires. On the one hand, Otto’s appointment as prelate of the church endangered his high priestly rank, the church’s income, its morality, and its right to coronation, as well as all its other privileges. Therefore, it would have been advantageous for him to stand among the rebels. On the other hand, he would have lost not only his high rank but also his life for his involvement in murder.

Thus, in Latin, he crafted his now-famous ambiguous reply. Thanks to the work of the Benedictine monk Hermann von Altaich, the text has survived. It could be translated into Hungarian and English (the ambiguity of the text is due to the way it is written and the lack of punctuation):

In Hungarian:

“A királynét megölni nem kell félnetek jó lesz ha mindenki egyetért én nem ellenzem.”

In English:

“You need not fear to kill the queen if everyone agrees, I am not against it.”

The two conflicting meanings of the text are produced only by the use of commas:

1. Killing the queen is not necessary; it will be good for you to fear if everyone agrees, but I do not. I am against it.

(Reginam occidere bonum est timere, nolite. Et si omnes consenserint, ego non. Contradico.)

2. Killing the Queen is nothing to be afraid of; it’s good if everyone agrees, I’m not against it.

(Reginam occidere bonum est, timere nolite, Et si omnes consenserint, ego non contradico.)

When summoned to testify on charges of involvement in an attempted murder, the archpriest offered the opposing reading as an excuse, namely.

The queen need not be killed – you will fear well; if all agree – I do not – I am against it.

Confirming this, Pope Innocent III acquitted him of complicity in the assassination, nor did King Béla IV punish him.

So successful was the answer in Europe that it is cited as an example of ambiguity by Boncompagno da Signa, a famous professor at the University of Bologna who had visited Bavaria and was on good terms with the Pope, in his Rhetorica novissima of 1235, i.e., it became part of the rhetorical curriculum from that time on.

The Story, according to a mainstream Hungarian history magazine:

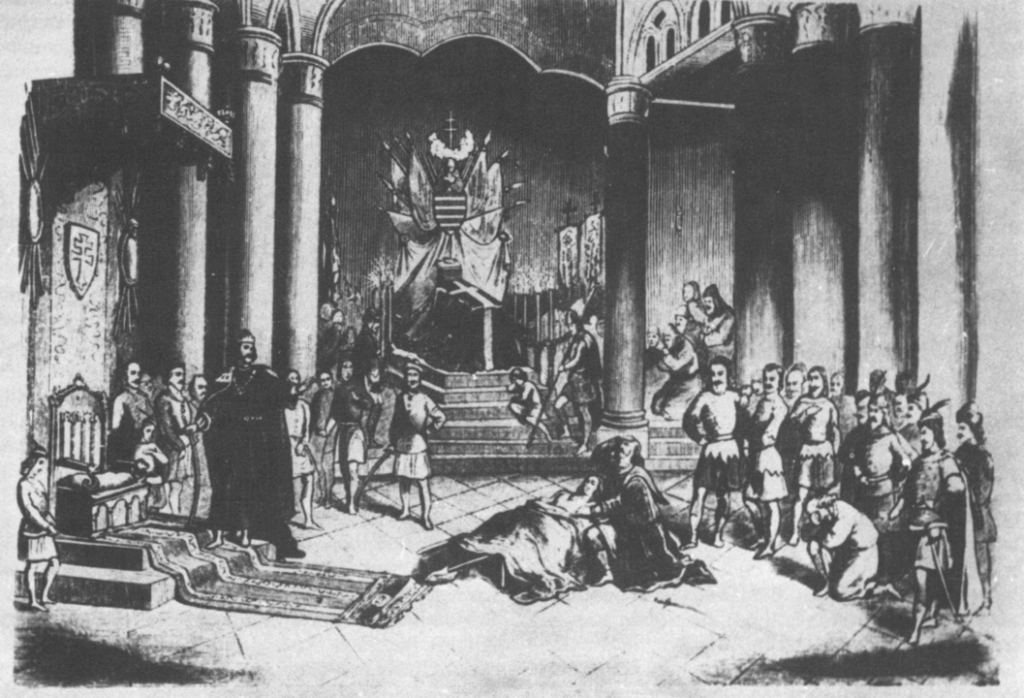

On 28 September 1213, the Hungarian queen Gertrudis of Merania, the first wife of King András II (r. 1205-1235), was assassinated by the conspirators led by Bánk Bán (Duke). The assassination in the forest of Pilis Hills, later immortalised in a drama by Katona József and an opera by Erkel Ferenc, has become one of the most famous crimes in Hungarian history, but the exact events have been obscured by the beliefs and legends that have grown up in the wake of popular works.

The Queen of Merania, one of the most unpopular queens in Hungarian history, was the descendant of an upstart princely family whose head, Count Bertold of Andechs, received Merania (not to be confused with Merano in Tyrol) from Barbarossa Frederick (r. 1152-1190).

Although the province was rather small, the ambitious Prince Bertold (r. 1183-1204) soon made a name for himself in Merania by marrying off his daughters: the eldest daughter, Agnes, was a famous beauty who, thanks to this, became the wife of King Phillip Augustus II of France (r. 1180-1223). The middle child, Hedwig, was married to a Polish prince – and later canonised – and Gertrude was betrothed to Prince András of Hungary, the younger brother of King Imre (1196-1204).

According to historical tradition, the wedding took place in 1203, the year in which András launched a major rebellion against his brother, and Gertrude was later blamed by public opinion for the conflict.

It is not known whether she actually took part in the plot, but the fact is that the prince was defeated in the 1203 internal war, after many repeated attempts. Although this time he had gathered a strong army, King Imre thwarted his plans just before the decisive battle by making an unexpected appearance in the rebel camp and discouraging his enemies with his unarmed actions and rhetoric.

András was then imprisoned, and Gertrude was sent home to Prince Bertold, only to return to Hungary after the deaths of Imre and his son László. Her unpopularity is illustrated by the fact that, despite her stay in Merania, the death of the child László III (r. 1204-1205) in Vienna in May 1205 was later attributed to her scheming.

In any case, the death of the child heir to the throne did indeed remove the last obstacle to András becoming King and Gertrude Queen. She wanted more than to administer her court and raise her five children – the future King Béla IV (r. 1235-1270), St Erzsébet, and Kálmán, Mária, and András – and soon found herself in serious conflict with the nobility of the country.

Under Gertrude’s influence, András began to lavish money on the queen’s foreign minions and members of the Meranian family, who had fled to Hungary. In the spirit of the “nova institutiones”, or ‘new establishment’, the monarch donated entire counties and key offices to ‘foreigners’, for example, Gertrudis’s brother Bertold, a provost, was first made Archbishop of Kalocsa and later was granted the Transylvanian voivodeship.

Not surprisingly, the ‘new arrangement’ soon provoked the indignation of the neglected lords of the land, who, after their complaints fell on deaf ears, hoping to put an end to the donations, decided to kill the queen.

Unfortunately, we do not know for sure about the size and the participants of the conspiracy organised in 1213, nor do we know exactly who carried out the famous assassination in the forest of Pilis Hills; later accounts, the drama of Katona József and the opera of Erkel Ferenc, of course, inevitably bring to mind the name of Bánk, the Slavonian Ban (Duke) and Palatine, but there is no concrete evidence of his involvement.

Bánk was presumably actively involved in the planning of the murder, and alongside him, Ban Simon of the clan of the Kacsics, the Comes Péter of Csanád county, and possibly even Archbishop János of Esztergom – we remember, he wrote the ambiguous sentence – were among the main organisers. The assumption that all the above-mentioned dignitaries were connected to the assassination is supported primarily by the aftermath of the case, i.e., that apart from the executed Comes Péter, the other accused were not harmed. The only possible justification for this unusual procedure was that, following the death of his wife, András felt that his throne was in danger of being usurped by the united action of the lords.

We do not have exact information about the background of the murder, but we do know that on 28 September 1213, Queen Gertrudis celebrated Pilisszentkeresz in honour of the visiting Austrian Prince Leopold VI (r. 1198-1230), which was attended by Comes Péter, Ban Simon, and presumably Ban Bánk.

This banquet provided an excellent opportunity for the assassination in several ways: firstly, because it took the hated queen away from both her castle and her bodyguard, and secondly, because her husband, King András II, was at war in Halych (now Ukraine) at the time. The noble lords presumably carried out the murder in the hills of Pilis: first, they lured the unsuspecting Gertrudis’s carriage into a trap, then they killed the queen deep in the forest and slaughtered most of her entourage.

It is said that Prince Leopold himself was lucky to survive the attack; he could flee in a commoner’s disguise. Gertrudis was probably struck down by the later executed Comes Péter, but the body of the hated woman was later slashed and mowed down by others.

As we have seen, the famous assassination did not bring about much change politically; due to the weakness of the monarch’s power, András allowed his wife’s murder to go virtually unpunished, and it was not until 1228 that Prince Béla, heir to the throne, had to wait for his mother’s death to be avenged by symbolic measures such as confiscating estates. However, the first well-documented assassination in Hungarian history later attracted the attention of chroniclers not only in Hungary but also in neighbouring countries, and around 1268 it was in Germany that the first reports were written.

Based on this work and the 14th-century Viennese chronicle, the Transylvanian Valkai András also adapted the story of the murder, but the story was then built around the figure of the alleged leader of the conspirators, Ban Bánk, and his alleged grievances.

Valkai’s interpretation explains why Katona József, and later Erkel Ferenc, based on his drama, placed Bánk at the centre of the story of the assassination of the queen, who, moreover, was no longer a Slavonian Ban, but a much more noble lord, the country’s Palatine. Despite the historical error, the demonised figure of Gertrudis and “Ban Bánk” became an integral part of Hungarian popular memory, and the conflict between the two – thanks to the talents of Katona and Erkel – perfectly expressed the antagonism between the suffering Hungarians and the oppressive foreigners.

A few thoughts

It is possible that the 26th article of the Golden Bull of 1222, which prescribed that Hungarian properties could not be given to foreigners, and the 23rd article of the Golden Bull of 1231, which prescribed that foreigners could only be appointed to court positions if they remained in Hungary (because such people only “take the country’s wealth [abroad]”), may reflect a negative response to Gertrude’s favoritism.

The Austrian Rhyming Chronicle is the earliest known work, which preserved the alleged story of how Archbishop Berthold raped Ban Bánk’s wife, which was the immediate cause of the assassination of the queen, who acted as a procuress in the adultery. According to this narration, Bánk led the conspirators and stabbed Gertrude with a sword personally. The chronicle was compiled by a Hungarian cleric in Klosterneuburg Abbey, Lower Austria, around 1270. The chronicle claims that King Béla IV ordered to slaughter of all participants of the assassination after he ascended the Hungarian throne in 1235.

The 14th-century Hungarian “Illuminated Chronicle” (Chronicon Pictum) took over the story too, which then made a decisive contribution to making the story rooted in the Hungarian chronicle and historiographical tradition and, subsequently, the Hungarian-language literature and culture.

In accordance with her will, Gertrude was buried in the Pilis Abbey, while certain parts of her body were buried in the monastery of Lelesz. King András II ordered that two priests of the monastery pray for his wife’s spiritual salvation. The ruins of her tomb were discovered during the excavations carried out by Gerevich László in the Pilis Abbey between 1967 and 1982.

Shortly after Gertrude’s assassination, King András II married Yolanda of Courtenay in February 1215. The king did not intend for the new wife to have a governmental role, as he had experienced the previous sharp opposition from the Hungarian elite. When András left Hungary to fight in the Fifth Crusade in 1217–1218, he entrusted the regency to Archbishop John and Palatine Julius Kán, instead of to Yolanda, who remained passive in political matters throughout her life. András’ third wife, Beatrice d’Este, had a similar concept of role.

The death of Gertrude and the “negative experiences” associated with her resulted in the decline of a separate queenly court in 13th-century Hungary. Even the 1298 laws prescribed that only Hungarian-born barons could hold positions and offices in the queen’s court.

(Source: Tarján M. Tamás / Rubicon Magazine, and Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Assassination_of_Gertrude_of_Merania)

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn