If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon:

Who I Am and My Mission

First and foremost, I am a Hungarian who trusts in God. While I am not a historian by formal academic training—my college degree is in a different faculty—my journey has been shaped by a different kind of education: a deep connection to the land and people of Central Europe, forged through extensive travels. This connection revealed to me that the love for one’s homeland is the most essential foothold from which to understand its past.

I have undertaken a mission to bring the Hungarian narrative of our grand and heroic history to the English-speaking world. Why? Because the truth must be told. If we do not tell our own story, others who are not our friends will tell it for us. Across social media, there are scores of English-language narratives hostile to Hungary, backed by prevailing trends and significant funding. Who is there to contradict them?

You might rightly ask: Where are the degreed historians? Where are the hundreds of others who are more educated, cleverer, and possess silver tongues? They may have high connections or work for institutions whose very job it is to represent Hungarian history. Yet, when I looked for them on the front lines of modern discourse—on social media—I found none.

So, I set out alone. From scratch, I began the work of disseminating Hungarian history. It is a mission that now, in 2025, organically reaches 1.7 million people every month.

Where My Approach to History Comes From

My work has been labeled “nationalist,” mainly by readers from Hungary’s neighboring countries. Yet, for some Hungarian readers, I am not nationalist enough. To be criticized from opposite extremes is, in its own way, a validation that one is likely walking a more nuanced path.

I reject the false choice between a “politically correct” narrative that sanitizes the past and an “ethnomaniac” one that distorts it for nationalistic purposes. The former is a form of intellectual hypocrisy, while the latter is a betrayal of genuine historical inquiry. I stand firmly against blatant generalizations and double standards.

My goal is to transcend these labels altogether. I believe history is not a weapon to be wielded in modern culture wars, but a complex tapestry to be understood. Hungarian history is not a threat; it is an asset. And it claims its proper place on the pages of world history.

My Father’s Roots: A Legacy Etched in the Landscape

My late father, Szántai Lajos, was from Salgótarján and was of Slovak descent. I often wonder if he knew the Slovak language himself, but unfortunately, he never spoke it to me. His parents were good, kind people, and I have always regretted that they left this world too soon.

At some point, our family name was changed from Sztrázska to Szántai. I do not know if this was by choice or by force. What I do know is that “Sztrázska” derives from the Hungarian word strázsa, meaning “guard.” This meaning took on a profound, personal significance during my childhood. When I was about twelve, my father took me to Salgó Castle, high above Salgótarján. He showed me the breathtaking view of Somoskő Castle, bathed in a white cloud, facing us from what is now the Slovak side of the border.

Years later, I made a discovery that connected our name to that very vista. Between Salgó and Somoskő castles lies a small hill named Strázsa Hill. It served as a watchpoint during the Ottoman era, a sentinel between two fortresses, much like the border that exists there today. The guard posted on that hill to watch for enemy raiders would have been called a strázsa or sztrázska. It is deeply moving to think that man could have been my father’s ancestor.

This sense of honor and connection to their home defined my grandparents’ lives. After WWII, when Czechoslovakia was reestablished, a propaganda campaign targeted Slovaks living in Hungary, including my father’s family, enticing them to relocate with offers of land and property freshly confiscated from deported Hungarians and Germans.

But my grandparents, Ferenc and Irén, were people of profound decency and integrity. They refused to build their lives in stolen homes. My grandfather, Ferenc, continued his honest work at the glass factory in Salgótarján. He had married my grandmother, Szurek Irén, from the small town of Nyustya (Hnúšťa). They likely met there, as the local iron smelter, part of the Rimamurányi-Salgótarjáni Ironworks, would have offered employment for a young man from the Salgótarján region.

To sum up, I would never deny my Slovak ancestry. It is an integral thread in the fabric of who I am.

My Mother’s Heritage: A Thousand Years in the Land

On my mother’s side, I am descended from Hungarians whose roots in the Northern Hungarian lands—modern-day Slovakia—stretch back to the 13th century. Our family’s documented history begins in 1249, when my ancestor, Hercsuth Tamás, was ennobled by King Béla IV and granted the village of Bélaszállás (Bella). Over the centuries, the family grew in stature, acquiring the villages of Ocskó and Lehota in Turóc County. By the turn of the 17th century, a Hercsuth served as the captain of Szklabinya Castle (Sklabiňa), a guardian of the realm.

Though the family’s fortunes had waned by the late 19th century, their legacy of leadership and culture persisted. My grandfather, Hercsuth Tibor, born in 1910, was a man of discipline and talent. He studied to become a conductor and earned the title of Champion of the Felvidék (Upper Lands) in athletics, winning a medal in the tournament. He later became the schoolmaster in the small village of Kálosa in Gömör County, where he married my grandmother, Katona Judit, a Hungarian girl from the nearby village of Felsővály (Vysné Valice).

His nobility of spirit was proven not only in peace but in war. As I have detailed elsewhere on my page, he performed a miracle of survival and loyalty during World War II, carrying a wounded comrade on his back during the brutal retreat from the Bend of the Don River in 1943, thus saving his unit at the same time. This very act of heroism would, in a twist of fate, indirectly save my mother’s life years later.

His commitment to his people was tested again after the war. In 1946, when Czechoslovakia was reestablished, he resisted the state-sponsored campaign of forced Slovakization. For this act of defiance, his property was confiscated, and his family was forcibly deported to within the new borders of Hungary.

As a child, I spent my school vacations in Czechoslovakia (1974-1990), visiting my relatives in Vály. There, I saw for myself how the local Hungarian minority was treated, and how their basic rights to use their native language and heritage were restricted. This experience had the greatest impact on me and profoundly shaped my thinking.

Forged in Resistance: My Political Awakening

The 1970s and 80s were a time of intense nationalist-socialist policies in Romania (hardcore) and Czechoslovakia (softcore). Yet, in Hungary, public discussion of these ethnic issues was largely taboo. I, however, refused to remain silent.

My political awakening began early. Between 1980 and 1984, I was a vocal and troublesome student at the Kafka Margit High School, actively opposing the regime. I participated in illegal demonstrations and was part of an underground group that challenged the Communist system. I later confirmed, from my file in the National Archives, what I had long suspected: the Secret Service had been monitoring me since 1981.

My activities culminated in 1984, when the entire board of teachers was convened to decide on my expulsion—not just from my school, but from all high schools in Budapest. I was saved by the courage of one teacher, Beke Kata, the same woman who had earlier entrusted me with the true story of the 1956 Revolution.

My academic background is from the ELTE Teacher Training College in Budapest, with a focus on Hungarian Literature and Public Education—a field dedicated to community building and the preservation of culture. During my college years, my focus shifted to Transylvania. I traveled there extensively, witnessing the darkest years of Ceaușescu’s nationalist-socialist Romania. I was deeply shocked by the systemic oppression inflicted upon the indigenous Hungarian communities.

I risked permanent exile from Romania to smuggle in food, Hungarian books, and medicine—a small act of defiance in an era when the state turned Hungarian Bibles into toilet paper. This cultural destruction was carried out with the silent complicity and active collaboration of the Kádár-led Hungarian government, which chose to betray its own people across the border, punishing any of us who dared to speak out.

My frequent travels to Transylvania forced me to learn Romanian out of sheer necessity. At the time, Hungarian visitors were strictly forbidden from staying overnight in the homes of Romanian citizens. To protect my Transylvanian hosts, who risked their entire livelihood by offering me shelter, I had to blend in. This small act of linguistic disguise was a matter of their safety.

Yet, these frequent travels held a crucial lesson. As time went by, my little knowledge of the language made me realize that the simple Romanian people are not our enemies. The conflict was engineered by a brutal regime, not born from innate hatred.

This period was so dense with action and revelation that it could fill a book. It was the fiery crucible in which my resolve was hardened and my perspective was forged—a perspective that learned to distinguish between a political system and the people it controls.

Following my graduation, I channeled my experiences into a concrete educational project. I developed a concept for a network of teacher training schools for Hungarian national minorities in Slovakia, Romania, and Ukraine, and presented it to the Youth Democratic Forum (IDF). As the first political youth organization formed after Hungary’s regime change, they welcomed the idea.

As one of the greatest and most urgent problems facing our communities abroad was the crisis in Hungarian-language education, the project immediately resonated across the political spectrum. It received scores of letters of support from politicians, organizations, and individuals alike, as this issue stood above political differences and demanded unanimous action.

We established a foundation and a team, and I was sent to a conference at the European Parliament in Strasbourg to seek international support. The project, which we named the “People’s Academy for Minorities,” was inspired by the Scandinavian “folk high school” model, where students contribute to self-funding through practical work. Politically, our vision was to shield these institutions from local governmental pressures by establishing a direct link to international bodies like the EU and the UN. Our foundation was built on the principles of equal human rights, democracy, and mutual respect.

Shortly after launching the foundation, I received a scholarship to continue my work and studies in the U.S.A.

It took months of determined effort to convince my American professors of the project’s credibility and remarkable potential. Their eventual endorsement led to the founding of an international NGO: the C.E.A.M. (Central and Eastern European Academy for Minorities).

One of our goals was to dispel ignorance and hatred between ethnic groups by spreading knowledge and conflict resolution so that the nations of the region could unite and work together peacefully. We were against manipulative political instigators who always wanted to use ethnic tensions to increase their power.

This international backing provided a crucial layer of credibility with Hungarian emigrant organizations in the U.S., who were often justifiably wary of initiatives originating from Hungary. Having finally earned their trust, I returned to Hungary for a major conference of the World Federation of Hungarians. There, I had high hopes to reap the harvest of our hard work: securing the financial support needed to launch the first two schools in Slovakia and Ukraine.

The final proposal, now enjoying the full support of the emigrant organizations, was ready for submission. However, on the eve of presenting it to the leadership of the World Federation of Hungarians (MVSz), I was forced to make an impossible choice. I had uncovered undeniable evidence of fraudulent activities within our own foundation’s office in Budapest.

Faced with this corruption, I could not, in good conscience, hand over the proposal. To do so would have betrayed the trust of our supporters and legitimized a corrupt structure. Consequently, the dream of creating an independent network of Hungarian higher education collapsed. I withdrew from the project entirely and never returned to the U.S., closing a chapter built on hope but undermined by deceit.

After the project’s collapse, I rebuilt my life. I married a Hungarian woman from a family also deported from Romania, and found stability as a teacher in Budapest. It took me years to overcome the failure of my ambitions, slowly channeling that drive into new purposes.

Yet, my passion for history never dimmed. I channeled my energy into deep reading and research. Then, in 2012, I took a step from theory into practice, beginning my journey in longsword fencing. I hope to continue this pursuit of Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA) for as long as I can still lift a sword.

The Unheard Hungarian Story

The Hungarian struggle against the Ottoman Empire is one of history’s most underrepresented chapters. In global education and popular media—from documentaries to films—the narratives of Austrians, Serbs, Romanians, and Turks are prominently featured, each claiming their role and honor.

Yet, the Hungarian voice is conspicuously absent from this conversation. While academic papers exist, the public story remains untold on social media.

This glaring omission is why I started my Facebook page, now called “Hungarian History”. My mission is to place the Hungarian narrative—our immense sacrifice, our resilience, our story—rightfully on the map of the world’s collective memory.

My Mission: Reclaiming Hungary’s Narrative:

In 2016, a stark realization ignited my purpose: the profound and heroic history of Hungary was virtually absent from the global conversation on social media. My work was born from a need to restore this vital chapter to its rightful place in the world’s general knowledge.

I believe that God’s gift of national diversity to mankind is a beautiful and intentional design. Taking pride in our national heritage is not just acceptable—it is good, provided it never serves as a pretext to harm others.

Through my deep study of history, I’ve learned that in the context of Central Europe, the bonds of national identity were often forged by a shared love for the homeland itself—a force sometimes more powerful than a common language. The second pillar of this identity was religion. Language and cultural heritage, while profoundly important, formed the subsequent layers of this foundation.

This understanding guides my work: to share the Hungarian narrative not as a weapon, but as a unique and invaluable contribution to the rich tapestry of human history.

A Personal Discovery: The DNA That Confirms a Lifetime’s Journey

After a lifetime of studying the interconnected history of Central Europe and championing a narrative that includes all its peoples, I received a personal revelation that brought this story full circle. I took an AncestryDNA test, and the results provided a scientific echo of the history I have dedicated my life to sharing.

I’ve always known who I am: a Hungarian, with a Slovak father and a rich family history on my mother’s side that I could trace back for generations. Or so I thought.

Recently, I had the chance to take an AncestryDNA test. I expected the results to simply confirm what I already knew. Instead, they opened a door to a more complex, interconnected, and surprising past than I ever imagined.

The Family I Knew

On my mother’s side, the Hercsuth name carries weight, as I had mentioned. The Hercsuth lineage dates back to 1249, when they were ennobled by King Béla IV of Hungary. This noble line, with its centuries of history in the region, undoubtedly infused our blood with German and Moravian genes from the various tides of European history.

My grandfather, Hercsuth Tibor, married my grandmother, Katona Judit, a woman of pure Hungarian descent from the isolated ethnic island of Felsővály in Gömör County. With this union, my Hungarian heritage seemed to be an unequivocal story, firmly rooted in the heart of the Magyars.

A Physical Mystery: The Árpád Dynasty Signature

But there was always a physical mystery in my family, one that felt like a whisper from the distant past. I was born with polydactyly—a sixth finger on my right hand. My mother was born with an extra tooth. This pairing of traits, a double genetic signature alternating between male and female relatives, is not just a random occurrence. Historians and geneticists note this specific combination as a rare, documented hereditary trait within the Árpád Dynasty, the very founding royal house of Hungary that ruled for over 400 years. Could the Hercsuth line have anything to do with them? Possibly nothing, but it is intriguing, nevertheless.

The Shock of the DNA Results

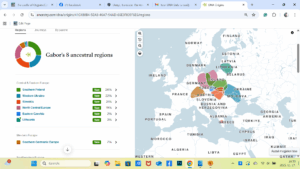

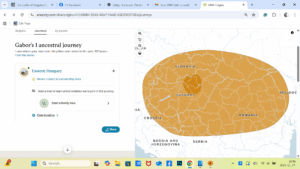

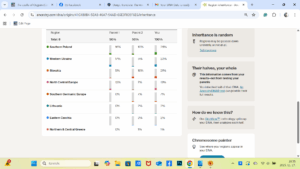

When my AncestryDNA results arrived, they didn’t say “Hungarian” or “Slovak.” Instead, they spoke in the language of ancient populations and genetic communities. My map lit up with a constellation across Central and Eastern Europe.

There it was: a primary connection to Central & Eastern Europe, with specific regions in Slovakia (a nod to my father), Eastern Czechia, and Southern Poland. But the biggest surprise? Significant connections to Poland and Lithuania. I was prepared for the Hungarian, the German, the Moravian, and the Slovak. But these new connections were hidden chapters of my family history, completely unknown to me.

The Cousin from America: A Living Link

Then came the most human part of the journey. Ancestry connected me with a cousin from America, Terry Lengyel. The surname itself was a clue—”Lengyel” is the Hungarian word for “Polish.”

Terry didn’t just share a family tree; he shared a face. He sent me a photograph of another cousin from the Lengyel line. The man in the photo, bearing a name that pointed to my mysterious Polish connection, looked exactly like I did in my 20s. It was an uncanny, breathtaking moment. A stranger from across the ocean, connected by a hidden thread of DNA, was my mirror image. It was no longer just about percentages on a chart; it was a living, breathing family.

Where Does the Trail Lead?

The “Eastern Hungary” genetic community, pinpointing Heves County, confirms my deep Hungarian roots from my grandmother’s side. The high Slovak percentage aligns perfectly with my father’s heritage.

The Polish and Lithuanian DNA is the legacy of a migratory past—the story of the Hercsuth family and countless other ancestors who moved across the map of Central Europe through marriages and alliances over 800 years.

My journey taught me that identity is not a single thread, but a tapestry. I am Hungarian, yes. But I am also Slovak, a little German, a touch Moravian, and surprisingly, Polish and Lithuanian.

This was the final, personal piece of the puzzle. It is no longer just a historical study for me; it is my genetic inheritance. The story I tell is not just Hungary’s story—it is quite literally, my own.

A quick look at my work in 2025

As a dedicated history digital content creator, 2025 has been a landmark year of growth and connection for my mission to share Hungarian history with a global audience. My digital platforms have collectively evolved into a thriving ecosystem, reaching and educating hundreds of thousands of people every month.

The cornerstone of this effort, my Facebook page ‘Hungarian History,’ now empowers a community of over 55,000 followers. In recent months, the page’s content has achieved a staggering 1.7 million monthly views, a testament to the public’s growing appetite for well-researched historical narrative.

This reach is amplified by two specialized communities: the ‘Hungarian History And Culture Without Borders’ group, which is rapidly approaching 20,000 members, and the ‘Hungarian-Ottoman Wars’ group. Together, these spaces foster deep discussion and engagement among nearly 41,000 dedicated enthusiasts.

Beyond social media, the heart of my work remains my self-hosted website, www.hungarianottomanwars.com, which now hosts a monumental archive of over 1,060 articles and has been viewed more than 260,000 times. Complementing this is my widely used Google Map, a unique digital resource charting 416 fortifications and churches, which has guided history lovers to nearly 400,000 views.

A particularly exciting development in 2025 has been the rapid adoption of my ‘Hungarian History Podcast’. Since its launch in April, listenership has seen explosive growth, with 6,000 downloads altogether on different platforms. This foray into audio storytelling has opened a new channel to engage with a global audience.

My work attracts a diverse community—Turks, Germans, Slovaks, Romanians, and others—including some who serve as my Admins. This is no accident. History in our region was often shaped by alliances that transcended modern national labels.

Our Facebook group is living proof that constructive dialogue is possible. We tackle sensitive historical issues, and while debates are vigorous, we resolve them through respect. I strictly enforce this environment: any comment that hurts, humiliates, or despises others is deleted immediately. My Facebook page, which reaches millions, fills a historical knowledge gap, but it will never be a playground for haters.

To ensure clarity and inclusivity, I always provide both the Hungarian and contemporary names for towns and castles. My goal is a shared space for mutual appreciation, focused on improving our common historical narrative—without modern politics.

My website celebrates heroism in all its forms. Alongside stories of Hungarians, you will find accounts of heroic Slovaks, Serbs, Germans, Irish, and Turks. I detail how King Matthias Corvinus knighted his Jewish subjects, chronicle the times Hungarians fought each other, and share a legend of the Roma defenders of Nagyida Castle. I am also dedicated to preserving the often-overlooked deeds of history’s courageous women.

As for my perspective, I make no claim to detached, ivory-tower objectivity. I am a Hungarian, and my narrative is one of clear-eyed pride—a pride that acknowledges both the glorious and the inglorious in our past. A key, demonstrable fact of that past is the immense price paid by Hungarians—and, I acknowledge, the peoples of the Balkans—in defending Europe against Ottoman expansion. My mission is to tell this complex story with honesty and respect for all who shaped it.

If you feel compelled to support this work, your help is most welcome. Sharing our content is invaluable. If you wish to contribute more directly and help keep the inspiration flowing, you can always buy me a coffee:

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

I’d like to draw your attention to the books I’ve written. You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital; they are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X

or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts. You might find a few interesting items in my Shop:

https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/shop/

All suggestions, donations, prayers, and connections are most welcome. I will not give up, no matter what. I am grateful to my wife for her kind support and encouragement.

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon:

Become a Patron!Send me a one-time donation via PayPal or "Buy me a Coffee":

Thank you very much, köszönöm szépen.