Duke Béla (c.1245 – Margaret Island, November 1272) was the Duke of Macsó, son of Rostislav III, Grand Prince of Kiev, and Princess Anna of the Árpád dynasty, and grandson of Béla IV. His sister, Kunigunda, was the wife of Ottokar II, King of Bohemia, while his other sister, Margaret, spent her life in the convent on Margaret Island.

After his father’s death, from 1263 to 1272, he held the title of Duke of Macsó and Ban of Bosnia. During the civil war that raged between King Béla IV and the younger King István V from 1264 to 1265, he sided with Béla IV. He led the king’s troops in the Battle of Isaszeg in March 1265, in which István V was victorious. Prince Béla managed to escape.

After the death of Béla IV, he became a supporter of his uncle, István V, and participated in István’s war against Ottokar II, King of Bohemia, in 1271. In 1272, he was in his twenties when István V died. The heir to the throne, László IV, was only 10 years old, and his mother, Erzsébet the Cuman, managed affairs on his behalf. While preparations for the coronation were underway in Székesfehérvár, rebels captured the young heir, then also attacked the queen, but they were ultimately subdued, and László was freed. The rebels likely intended to make the already adult Béla king.

Among the rebels, Egyed of the Monoszló clan and his brother, Gergely, fled to the court of Ottokar, where other Hungarian barons who had supported Béla IV and had fled from István V were already staying, including the most prominent among them, Kőszegi I Henrik. Ottokar received Egyed warmly and endowed him with numerous estates. This so offended Henrik that he left Ottokar and came to the Hungarian court to offer his services, where he was warmly received.

Meanwhile, László’s coronation took place, and the court moved to Buda, where in the autumn they often held festivities on Margaret Island. On one such occasion, around mid-November, Kőszegi Henrik accused Duke Béla of treason, and during the ensuing altercation, he drew his sword. He hacked the prince to pieces so severely that afterwards, his sister Margaret and the other nuns gathered his remains and buried them in the convent.

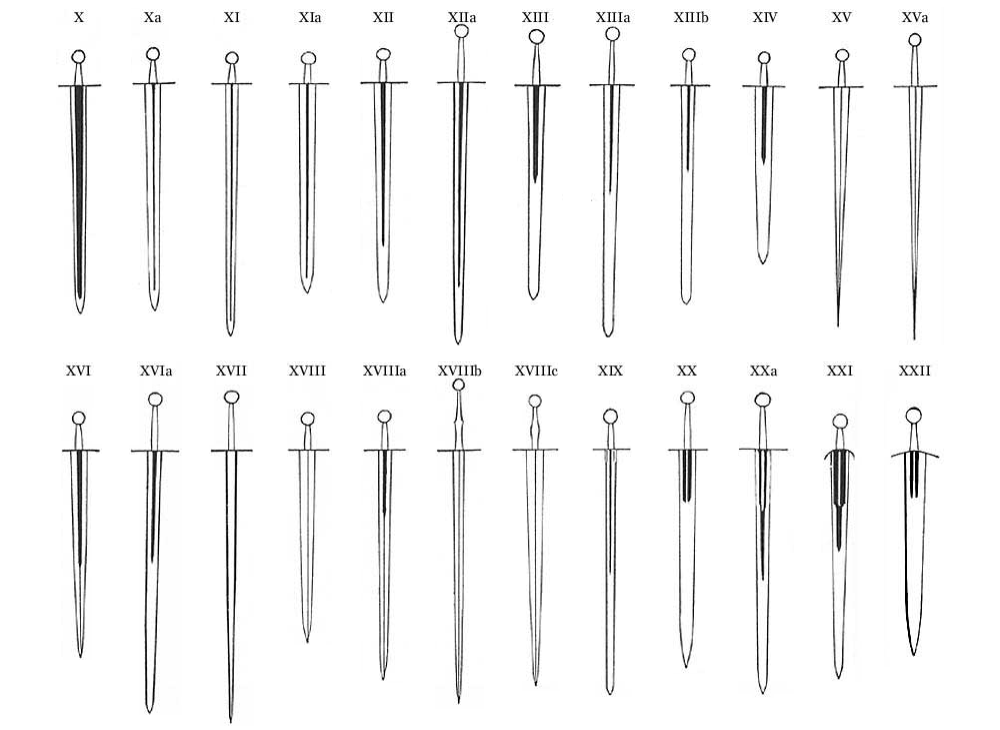

According to a study published in 2018, he was killed with a sabre and a longsword, and he was attacked from the front and the side; he heroically tried to defend himself but stood no chance against the overwhelming force. The intensity of the aggression indicates strong emotional involvement, according to the researchers. With respect to weaponry used in the region in the late 13th century AD, the first weapon could be identified as a Cuman-style saber, while the second type was a double-edged longsword of Oakeshotte´s Type XII or XIII.

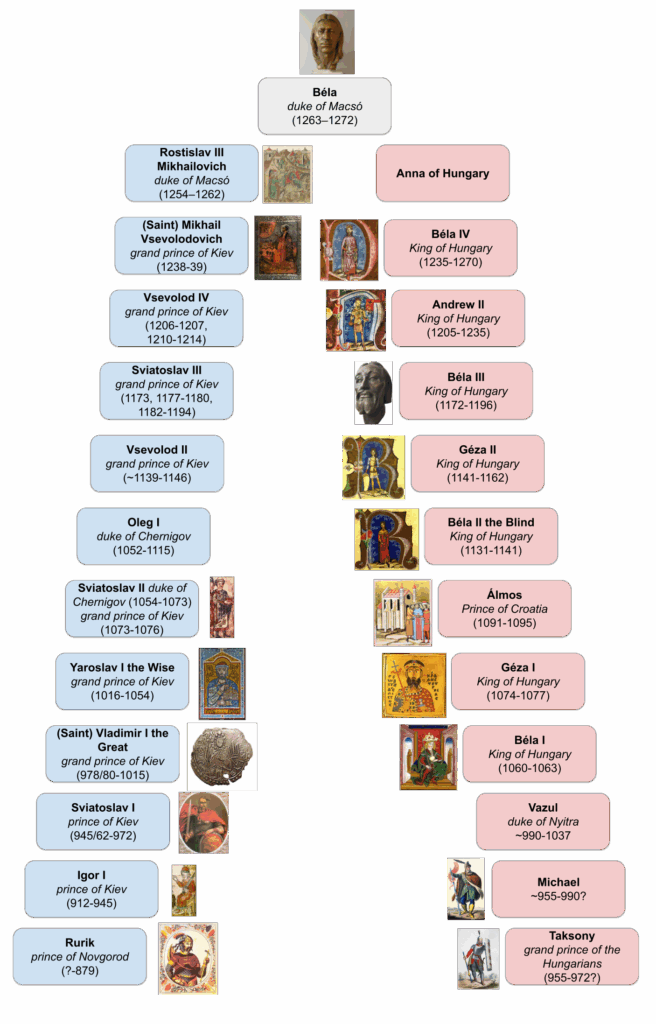

During the detailed examination of the bones, a DNA test was also conducted, on which an article was published in 2025. According to it, the individual was a great-grandson of King Béla III and, on the paternal line, a member of the Rurik dynasty, thus clearly proving that the bones belonged to Duke Béla.

His facial features were reconstructed by Gábor Emese, a portrait sculptor specializing in facial reconstruction, who is a staff member of the László Gyula Research Centre and Archive at the Institute of Hungarian Research. The artist used the latest 3D printing technology based on CT scans to replicate the original skull.

Murder in cold blood? The forensic and bioarchaeological identification of Árpád dynasty Duke Béla of Macsó

Article by ELTE Research Centre for the Humanities

An international project led by Hungarian researchers has successfully identified the remains of Béla, Duke of Macsó, a former member of the Árpád and Rurik dynasties. The research, coordinated by Hajdu Tamás (Department of Anthropology, ELTE Faculty of Science), involved Szécsényi-Nagy Anna and Borbély Noémi from the ELTE Institute of Archaeogenomics, who were responsible for genetic analyses. The investigations have solved a century-old archaeological and historical question. The results well illustrate how effectively historical data can be verified and past violent deaths reconstructed in unprecedented detail through the collaboration of the humanities and natural sciences. The new study has been published in the prestigious forensic genetics journal Forensic Science International: Genetics.

In 1915, during an archaeological excavation on Margaret Island in Budapest, the remains of a young man were uncovered in the sacristy of the Dominican monastery. Based on the burial context, historical data, the location of the interment, and the traces of injuries visible on the bones, it was hypothesized that the remains belonged to a prince of the Árpád dynasty, Béla, Duke of Macsó.

Duke Béla of Macsó (born after 1243 – died: Margaret Island, November 1272) had King Béla IV as his maternal grandfather. On his father’s side, he belonged to the Rurik dynasty, which was of Northern, Scandinavian origin and provided numerous Grand Princes of Kiev from the 9th century onwards, spanning seven centuries. According to 13th-century Austrian chronicles, Ban Kőszegi Henrik of the Héder clan and his accomplices carried out an assassination attempt against Duke Béla of Macsó in November 1272. Based on contemporary sources, Béla’s severely mutilated body was gathered up by Margit (Béla’s sister) and Erzsébet (Béla’s niece), and he was buried in the Dominican monastery on the island.

Following the excavation, the anthropological finds were sent to Bartucz Lajos at the Institute of Anthropology of the University of Budapest (now the Department of Anthropology at ELTE Faculty of Science) for analysis. Bartucz wrote about the bones in a newspaper article as early as 1936, and then published a photograph of the skull in his 1938 book titled “Magyar Ember” (The Hungarian Man). After this, no further reports were made about the bones until 2018.

Representatives of the anthropology profession believed that the remains had been lost during World War II. However, by chance, it was discovered in 2018 that the postcranial bones had ended up in the anthropological collection of tens of thousands of items in the Anthropological Repository of the Hungarian Natural History Museum, stored in a wooden crate, while the skull was found in the Török Aurél Collection of the Department of Anthropology at ELTE.

In 2018, an international research group was formed under the leadership of Hajdu Tamás (Department of Anthropology, ELTE Faculty of Science). The group included specialists in anthropology, genetics, archaeology, and archaeobotany, as well as stable isotope and radiocarbon dating experts, and dentists. The primary goal of the project, achieved through a complex forensic and bioarchaeological analysis of the bone finds, was the genetic identification of the remains and the most complete possible reconstruction of the duke’s life and death.

This skeletal find is significant because, besides the remains of Béla III, Duke Béla of Macsó is currently the only verified descendant of the Árpád dynasty for whom almost the entire skeleton has been preserved. Furthermore, its study can provide data not only on the genetic background of the Árpád dynasty but also on that of the Rurik dynasty. The international collaboration included researchers from the University of Vienna, the University of Bologna, the University of Helsinki, and Harvard University. Among domestic institutions, participants included the Department of Anthropology at ELTE Faculty of Science, the Institute of Archaeogenomics at ELTE Research Centre for the Humanities, the HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research, and the Faculty of Dentistry of the University of Debrecen.

Anthropological analyses conducted anew within the framework of the project revealed that a young man in his early twenties, buried in the sacristy of the Dominican monastery on Margaret Island. The bone samples were dated in multiple radiocarbon laboratories, as the initial 14C isotope results indicated an age earlier than the expected second half of the 13th century.

However, through a series of investigations carried out by researchers from the Institute for Nuclear Research, it was possible to demonstrate that this phenomenon can be attributed to dietary reasons. The individual in question consumed large quantities of animal protein, including significant amounts of aquatic animals (fish and perhaps shellfish) that also fed on ancient carbon sources, which exerted a so-called “reservoir effect” on the bones.

The dental calculus of the individual under investigation was analyzed to further reconstruct their diet. More than a thousand microfossils were preserved in the dental calculus. The identified starch grains originated from wheat and barley, showing signs of grinding, cooking, and baking. The remains indicated the consumption of boiled wheat groats and baked wheat bread.

Based on the measurement results of strontium isotope ratios, which indicate past individual mobility, the examined man was not born and did not spend his early childhood in the same location where he was buried. The early childhood values correspond, among other regions of the Carpathian Basin, to those measured in Syrmia / Szerémség (now part of Croatia and Serbia), areas that were once part of the Banate of Macsó in the Kingdom of Hungary. In late childhood, the individual moved to another region (which could have been the area of present-day Budapest).

The conclusive genetic identification of the examined man was carried out by Szécsényi-Nagy Anna and Borbély Noémi at the ELTE Institute of Archaeogenomics. The genealogy indicated by historical sources can be supported by multiple, mutually reinforcing pieces of genetic evidence. The data clearly confirm that Duke Béla of Macsó was the great-great-grandson (a fourth-degree descendant) of King Béla III, and consistently, the prince’s genetic distance to Saint László (Ladislaus) is approximately twice as large.

The results of the genetic composition estimate, based on full genomic data, point largely (to nearly half) to a Scandinavian genetic component. Additionally, it contains significant East Mediterranean components and, to a lesser extent, an Early Medieval Central European component. The exceptionally high amount of Northern genetic component present in the examined man confirms the connection to the Rurik dynasty, while the Eastern Mediterranean connection points towards the maternal grandmother of the individual studied.

Duke Béla of Macsó’s maternal grandmother was Maria Laskarina, the daughter of a Byzantine emperor and the wife of King Béla IV. Y-chromosome studies also confirmed the historical data concerning the examined individual’s paternal Rurikid lineage. In 2023, a Russian archaeogenomic study identified the same paternal lineage from the remains of a 13th-century Rurikid (Dmitry Alexandrovich); this dynastic family tree on the male line can be traced back to Yaroslav the Wise (Yaroslav Vladimirovich). Furthermore, the well-researched genetic data of living descendants of the Rurik dynasty also very strongly support Duke Béla’s paternal Rurikid connection.

In order to ascertain the precise circumstances of the duke’s death and to compare them with known historical accounts, a detailed forensic anthropological analysis was also conducted as part of the investigation series. During the forensic anthropological and dental examination of the skeleton, 26 injuries related to his death were observed—nine on the skull and 17 on the postcranial skeleton—all of which were inflicted during a single violent event. The injuries likely indicated a coordinated attack by three individuals. One perpetrator approached the victim from the front, while the other two attacked the victim simultaneously from the left and right sides.

Based on the location of his injuries, the prince faced his assassins in an open confrontation, was aware of the aggression, and attempted to defend himself. The attackers used two different types of weapons for the murder: a likely saber and a longsword. Based on the clean and deep cut marks, the victim was not wearing armor at the time of the assassination. A new reconstruction of the attack sequence suggests that the assault began with sword blows to the head and upper body. Then, as the victim tried to block further strikes and slashes, he sustained defensive wounds.

The attackers ultimately incapacitated the victim with further blows delivered from the side. They continued the assault, and when the prince fell to the ground, the assassins inflicted fatal injuries to his head and face. The intensity of the aggression, along with the numerous cuts and blows to the face, suggested intense emotional involvement (such as sudden rage or hatred), while the coordinated nature of the injuries’ placement makes a premeditated murder likely. Based on the above, although the assassination attempt carried out against Duke Béla of Macsó in November 1272 was partly or fully premeditated, it was by no means carried out in cold blood.

Researchers and institutions involved in the study:

- Tamás Hajdu, Project Leader, First Author of the study: ELTE Faculty of Science, Department of Anthropology, Budapest, Hungary; and Centre for Applied Bioanthropology, Institute for Anthropological Research, Zagreb, Croatia

- Noémi Borbély, Corresponding Author: ELTE Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute of Archaeogenomics, Budapest, Hungary; and ELTE Faculty of Science, Doctoral School of Biology, Budapest, Hungary

- Zsolt Bernert and Ágota Buzár: Hungarian Natural History Museum, Budapest, Hungary

- Tamás Szeniczey: ELTE Faculty of Science, Department of Anthropology, Budapest, Hungary

- István Major, Mihály Molnár, Anikó Horváth, László Palcsu, Zsuzsa Lisztes-Szabó: Isotope Climatology and Environmental Research Centre (ICER), HUN-REN Institute for Nuclear Research (ATOMKI), Debrecen, Hungary

- Zsuzsa Lisztes-Szabó: University of Debrecen, Faculty of Science and Technology, Department of Botany, Debrecen, Hungary

- Claudio Cavazzuti: Department of History and Culture, Alma Mater Studiorum, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- Barnabás Árpád Kelentey and János Angyal: University of Debrecen, Faculty of Dentistry, Debrecen, Hungary

- Balázs Gusztáv Mende and Kristóf Jakab: ELTE Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute of Archaeogenomics, Budapest, Hungary

- Ágoston Takács: Budapest History Museum, Castle Museum, Medieval Department, Budapest, Hungary

- Olivia Cheronet and Ron Pinhasi: Department of Evolutionary Anthropology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

- David Emil Reich: Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, USA; Department of Human Evolutionary Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, USA; Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, USA; and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Boston, USA

- Martin Trautmann, Corresponding Author: Department of Cultures/Archaeology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; and A und O – Anthropologie und Osteoarchäologie Praxis für Bioarchäologie, Munich, Germany

- Anna Szécsényi-Nagy, Last Author of the study: ELTE Research Centre for the Humanities, Institute of Archaeogenomics, Budapest, Hungary

Sources: https://www.fsigenetics.com/article/S1872-4973(25)00161-9/abstract and https://www.abtk.hu/hirek/gyilkossag-hidegverrel-az-arpad-hazi-macsoi-bela-herceg-igazsagugyi-es-bioregeszeti-azonositasa

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn