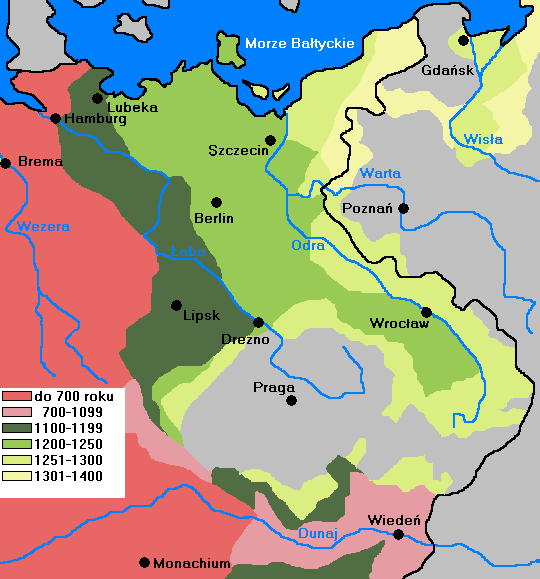

, Glaser Lajos

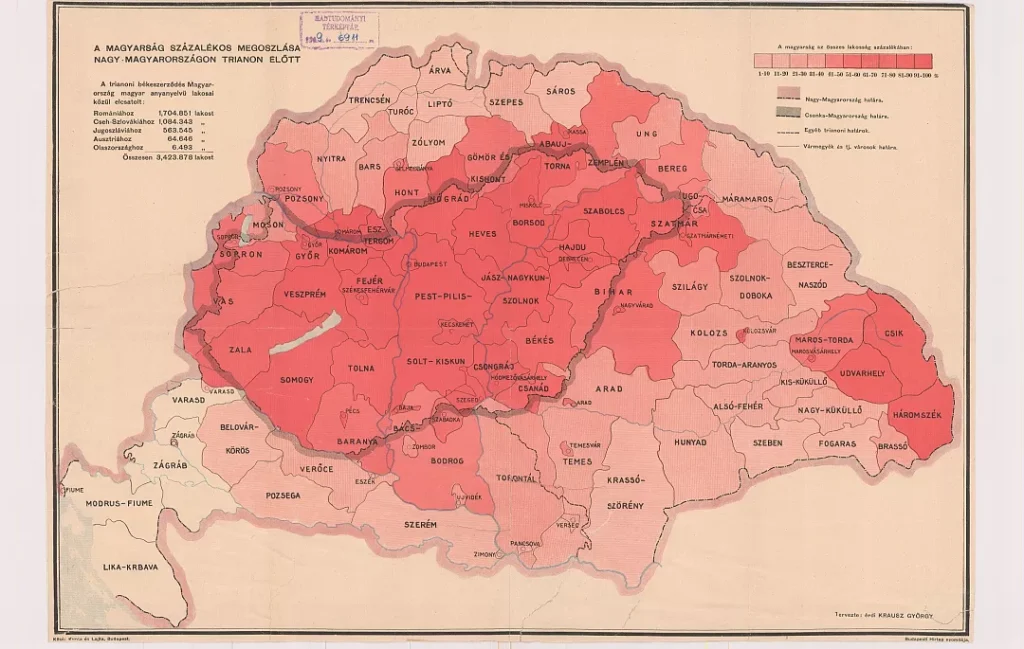

, Glaser Lajos ). A note on this map: A modern reconstruction of ethnolinguistic groups in the 11th century, based on the theories of Kniezsa István (c. 1941). It is important to note that this map is a scholarly hypothesis from the mid-20th century. Modern historiography treats such precise ethnic mapping with caution, as data is scarce and contemporary identities were more fluid and less territorially fixed than the map suggests. It is used here for illustrative purposes to give a general impression of diversity, not as a definitive demographic statement.

). A note on this map: A modern reconstruction of ethnolinguistic groups in the 11th century, based on the theories of Kniezsa István (c. 1941). It is important to note that this map is a scholarly hypothesis from the mid-20th century. Modern historiography treats such precise ethnic mapping with caution, as data is scarce and contemporary identities were more fluid and less territorially fixed than the map suggests. It is used here for illustrative purposes to give a general impression of diversity, not as a definitive demographic statement.In this series, I would like to explore one of the most fascinating aspects of our history: how the Kingdom of Hungary, and later the Principality of Transylvania, managed a remarkable diversity of ethnic groups. Rather than seeking to impose uniformity, the state often developed a system of pacts and privileges that turned diversity into a source of strength, ensuring stability and mutual benefit for centuries.

But to truly appreciate the uniqueness of this system, we must first glance at the world around it. What was the norm in contemporary Europe?

The European Standard: A Spectrum of Coexistence and Conflict

In the High and Late Middle Ages, the prevailing model of state-building in Western Europe was one of centralization and cultural homogenization. The ideal was a unified realm under one king, one faith, and one law. However, a closer look reveals a complex spectrum, against which Hungary’s model becomes even more distinct.

The Byzantine Empire: Hierarchical Integration. The Byzantine Empire managed a vast array of ethnicities—Greeks, Slavs, Armenians, Vlachs, and others. Its approach was one of centralized, hierarchical integration. The goal was to incorporate elites into the sophisticated imperial bureaucracy and military, and to assimilate populations into the Orthodox Christian and Hellenistic cultural sphere. While often pragmatic, it did not grant the kind of formal, legal autonomy seen in Hungary. Diversity was managed from the top down within a single, rigid imperial structure.

France: The Engine of Assimilation. The French monarchy, from its power base in Île-de-France, waged a long campaign to bring its outlying regions—Brittany, Occitania, and Burgundy—under direct control. The Albigensian Crusade (1209-1229) against the Cathar “heretics” of the south was as much a war of cultural and political conquest as a religious one. The goal was to erase regional identities and integrate them into a growing “French” identity dictated by Paris.

England: Conquest and Subjugation. After the Norman Conquest of 1066, the Anglo-Saxon population was relegated to second-class status. The new Norman elite monopolized land and power. This pattern of conquest continued in the Celtic fringes. The conquest of Wales was finalized in the 13th century, and English dominion over Ireland was marked by the Statutes of Kilkenny (1366), which explicitly forbade the English settlers from adopting the Irish language, customs, and law—a clear attempt to prevent assimilation and maintain a ruling class separate from the native population.

Spain: Conditional Tolerance and Ultimate Expulsion. Under Muslim rule in Al-Andalus, a degree of coexistence (convivencia) existed, though it was often precarious. As the Christian kingdoms reconquered the peninsula, they initially granted rights to the subjugated Muslim (Mudéjar) and Jewish populations. However, this tolerance was always conditional and temporary. It culminated in the final Reconquest in 1492, followed immediately by the Alhambra Decree, which ordered the expulsion of all Jews who refused conversion. The same fate befell the Muslims shortly after. The goal was a purely Catholic Spain, achieved through forced conversion or exile.

The Italian Maritime Republics: Pragmatic Trade, Not Integration. In cities like Venice and Genoa, merchants from across the Mediterranean—Greeks, Arabs, Jews, Armenians—lived and traded. They were tolerated for their economic utility and often lived in designated quarters (fondachi). However, this was a pragmatic, urban coexistence strictly tied to commerce. These groups had no territorial autonomy or political power, and their status was always precarious, subject to the whims of the ruling patriciate.

The Holy Roman Empire & Eastern Colonization: Urban Rights, Not Ethnic Autonomy. In the German-speaking lands, the eastward expansion (Ostsiedlung) saw German settlers invited into Slavic territories like Pomerania and Prussia. They received privileges based on “German law,” which offered personal freedom and urban self-governance. This is the closest parallel to the Hungarian model. However, it was primarily a municipal model, granting rights to towns and their citizens, not to entire ethnic nations with territorial autonomy. It often created a privileged German urban elite ruling over a rural Slavic population, leading to social stratification rather than a partnership of nations.

Poland-Lithuania: A Multi-Ethnic Commonwealth of the Nobility. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (established in 1569) became one of the most diverse states in Europe, with a large population of Poles, Lithuanians, Ruthenians, Germans, Armenians, and Jews. Its “Golden Liberty” granted extensive rights to the nobility (szlachta), regardless of ethnicity or language. However, this was a model of noble privilege. The peasantry, regardless of background, was enserfed. While religious tolerance was notable (Warsaw Confederation, 1573), the system was fundamentally an alliance of elites, not a state-led integration of entire communities with their own territories and laws, as seen in Hungary.

The Hungarian Thesis: Systematic, Charter-Based Integration

Against this diverse backdrop, the Hungarian approach stands out in sharp relief. It was neither the urban pragmatism of Italy, the noble-centric model of Poland, nor the assimilatory hierarchy of Byzantium.

To understand the Hungarian model, one can look to its very origins. The state’s foundational philosophy was eloquently expressed by its first king, St. Stephen I (c. 975–1038), in his Admonitions to his son, Prince Imre. This unique approach was not an administrative accident; it was rooted in a foundational philosophy of statecraft. He offered a piece of advice that would echo through the centuries:

“Unius linguae uniusque moris regnum imbecille et fragile est.”

(“A kingdom of one language and one custom is weak and fragile.”)

This was far more than a Christian king’s benign plea for tolerance. It was a profound statement of steppe political ideology, repurposed for a Christian kingdom. The Magyars, like other great steppe empires (the Huns, Avars, and later the Mongols), understood that their strength lay in their ability to incorporate and organize a vast diversity of peoples—each with their own warriors, skills, and knowledge—under a central authority.

A “kingdom of one tongue” was the model of a sedentary, isolated, and therefore vulnerable people. In contrast, a confederation of several ethnic groups or tribes was resilient, dynamic, and powerful. Stephen, a king now firmly anchored in Western Christendom, did not abandon this core tenet of his ancestors. He transformed it. He argued that welcoming foreigners—”guests,” as he called them —who brought diverse “languages and customs” was the source of a kingdom’s strength, wisdom, and valor.

This wisdom, penned in the 11th century, provided the ideological DNA for the “pragmatic pluralism” that would define the Kingdom of Hungary. The royal charters we will examine are the direct legal and political descendants of this foundational, hybrid idea: a Christian monarchy built on the steppe principle that true strength lies in a unified diversity, not in a weak and fragile uniformity.

From the 12th century onwards, particularly after the devastating Mongol invasion (1241-42), the Árpád and Angevin kings pursued a deliberate policy of “pragmatic pluralism.” The core instrument of this policy was the royal charter (privilegium).

Unlike the ad-hoc or purely urban privileges seen elsewhere, the Hungarian system was systematic & state-led: A repeated, crown-sponsored method for populating lands, boosting the economy, and securing frontiers. It was also territorial, as it often granted self-rule not just to a town, but to entire regions (e.g., the Szepesség for the Saxons, Kunság for the Cumans).

The Hungarian crown formally negotiated pacts with distinct groups, creating a mosaic of nations under the Holy Crown. This was a unique and enduring experiment in building a state not on uniformity, but on a framework of negotiated coexistence.

In the subsequent chapters of this series, we will delve into the specifics of these remarkable agreements. You will read more about:

- Steppe Warriors in a Christian Realm: The Cumans and Jász of the Great Plain

- The German Guests: From the Zipser Saxons to the Transylvanian Settlers

- The Original Frontier Guards: The Székelys of Transylvania

- The Kenéz and the Vlachs: Integrating a Pastoral People

- Slavic Partners: The Privilegium Slavorum and the Croatian Personal Union

- The Hajdú Soldiers: A Non-Ethnic Collective Nobility

- The Climax of Tolerance: Transylvania and the Dawn of Religious Freedom

- The Jews and the Roma in the Age of Privileges

- The Legacy – The Double-Edged Sword of Medieval Pluralism

This series seeks to dismantle the “prison of nations” narrative by revealing a far more complex truth: for centuries, the Kingdom of Hungary was a realm where diverse peoples could flourish under a unique system of rights. At a time when the distinct identities of the Celtic nations were being systematically eroded, the various ethnic groups within Hungary’s borders saw their communities grow, even attracting new members from Ottoman-occupied territories. The great irony is that the Hungarian populace, which had provided the framework for this coexistence, was itself brought to the verge of demographic collapse after centuries of war against two empires. The post-WWI dismemberment of Hungary cannot be understood without first appreciating the intricate and resilient mosaic of peoples that modern nationalism so tragically failed to comprehend.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn