There is a stubborn misconception on the internet, mainly among the Romanian, Slovakian, and some Croatian fellows, that Hungary ceased to exist after 1526 as a sovereign kingdom and reappeared from thin air only in 1868. Croats also claim that after 1527, they were not under the Hungarian crown. And the Transylvanian Principality was a mere vassal state of the Ottomans…

It is a perfect example of how modern national narratives can reshape and simplify the past. A half-truth is a full lie, and it reflects the wishful thinking of some people. It appears to me that denying the existence of something is the best denial, far better than telling negative things about it. I often meet this misconception, so let us talk about it a bit more.

In the famous novel of Bulgakov, „The Master and Margareta”, the Soviet editor, Berlioz, scolded the young poet, Ivan. His point was that instead of writing negative things about Jesus Christ, Ivan should write that Jesus never existed. Here is the extract from the book, enjoy:

„The thing was that the editor had commissioned from the poet a long anti-religious poem for the next issue of his journal.

Ivan Nikolaevich had written this poem in a very short time, but unfortunately, the editor was not at all satisfied with it.

Homeless (*Ivan) had portrayed the main character of his poem – that is, Jesus – in very dark colors, but the whole poem, in the editor’s opinion, had to be written over again.

And so the editor was now giving the poet something of a lecture on Jesus, to underscore the poet’s essential error.

It is hard to say what precisely had let Ivan Nikolaevich down – the descriptive powers of his talent or a total unfamiliarity with the question he was writing about – but his Jesus came out, well, completely alive, the once-existing Jesus, though, true, a Jesus furnished with all negative features.

Now, Berlioz wanted to prove to the poet that the main thing was not how Jesus was, good or bad, but that this same Jesus, as a person, simply never existed in the world, and all the stories about him were mere fiction, the most ordinary mythology.”

The Core of the Misconception: What Does “Cease to Exist” Mean?

The argument that Hungary “ceased to exist” after 1526 rests on a very specific and modern definition of sovereignty: a unified, independent nation-state with a king ruling from its historic capital. By this strict definition, the Kingdom of Hungary was indeed profoundly transformed after the Battle of Mohács in 1526.

Before the defeat of Mohács in 1526, some of the Hungarian lords tried to make King Lajos (Louis) of Hungary understand that the Turks needed Vienna and not Hungary. Also, Sultan Suleiman would have agreed to get a safe corridor to the desired “Golden Apple” of Vienna. In case of opening a passage to the Turks, King Lajos could have kept his crown and inner autonomy without the destruction of his lands. He could have kept his army and laws in exchange for some lip service and annual taxes paid to the Sultan. (The Habsburgs later paid more annual “gift” to the Sultan in exchange for peace than Lajos would have ever paid.) A LOT better terms and conditions could have been given to Lajos compared to the later miserable conditions of Wallachia.

However, historians argue that the Hungarian kingdom did not vanish; rather, its political form changed dramatically. It continued to exist as a legal entity, but its territory was divided and its sovereignty became contested.

Part 1: The Fate of the Kingdom of Hungary after 1526

Remember how the Habsburgs helped Hungary before Mohács. Habsburg Ferdinand sent a few unusable cannons to his cousin, Lajos. Who dares say that he never thought of the eventual death of the Hungarian king? We know that the Battle of Mohács was a catastrophe, especially because of the death of King Lajos (Louis) II, and it created a power vacuum. What followed was a two-, later tripartite division that lasted for nearly 150 years.

1. The Ottoman Empire (Occupied Hungary):

The central part of the kingdom, including the capital Buda, was directly conquered and incorporated into the Ottoman Empire as the Budin Eyalet (and other provinces). This was not a Hungarian state; it was under direct Ottoman rule. It was only 41% of the Kingdom, though. Also, it has never been as smoothly integrated into the Ottoman Empire as the Balkan states because the old Hungarian feudal system was just too hard to break. The Ottomans heavily garrisoned their castles with mainly South-Slavic mercenaries, and in the 17th century, they were not safe to travel between their strongholds without a sizeable contingent of troops.

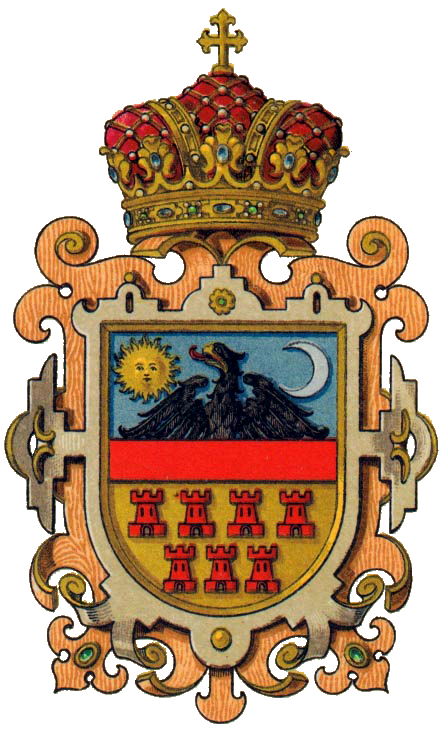

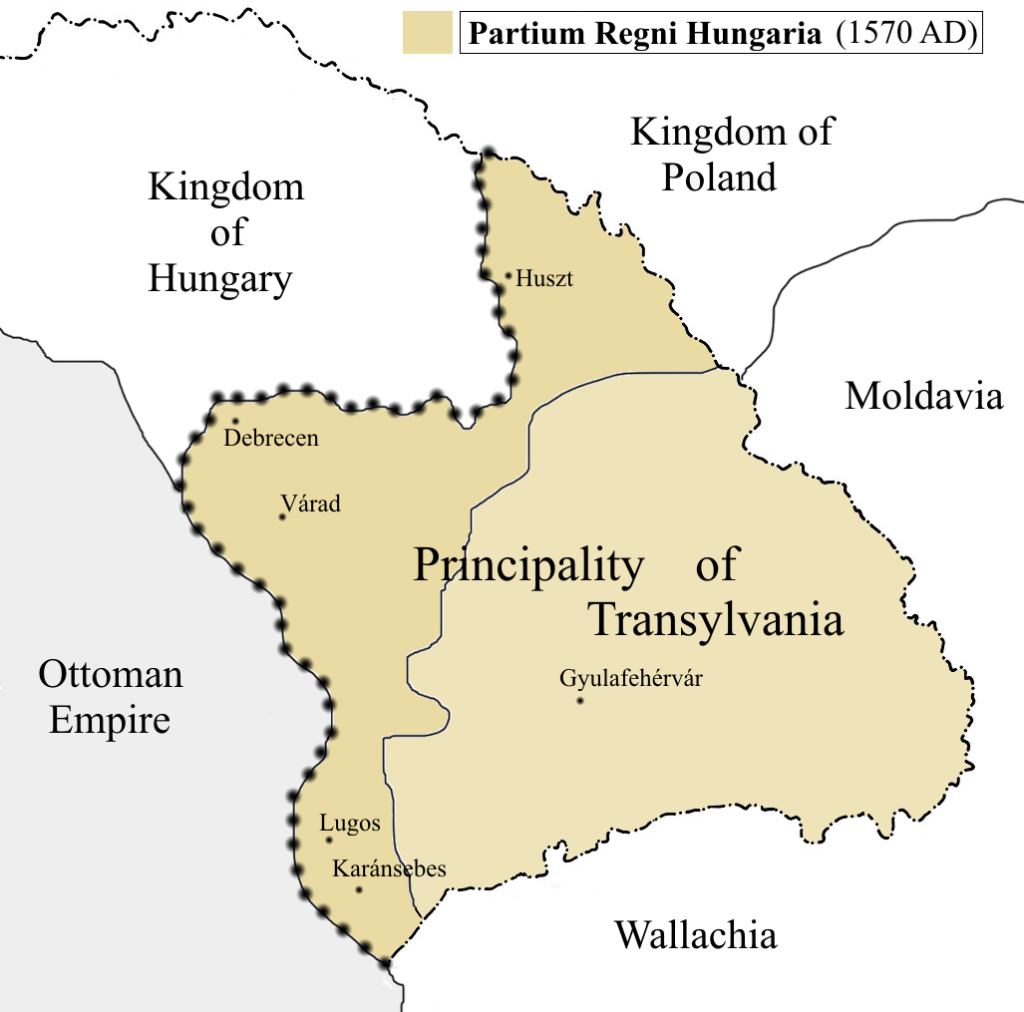

2. Some thoughts on the Eastern Hungarian Kingdom / Principality of Transylvania:

The eastern part, Transylvania, did not fall to the Ottomans. Note, the Turks were not as strong as one would think, and their goal was Vienna, the desired “Golden Apple”. Let us not forget that we are talking about a sizeable land in Central Europe: the area of the Principality was almost twice as large as the size of modern-day Hungary. Even the present area of Székely-land, the home of the Hungarian Székelys, is larger than modern Kosovo.

Szapolyai János used to be the Voivode of Transylvania under the reign of King Lajos. After Mohács, he was in charge of an intact Transylvanian army, and soon he was crowned King of Hungary. After the Habsburg attack in 1527, King Szapolyai was not supported by any Christian monarchs. With the help of his genius diplomat, the Polish Hieronym Łaski, Szapolyai was able to prevent the Ottomans’ general attack on Hungary. Having settled a treaty, Suleiman “allowed” him to be the king of East Hungary because the Sultan focused on Vienna and had not had enough troops to overrun East Hungary just yet.

In Eastern Hungary, the Hungarian Estates supported Szapolyai János as king. And not just a few of them: 95% of the nobles stood by him, while Habsburg Ferdinand had only a handful of Hungarian supporters at the time of his coronation. The kingdom was functioning again in 1527, but it had to face the Serbian Cerni Jovan uprising and the attack of Habsburg Ferdinand.

After a brief civil war with the Habsburg claimant, a unique situation emerged: Transylvania became an Ottoman vassal state, rather nominally. However, it was de facto a continuation of the Hungarian state under a Hungarian prince. Geographically speaking, Transylvania was stuck between the two empires, but luckily far away from them. The legal position of Transylvania was an action of volunteer acquiescence rather than an outcome of a conquest by the Turks. As Cardinal Pázmány Péter said in the 17th century: “We are the fingers between the door and the door-frame.”

It is worth noting that the Habsburgs tried to persuade Sultan Suleiman to cede Eastern Hungary to them instead of Szapolyai. This move, however, proved counterproductive. Its sole result was that subsequent Sultans officially referred to the Habsburg kings as mere “rulers of Western Hungary by the Padishah’s mercy”—a title that remained in use until 1606. This diplomatic fiction mirrored the reality that the Habsburgs frequently had to buy peace with substantial “gifts,” which were essentially tribute payments to the Porte.

It maintained Hungarian laws, a Hungarian diet, and a largely Hungarian administration. It became a center of Hungarian culture and resistance, often seen as the “keeper” of Hungarian sovereignty. All in all, the lands of East Hungary served as a basis for the Transylvanian Principality, which was not a vassal, for a vassal can be described like this:

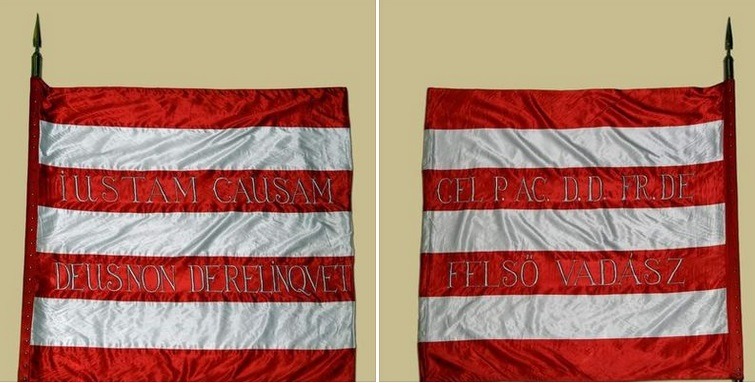

1. A vassal state does not have an independent foreign policy, but you can clearly see the foreign moves of the Transylvanian princes. When the Turks wanted to launch a war against the Poles in 1633 (as it happened in almost every decade), the Sultan ordered Rákóczi to come with his troops to Moldova and join them. Rákóczi was procrastinating, and it was finally he who negotiated with the Polish King Vladislav IV, telling him the Turks` plans and thus could block the war in 1634. Also, the Prince defeated the army of the Pasha of Buda in 1636 – an act of war, which was not punished either by the Sultan. One would think a real vassal would not have been allowed to scatter his overlord`s troops.

2. It pays taxes regularly. When Prince Rákóczi I György won the throne in 1630, we could see that he had been bargaining with the Sultan about the amount of the taxes for 5-6 years before paying a single coin to the Sublime Porte. It would have been unheard of and punished by a campaign immediately in the case of the two Wallachian states.

3. In war, it supports its overlord with troops and cannot elect its rulers. You can read more details about this in the article by Balla Péter: https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/transylvanian-principality-a-vassal-state-of-the-turks/.

As for sending troops to his overlord, the Sultan, two things must be mentioned: from the age of King Szapolyai to the reign of Prince Apafi, the Transylvanians have found millions of excuses for not giving troops to the Sultan against the Hungarians or the Habsburgs. It was more often, though, that the Transylvania princes borrowed Turkish units as auxiliary forces.

Also, Transylvania could even allow itself the freedom of not getting involved in the Ottoman-Austrian 15-Year-War on its overlord`s side. Yet, we see that the Transylvanian commander Bornemissza János (son of the valiant Bornemissza Gergely of Eger) was leading the Transylvanian forces in the Battle of Tura in 1594 against the Turks. Moreover, Prince Báthory Zsigmond had joined the Christian coalition against his overlord, the Sultan; it is true that he hurried back to Transylvania after the allied Christian forces were defeated in the Battle of Mezőkeresztes in 1596, but there was no punishing campaign launched against him after this.

At its absolute peak under Prince Bethlen Gábor (around 1620) and later Rákóczi György I, the sphere of control and direct military occupation of the Transylvanian Principality extended over approximately 200,000 to 220,000 square kilometers. This means the principality’s influence, for a short time, covered about two-thirds of the entire pre-1526 Kingdom of Hungary. At its peak, the Principality’s control extended far beyond its core ~55,000-60,000 sq km, briefly encompassing much of the northern and eastern parts of the former Kingdom of Hungary. The modern geographical region of Transylvania in Romania (including Bánát, Crișana, and Máramaros) is about 108,000 sq km.

The Ottomans provided military power both to Prince Bocskai István (whose statue can be seen in Geneva, next to Luther`s) and to Prince Bethlen Gábor, who made Transylvania rich and great. Bethlen had a role in 1617 to stop a Polish-Turkish war; it was the year when he refused the offer of the Swedes, who wanted to offer him the Polish crown.

He also refused the Hungarian crown from the Sultan`s hand (just like Bocskai did). He was playing with the idea of the unification of Transylvania, Wallachia, and Moldavia, thus establishing the „Kingdom of Dacia”. We have to remark that Bethlen was not fighting „directly” against the Hungarian Kingdom during the 30-Year-War but mostly against the Catholic coalition. Yet, Bethlen and Bocskai are dividing figures; many people either love or hate them.

Sadly, Prince Rákóczi II György overestimated his possibilities and thought Transylvania was strong as to get involved in the war for the Polish throne in 1657. It led to the decline of the „Fairy Garden” as Transylvania was called at that time, because the Turks, after several warnings, punished him and the Principality severely. Várad Castle (Oradea), the gate of Transylvania, fell in 1660 to the Turks after a heroic siege. Shamefully, the Habsburg Emperor didn`t allow his forces to help the castle, although his general was very close to the city with a large Imperial army.

Prince Apafi and his son, the next rulers of Transylvania, had to pay more taxes to the Sublime Porte even though Transylvania’s area had become smaller due to the loss of Várad castle. Yet, Apafi didn`t give troops to the Sultan in 1683 when he was attacking Vienna. Finally, it was the Diploma Leopoldium in 1690 which finished the independence of Transylvania, attaching it to the Habsburgs: yet, the last Prince of Transylvania was Rákóczi Ferenc II, who left the country in 1711.

Balla Péter concluded in his lecture that Transylvania was a country that had ties to both the Ottoman Empire and to the Habsburg-led Kingdom of Hungary; it was not sovereign, but it had its autonomy, it was not a vassal state, but it submitted itself to the Turks in a contract.

Wallachia and Moldavia

Wallachia and Moldavia were closer to the Turks and consequently, enjoyed many times lower privileges. Also, there were times when they were supervised by the Transylvanian Principality. The prince of Transylvania made a contract with the Sublime Porte, which was called an „athame,” and it was a superior contract to a pherman: for example, Aron, the Voivode of Moldova, was appointed by the Pasha of Silistia, who sent him just a pherman.

We can better understand Transylvania’s position if we compare it to the two Wallachian states, Moldova and Wallachia, which were more strictly supervised, and their rulers had to pay the taxes in person to the Sultan on a fixed date each year. In case they failed to do so, a punishing campaign was launched immediately. It was not so in Transylvania; the tax was smaller and sometimes not paid at all, and never by the prince in person. We can’t talk about a punishing campaign for not paying taxes.

Prince Báthory István (1533-1586), the later Polish king, had even the power to bargain with the Sultan. The Sultan sent him an athame first in 1572, and the Sultan requested him to pay the taxes at a fixed time in person. Báthory refused it, and the Sultan`s request was taken out from the next athame in 1575. Now, Báthory didn’t like another statement in it, which said he would be submitted under the Sultan just like the other vassals were. The Sultan finally had to send him the third athame without this statement in the same year.

This document already addressed Transylvania as an “empire,” and it looked like rather a contract between a Muslim and a Christian ruler, although indicating the superiority of the Sultan. This diplomatic success could enable Báthory to get involved in the Polish king’s election. He was able to persuade the Polish noblemen to elect him as their king with Turkish help: the Ottoman diplomats also told the Polish Estates plainly that this would be the only way to avoid a Polish-Ottoman war. In this case, we can also see that Transylvania had a lot bigger room to shape its foreign policy – to a certain extent, of course.

Transylvania was also given supremacy above the two Wallachian states by the Turks: when Voivode Aron of Moldova hanged some wealthy Jewish people, the Sultan sent there Prince Báthory Zsigmond in 1592 to tidy things up, which he did. Also, we know that Moldova and Wallachia had to send gifts not only to the Sultan but to the Transylvanian prince, too.

3. The Royal Hungary (Habsburg Rule):

The northern and western parts of the kingdom were secured by the Habsburgs, whose claim was based on a marriage treaty with the previous Hungarian dynasty. Ferdinand I was crowned King of Hungary. The territory of Western Hungary was approximately 100,000 to 120,000 square kilometers. This was only about one-third of the pre-1526 Kingdom of Hungary (which was roughly ~325,000 sq km). The territory of present-day Hungary is approximately 93,030 square kilometers.

The historical proof that the Habsburgs, especially in the century following the Battle of Mohács (1526), treated the Kingdom of Hungary as a sovereign state—despite their clear dynastic ambitions—is found in the legal and political compromises they were forced to make. Their need for Hungary’s economic and military strength to combat the Ottoman Empire compelled them to acknowledge and operate within the framework of the Hungarian constitutional monarchy.

The key evidence lies in the legal coronations, the Diet’s continued power, and the explicit terms of agreements between the Habsburg monarchs and the Hungarian estates.

This was the crucial point: The Habsburgs ruled Western Hungary not as Emperors of Austria, but as Kings of Hungary. The Hungarian Diet continued to function, Hungarian law remained in effect, and the administrative structure of the kingdom was preserved, albeit with heavy Habsburg influence. They were allowed to wear the Holy Crown of King Saint István under the condition of keeping the laws of the kingdom. Thus, they had to keep the customs and the administrations intact. Of course, they tried to swallow Hungary and turn it into their hereditary land, but they always failed to achieve it, unlike in Bohemia.

In other words, in the medieval Kingdom of Hungary, sovereignty did not reside solely in the person of the king but in the “Holy Crown of St. István,” a legal fiction representing the community of the realm, including the king and the estates (nobility). For a ruler to be the legitimate King of Hungary, a coronation with the Holy Crown in Székesfehérvár (and later in Pozsony/Pressburg, today’s Bratislava) by the Archbishop of Esztergom was mandatory. Without this, their decrees were not legally binding in Hungary.

The Coronation of Ferdinand I (1527): After the death of King Lajos II at Mohács, the Hungarian Diet was split. One faction elected Szapolyai János, while the other, fearing the Ottomans, elected the Habsburg Ferdinand I, who was the late king’s brother-in-law. Ferdinand did not simply claim the throne by right of inheritance or force. He had to convene a Diet, negotiate with the estates, and, crucially, be crowned according to Hungarian law in 1527. This act alone signifies that the Habsburgs had to recognize Hungary’s separate constitutional identity to claim its throne.

Pozsony (Pressburg, today’s Bratislava) became the new capital and coronation city for Hungarian kings. The Habsburgs accepted the existence of the Hungarian Kingdom and kept its constitution alive because they needed the Hungarian swords, and the enormous income from the mines and the cattle business.

The predominantly Hungarian Principality of Transylvania was also a threat to the Habsburgs: if the Habsburg kings were too aggressive with their Hungarian subjects, they just sided with the Hungarian prince of Transylvania. It is interesting enough, but the partition of Hungary had contributed to its survival: the noblemen in Royal Hungary could at any time blackmail the Habsburg rulers by threatening Vienna with joining the Transylvanians when they thought their constitutional privileges were in peril. The spread of Protestantism in Hungary was a sign of defiance, too. Remember the Transylvanian princes’ wars against the Habsburgs, and how easily the Hungarian lords sided with them, especially with Bethlen Gábor.

Following the failed Ottoman siege of Vienna (1683) and the subsequent Holy League campaigns that began liberating Ottoman-occupied Hungary, the Habsburgs were at the peak of their military power. Emperor Leopold I could have been tempted to annex Hungary by force. Instead, he negotiated with the Hungarian Diet.

The Law of 1687 (Article I): In this year, the Hungarian Diet voluntarily recognized the Habsburg right of hereditary succession in the male line. In return, Leopold I had to formally confirm the fundamental laws and privileges of the Kingdom, including the freedom of religion for the estates (a major point of contention). This was a quid pro quo. The Habsburgs gained a crucial dynastic security, but they had to reaffirm Hungary’s constitutional integrity and the Diet’s role as the guarantor of that constitution. This is the action of a sovereign state negotiating with its monarch, not a conquered province being dictated to.

The Diploma Leopoldinum: Instead of simply absorbing Transylvania into the Habsburg hereditary lands, Emperor Leopold I issued the Diploma Leopoldinum in 1691. This document formally incorporated Transylvania into the Habsburg Monarchy, but as a distinct entity under the Holy Crown of Hungary. It guaranteed Transylvania’s internal constitution, its Lutheran and Calvinist religions, and its administrative autonomy. This act demonstrates that even in a position of strength, the Habsburgs recognized the need to govern these lands according to their historic, sovereign laws and political structures.

After the Turks were driven out, the Habsburgs made a violent attempt to diminish the kingdom. The absolutist and anti-Protestant policies of Leopold I led to a massive war of independence led by Prince Rákóczi Ferenc II. The war ended not with a total Habsburg victory, but with a negotiated peace. The War of Independence of Prince Rákóczi Ferenc II between 1703 and 1711 obviously stopped the absolutist intentions.

The Peace of Szatmár (1711): This treaty was not a simple surrender. It was a contract between the Habsburg monarch and the Hungarian estates. In it, the new Emperor-King, Charles III (Charles VI), promised to:

- Respect the laws and constitution of Hungary.

- Govern Hungary through its own legitimate institutions (the Diet, the Council).

- Grant a general amnesty to all participants.

The Peace of Szatmár is perhaps the clearest proof. After a devastating eight-year war, the Habsburgs, who again needed Hungary’s stability and resources for the upcoming War of the Spanish Succession, chose to reaffirm the sovereign rights of the Kingdom of Hungary rather than impose absolute rule by force. This set the stage for the “neo-accommodation” of the 18th century, where the Hungarian nobility cooperated with the Habsburgs in exchange for the preservation of their constitution.

This relationship was famously summarized in the Latin motto attributed to the Hungarian estates: “Moriamur pro rege nostro” (“Let us die for our king”). The crucial, often unstated, second part was: “dummodo rex noster, pro nobis moriatur” (“provided that our king dies for us”). The Habsburgs needed Hungary’s strength, and in return, they were compelled to treat it as a sovereign partner in a personal union, not as a mere province.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848-49, which ended with brutal Habsburg suppression only achieved with Russian military intervention, stands as a stark, violent departure from the previous policy of negotiated co-existence, proving that the Habsburgs would only respect Hungarian sovereignty as long as it did not fundamentally challenge their imperial integrity and dynastic control. However, the Revolution in 1848-1849 was also a great lesson to the Habsburgs, so they were forced to restore many rights in 1867.

The Compromise of 1867 (the Ausgleich), which created the Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary, was the ultimate proof of this pragmatic necessity, as the Habsburgs, weakened by military defeat and domestic crisis, were forced to formally restore Hungary’s sovereign statehood and grant it complete internal self-government in exchange for its essential political and military cooperation.

Thus, the precedent of a sovereign Hungary, maintained through coronation oaths and diets, provided the essential legal and political foundation without which the 1867 Compromise would have lacked any historical basis. Unfortunately, the Habsburgs were not good masters of their country, and they dragged Hungary into WWI in 1914.

Conclusion on Hungary’s Sovereignty:

To say Hungary “ceased to exist” is incorrect from a legal and constitutional perspective. The Kingdom of Hungary, as a corporate entity with its own crown, laws, and diet, persisted in Royal Hungary. It was a sovereign kingdom in personal union with the Habsburg monarchy, meaning it shared a monarch but was a separate state. The idea of the “Holy Crown of St. Stephen” and the integrity of the “Lands of the Crown of St. Stephen” remained a powerful legal fiction throughout this period, which would be invoked during the 1848 revolution and the 1867 Compromise.

Part 2: The Croatian Claim: “Not Under the Hungarian Crown”

This Croatian claim is more nuanced and has a stronger legal-historical basis than the claim about Hungary’s total disappearance.

The Historical Background:

Since 1102, Croatia had been in a personal union with Hungary, governed by a Hungarian-appointed Ban (Viceroy), but with its own Sabor (parliament) and a degree of autonomy, according to the tradition of the Pacta Conventa. This meant that the Croatian estates recognized the Hungarian king as their own king, but retained certain autonomy (their own Ban, separate assemblies).

The Event of 1527:

Facing the Ottoman advance after Mohács, the Croatian Sabor met at Cetin and, feeling abandoned by the Hungarian nobility, elected Ferdinand I of Habsburg as their king. This was a separate act from the Hungarian coronation. Legally, Croatia entered the Habsburg–Hungarian arrangement as part of the Hungarian Crown. However, the Croatian estates always emphasized that they were not a mere province but a kingdom with historical rights.

In practice, during the 16th–17th centuries, most of Croatia fell under Ottoman rule, with only a small remnant surviving, often called the reliquiae reliquiarum (“the remains of the remains”). Nevertheless, the Croats preserved their political status and consistently claimed that they were a separate kingdom, albeit under the Hungarian Crown.

The Core of the Croatian Argument:

Croatians argue that by electing Ferdinand directly, they entered into a separate contract with the Habsburg dynasty. They were now under the Habsburg crown directly, not through the Hungarian crown. In their view, the personal union with Hungary was severed.

The Hungarian & Habsburg Perspective:

The Habsburgs and the Hungarian diet never formally accepted this interpretation. Administratively, for the Habsburgs, Croatia remained bundled with the Kingdom of Hungary as part of the “Lands of the Crown of St. István” for governance purposes. The Hungarian king was still the overlord of Croatia.

The Croatian Ban was often appointed by the Habsburg king, but the Hungarian diet frequently tried to influence this appointment.

Conclusion on Croatia’s Status:

This is a classic case of a historical “grey area.”

Croatian View: The act of 1527 was a realunion (a new union) with Austria, ending the subordination to Hungary.

Hungarian View: It was a change of monarch within the existing framework of the Hungarian Crown, and Croatia remained a part of the Crown’s lands.

Historical Reality: The Habsburgs, as pragmatists, often played both sides. In practice, Croatia maintained its autonomy (Sabor, Ban) but was consistently treated by Vienna as part of the Hungarian political complex until the 19th century. The Croatian claim is not a modern fabrication; it is based on a genuine historical event and a long-standing constitutional argument. In summary:

Hungary = a sovereign kingdom in personal union with the Habsburgs.

Croatia = a sovereign kingdom in personal union with Hungary, and therefore indirectly with the Habsburg ruler. So the Croats essentially had a “double personal union”: 1. With the Hungarian king (since 1102). 2. Once the Hungarian king was a Habsburg, indirectly through the Habsburg dynasty.

Why All These “Misconcepts” Persist?

Nationalist Historiography: Both Hungarian and neighboring national histories were written in the 19th and 20th centuries to bolster claims to sovereignty, territory, and cultural prestige. For Hungarians, emphasizing the continuous existence of the kingdom justifies the pre-Trianon borders. For Croatians, Romanians, and Slovaks, emphasizing a break or a separate legal status undermines Hungarian historical claims and justifies their own independence.

- Simplification: The complex reality of divided sovereignty, personal unions, and feudal law is hard to reconcile with the modern “nation-state” model. It’s easier to say “Hungary disappeared” or “Croatia left the union” than to explain the nuanced constitutional reality of the Habsburg Empire.

- The 1867 Compromise: The creation of the Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy re-established a fully sovereign Hungarian state with control over its internal affairs. To outsiders, this can look like a “reappearance from thin air,” when in fact it was the culmination of a long process of the Hungarian political nation reasserting the sovereignty it had legally claimed all along.

In short, the Hungarian kingdom did not disappear but entered a long period of divided and limited sovereignty. The Croatian position is a historically grounded legal argument that was consistently opposed by the Hungarian political class. The internet arguments are modern, simplified echoes of these centuries-old constitutional debates.

The 20th-century partition of the country, a direct and tragic consequence of those centuries of conflict, is a story for another day. And I promise you, it will not be left unaddressed.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn