István V was born in 1239, the firstborn son of our epochal King Béla IV and a Byzantine princess, and reigned as King of Hungary between 1270 and 1272. In Hungarian historiography, he is a contradictory figure: on the one hand, he appears as an ungrateful, power-hungry son, and on the other, as a valiant soldier and a talented ruler with good organisational skills.

The seeds of discord

During the Mongol invasion, István and his parents took refuge in Dalmatia. Afterwards, his father had him crowned as a child and, sealing an alliance with the Cumans, who were desperately needed to protect the country in difficult times, he was betrothed to the daughter of the Prince of the Cumans. Their marriage later produced five daughters and two sons. In 1246, he was already mentioned as crowned king and prince of Slavonia.

In 1257, his father put the now adult prince at the head of Transylvania, but the following year he was already ruling the southern part of the new province of Styria, bordering Slavonia. After the Peace of Pozsony, an uprising broke out in 1258 in southern Styria, which belonged to Hungary. The Styrian uprising was suppressed by Béla IV, who placed his son István at the head of the province as Prince of Styria. At the end of 1259, the Styrians rebelled again and sided with the Bohemian king Ottokar II, leaving only Pettau and a few small castles in Hungarian hands.

The battle of Morvamező at Kroissenbrunn (one of many battles on that field) brought an end to Hungarian rule over Styria (1260). The ‘troubles’ began somewhere around here. The decisive battle, after the initial successes of István, seems to have ended in defeat because of a mistake by King Béla IV, who delayed the main army, and at the same time, István was wounded. All in all, István proved his mettle here, and the spark of discord was ignited. After the defeat at Morvamező, Béla IV put the still underage Prince Béla at the head of Slavonia and sent Prince István, who had proved his military prowess, back to Transylvania.

Despite this, István was still willing to cooperate with his father. In 1261, they again fought together in retaliation for the Bulgarian invasion of the previous year, defeating the Bulgarians near Vidin. This time, it was left to the prince to finish the job, who penetrated deep into enemy territory, winning victories on the right bank of the Danube and near Nicapolis on the River Isker.

By 1262, the two were already at arms, and the sources tell of a real (albeit brief) war, at the end of which a charter names István the younger king for the first time. The documents do not give any information on the reasons for the 1262 confrontation, but according to Kristó Gyula, it was basically the power of the aristocracy that was manifested in the constant and increasing conflict between the king and his first-born son.

At the Treaty of Pozsony in 1262, István was given full independent kingship of the eastern half of the country, as reflected in the new title he held from then until he became sovereign king in May 1270. This is confirmed by a letter of the Pope of 1263 from Béla IV, in which István was already called rex by his father. After 1262, the real leader of Hungarian Balkan policy was István with the title of the younger king.

In 1263, a Mongol invasion of the eastern frontier was reported to the Pope on 14 October. The border clashes did not develop into a major campaign because István – through his envoy – managed to persuade the Mongols to abandon their plans through diplomatic channels.

In the autumn of the same year, István launched his second Bulgarian campaign. The younger king’s troops were led by the Transylvanian voivode László of the Kán family and his brother Gyula. The campaign was conducted in north-western Bulgaria, under the protection of the Hungarian-backed ruler James of Sventzlavia, against the Byzantine emperor Michael Palaiologos and the Bulgarian tsar Constantine. István did not personally take part in the campaign, but the Hungarian army entered Byzantine territory through Bulgaria and was victorious.

In 1263, during the Hungarian internal war, Jakab Sventszláv, allied with his enemies, invaded the region of Szörénység and destroyed the whole of the province of István. It was only in the summer of 1266 that István was able to mount a retaliatory campaign. During the campaign, he won five major battles, captured the town of Bodony (Vidin), and on 23 June, he issued a charter for the town.

After taking Bodony, he advanced along the Danube to Plevna. After the capture of Plevna, his troops also took the castle of Vrachov, and his co-captain, Egyed, advanced as far as Turnov. Jakab was forced to surrender to István, and from this time onwards, the title “King of Bulgaria” became a standard title for Hungarian kings.

In 1268, another war broke out in the south, when the Serbian king Uroš I invaded the borderlands of the Kingdom of Hungary and destroyed the province of Prince Béla of Macsó. The army sent to defend the duchy, which belonged to the territory of Béla IV, was led by István of Csák (the Comes of Pozsony). The peace that followed the Hungarian victory was sealed with a dynastic marriage; Uroš’s son Dragutin married King István the Younger’s daughter Katalin.

In the last year of István the Younger’s reign, he prepared two more dynastic marriages. In the autumn of 1269, in Melfi, he concluded a double marriage and mutual aid treaty with King Charles I of Naples. The alliance was probably directed against Otto II. István opposed his father’s policy towards Otto II from the outset, but the possibility of an alliance with other members of the royal family cannot be ruled out. The marriage contract was for the marriage of his son, Prince László, to Princess Isabella of Anjou and his daughter Mária to Charles of Anjou.

The young “corex” (co-king) and the internal wars

According to Szabados György, the simultaneous, divided reigns of Béla IV and his son demonstrated a complete separation of sovereign power, which had not been evident during the previously “popular” father-son, or ruler-hereditary, rivalries. This was something new: István minted money, held the rank of Palatine (the second-highest aristocrat, who was allowed to govern in the king’s absence), and pursued an independent foreign policy.

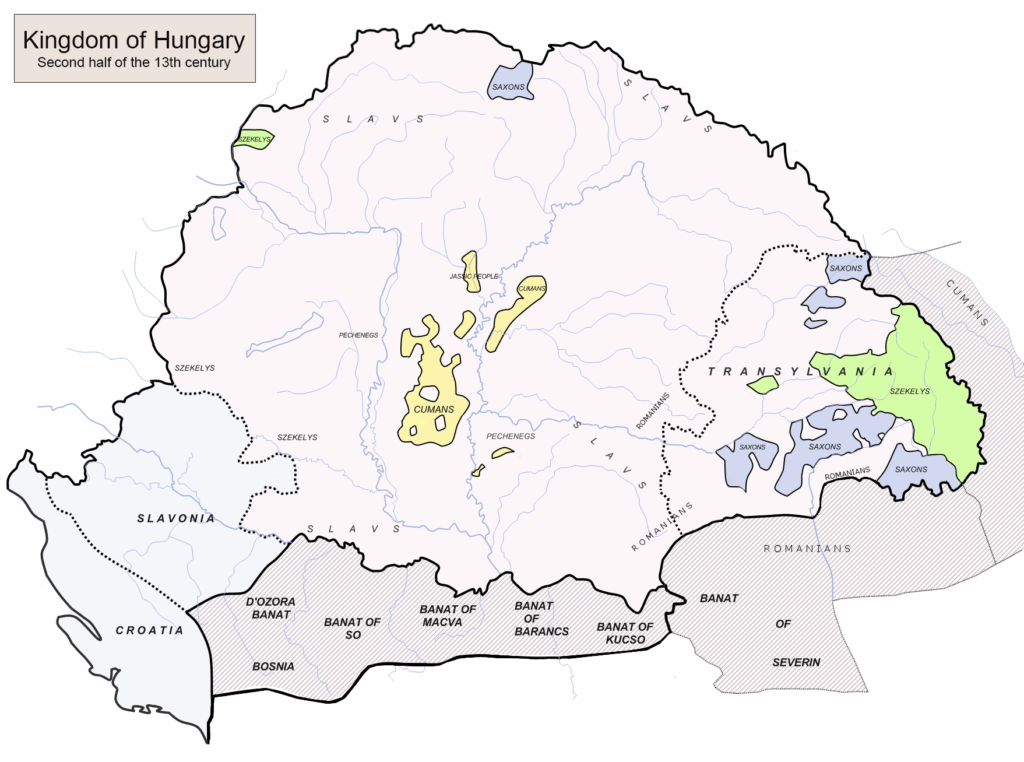

The institution and formation of the Younger Kingship is the subject of perennial historiographical debate, but one thing is certain: the greater part of the period of István’s de facto reign falls within the period of his Younger Kingship, when the country was divided into two parts and the Danube became the border between two independent kingdoms.

It is essential to note that the estates of Béla IV’s and István’s followers did not align with the dividing line, nor did the estates of some members of the royal family, which, of course, could also have been a source of tension. The younger king, by then preoccupied with foreign policy, probably considered the feud to be over with the division of the country. This is also indicated by the fact that on 5 October, he attended the wedding of his brother Béla and the Duchess of Brandenburg, Cunigunda, near Pozsony. By early December, however, he was forced to mobilise his forces. In the last month of 1264, two coordinated attacks were launched against the younger king’s part of the country.

A family feud

Around 10 December, the Hungarian-Cuman army of László and Gyula of the Kán clan, who had hitherto belonged to István’s entourage, entered the southern part of István’s territory, and advanced along the valley of the Maros to Déva, where the army, consisting mainly of Cumans, was defeated. In the north, the military of Henrik of the Heder family attacked from the direction of the Szepesség (Spiš) region, with the daughter of Béla IV, Anna, in the army.

However, the two-fronted attack must have taken István by surprise, as the clash with the Kán brothers had already taken place deep in the younger king’s part of the country, and his family was confined to the easily accessible Patak castle. The attackers captured Patak, the home of the younger king’s family, and took the younger king’s entire family (the younger queen Erzsébet, her daughters, and the two-year-old Prince László) prisoner. To relieve the northern part of the country, István sent the Csák brothers (Péter and Máté) north, while he retreated to the castle of Feketehalom.

Despite the success in Déva, the younger king found himself in a difficult situation. The distracting operation led by the Kán brothers, the Cuman army, was only the vanguard of a larger army led by Kemény’s son, the king’s judge Lőrinc. As a result of these events, István was abandoned by his supporters. Forced to split his army because of the northern theatre of operations, István and his most loyal followers could only rely on the defence of the castle of Feketehalom.

The army of Csák Péter arrived late to the north after the fall of Patak, achieved some successes in the conquered northern part of the country – recapturing the castle of Baranka in Bereg county – but could not undertake a decisive battle. The army of Kemény’s son Lőrinc, who was pursuing István from Déva, surrounded the castle of Feketehalom, and the attempts to drive him out proved ineffective. From the castle, which had become a “reservoir of death and misery”, István sent Demeter of the Rosd clan as a special envoy to his parents, but Demeter fell into the hands of Kemény’s son Lőrinc, who tortured and imprisoned him.

The success of the relief army, which returned from the north at the end of January, augmented by Saxons, was greatly aided by the actions of Panyit of the Miskolc clan, who was operating among the besiegers. The rescuing army and those who broke out of the castle, pinning the besiegers between two fires, defeated the besiegers, and Lőrinc, the son of Kemény, was taken prisoner by Ivan, the son of András.

Taking advantage of the success, the younger king, who was well-versed in warfare, went on the offensive. He led his army towards the centre of the country, defeating the Cuman army led by the Cuman leader Menk, and then the army led by Ernye bán (duke). In the battle, which was already fought in the Tiszántúl region, Ernye bán himself was taken prisoner. Béla IV was forced to give up the conquest of the Highland castles and retreated to secure the Pest ferry. Béla IV, in turn, took the underage Prince László to the more inaccessible Kraków.

The Battle of Isaszeg

The decisive battle took place near Isaseg (1265), where István won a complete victory, so that the fate of the country depended on his will.

King Béla IV concentrated his entire army on the battle, with the nominal commander-in-chief of the royal army being Prince Béla of Macsó. Queen Mária sent troops of a thousand men under the leadership of her minion, Henry Preussel, the rector of Buda. The decisive battle took place at the beginning of March, near Isaszeg. The royal army was led by the Palatine. The younger king personally led his troops and personally took part in the battle. He defeated an attacking knight in a duel, while his bodyguard, Drug’s son Sándor, protected him from the other attackers.

Prince Béla managed to escape from the battle. Palatine Henry was taken prisoner when he was struck to the ground by the spear of Rénold of the House of Básztély, and his two sons were also taken prisoner. The rector of Buda Castle, Henrik Preussel, who was also captured, was killed after the battle.

After the Battle of Isaszeg, peace negotiations lasting nearly a month began, mediated by the two archbishops. The agreement was recorded in a letter of 28 March 1265 from King Béla IV to Pope Clement IV, asking him to confirm the agreement and treaty with his son.

According to the text of the peace treaty, King Béla IV readmitted István to his fatherly love, who in turn assured his father of his sons’ respect and obedience. This all sounded very nice, but in reality, the deep-seated differences remained unresolved. The distrust did not, however, prevent them from launching a joint campaign against the Cumans who wished to leave the country, or the younger king’s part of the country – Béla IV’s relief army was led by Roland, a Slavonic Ban of the Rátót clan, who had stayed away from the internal war against István. The successful resolution of the Cumans’ case in the spring of 1266, however, led to a renewal of the conflict, as Roland, despite the successful campaign, lost the favour of his king.

The second coronation of István

István was crowned king a few days after the death of his father on 3 May 1270, before 13 May, by Fülöp, Archbishop of Esztergom of the Türje clan, in Fehérvár. In addition to the high priests and aristocrats, other nobles and royal servants were present at the ceremony, forming a ‘vast assembly’. The term refers to the fact that the coronation was a scandal: no other overlords appeared. Moreover, it was expensive: the Archbishop of Esztergom received the whole county of Esztergom as a donation in exchange for the ceremony.

After the coronation, almost all of the barons of King Béla IV disappeared from political life. Among his father’s supporters, there were many opponents. His sister Anna, seizing part of the country’s treasures (thesaurus regni nostri), fled to King Ottokar II of Bohemia, followed by many of her father’s supporters.

In his foreign policy, István sought to expand his federal system. At the end of August 1270, he made a pilgrimage to Krakow, to the tomb of St. Sanislo, and on this pretext contacted Prince Boleslav. He initially tried to settle his conflict with Otto II peacefully through negotiations. In mid-October 1270, the two rulers met in person on an island in the Danube near Pozsony and agreed on a two-year truce. The rebellious lords could not be settled by negotiations, so in November István sent the Comes of Zala against Hahót Miklos, who was staying in the castle of Pölöske.

However, the Comes of Zala and his brother were slaughtered by the rebels who broke out of the castle with the help of the Germans who had taken them in. The escalating Hungarian-Bohemian conflict soon led to war, which began with border skirmishes. By December, Hungarian troops were raiding Austria. In the week after Easter 1271, Ottokar crossed the Morava River and captured the castles of Pozsony, Szentgyörgy, Bazin, Vöröskő, and Nyitra, as well as the city of Nagyszombat.

Ottokar’s main force was the Czech, Moravian, Austrian, Styrian cavalry and the troops of Carinthia, Thuringia, Meissen, Brandenburg, and several Silesian duchies – also mainly heavy cavalry. The area north of the Danube to the Garam valley was under the control of the Czech-German forces within three weeks. The enemy crossed the Danube at Óvár on 9 May 1271 and then engaged the Hungarian main force at Moson before 15 May. Both battles ended in Hungarian defeat, so István withdrew his army behind the Rábca River.

After initial peace negotiations, a Hungarian detachment attacked Ottokar’s camp near Moson on 21 May and lured the moving enemy into the marshy countryside between the Fertő and Rábca rivers. The heavy cavalry was trapped in this terrain, and István drove the attackers back as far as Moson, who retreated to Pozsony the next day. In Pozsony, Ottokar dispersed his weary troops. The impetus for the end of the war came from raids by Hungarian light cavalry into Lower Austria and Moravia.

The parties concluded a peace treaty in Pozsony on 2 July 1271. Ottokar II renounced further support for the disloyal rebels, and King V. István renounced the treasures his sister had taken to Prague. The victory consolidated István’s position of power, and he began to implement his reform plans.

His reformation programme mainly developed the towns and villages with guest settlements. He raised Szatmár to the status of a town. He gave the city of Győr and probably also Kolozsvár the right granted to Fehérvár. He issued a comprehensive privilege for the Saxons of Szepesség (Spiš), and also granted the privileges of Aranyosmeggyes in Szatmár and Felszász in Ugocsa. In the meantime, he confirmed the privileges of the towns and guest settlements founded by his father.

He aimed to reorganise the structure of the court estates, with commissioners appointed with national powers to regulate the use of land and settle disputes over royal estates. He occasionally convened territorial assemblies on matters affecting the nobility. In Hajóhalm, Heves County, he held an assembly of the nobility of the eastern part of the country in the spirit of ‘serving justice’ and maintaining ‘law and order’.

His court is characterised by the traits of chivalry – personal glory (gloria), excellence through deed (claruere), personal virtue and courtly spirit (courtoise). His proven ability as a commander, his more generous donation policy than his father’s, and his closer relationship with the nobility raised high hopes.

In the late spring of 1272, King István and his entire court set off for Dalmatia to meet his ally, Charles of Anjou. On the way, he was struck by an unexpected blow: at the end of June, at Bihács, the ‘king of all Slavonia’, Gutkeled Joakim, kidnapped Prince László from his entourage and took him to the castle of Kapronca on the River Dráva. The army sent by the king besieged the castle without success. During the events, István fell seriously ill. Sensing his imminent death, he took himself to the Great Island and died there on 6 August 1272. He was buried in the Dominican monastery on Margaret Island, where his sister, St Margit (who died on 18 January 1270), was buried.

During the excavation of the remains of the monastery in the 20th century, a funerary crown was found on the evangelical side. The “Szabina” crown, found in 1938, is thought to have belonged to István V, who was buried here.

Sources: Hungarian Wikipedia, https://mandiner.hu/hirek/2022/08/v-istvan-kiraly-tortenelem

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfk