Today, 540 years ago, on 6 February 1486, King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary confirmed and extended the privileges of the Transylvanian Saxons. This act finalized the creation of one of the medieval world’s most remarkable systems of ethnic self-government. As we continue our series exploring the Kingdom of Hungary’s unique charter-based integration of distinct groups, we turn from the Jász and Kun to the Germans, whose structured settlements and formidable “German law” shaped the realm’s economy, landscape, and legal culture for centuries.

The Foundation: “German Law” and the Royal Invitation

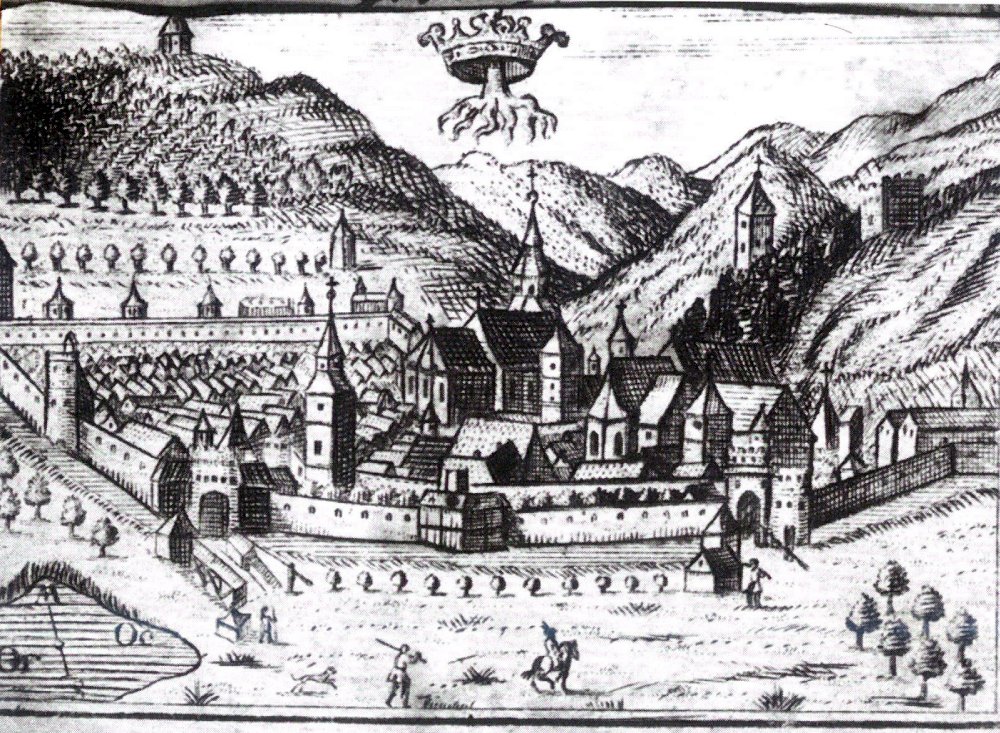

The initial phase of German settlement began in the mid-12th century, with colonists traveling to the region around Szeben (Hermannstadt, Sibiu). These Germans were sought for their mining expertise and ability to develop the region’s economy. Most colonists in this area came from Luxembourg and the Moselle River region.

The second phase of German settlement during the early 13th century consisted of settlers primarily from the Rhineland, the Southern Low Countries, and the Moselle region, with others from Thuringia, Bavaria, and even from other lands of France. Continued immigration from the Empire expanded the initial colonist area of the Saxons further to the east. Settlers from the Hermannstadt region spread rapidly into neighboring lands. The term “Saxon” was applied to all Germans of the region because the first German settlers who came to the Hungarian kingdom were poor miners or convicts from Saxony.

In 1211, King András II of Hungary invited the Teutonic Knights to settle and defend the southeastern corner of Transylvania, to guard the mountain passes of the Carpathians against the nomadic Cumans. The Knights constructed numerous castles and towns, including the major city of Brassó (Kronstadt, Brasov). Alarmed by the Knights’ rapidly expanding power, in 1225 King András II expelled the Order, which henceforth relocated to Prussia in 1226, although their colonists remained in Transylvania.

The Kingdom of Hungary’s medieval eastern borders were therefore defended in the northeast by the Nösnerland Saxons, in the east by the Hungarian Border Guard tribe Székelys, in the southeast by the castles built by the Teutonic Knights and Burzenland Saxons, and in the south by the Altland Saxons.

Before diving into the famed charters, we must understand the foundation: the “hospes” (guest) status and “German law” (Ius Teutonicum). This was not a single law, but a comprehensive package of privileges granted to Germanic settlers who were invited by Hungarian kings. Its core tenets included:

- Personal Freedom: Settlers were free men, not serfs.

- Hereditary Property Rights: Land could be inherited and sold.

- Fixed and Favourable Tax Obligations: Taxes were collective and predictable.

- The Right to Self-Governance: The community could elect its own judge (comes) and administer its affairs according to its own customs.

This legal framework was a powerful tool for development, transforming wilderness and border regions into prosperous, loyal communities. It laid the groundwork for something even greater in Transylvania.

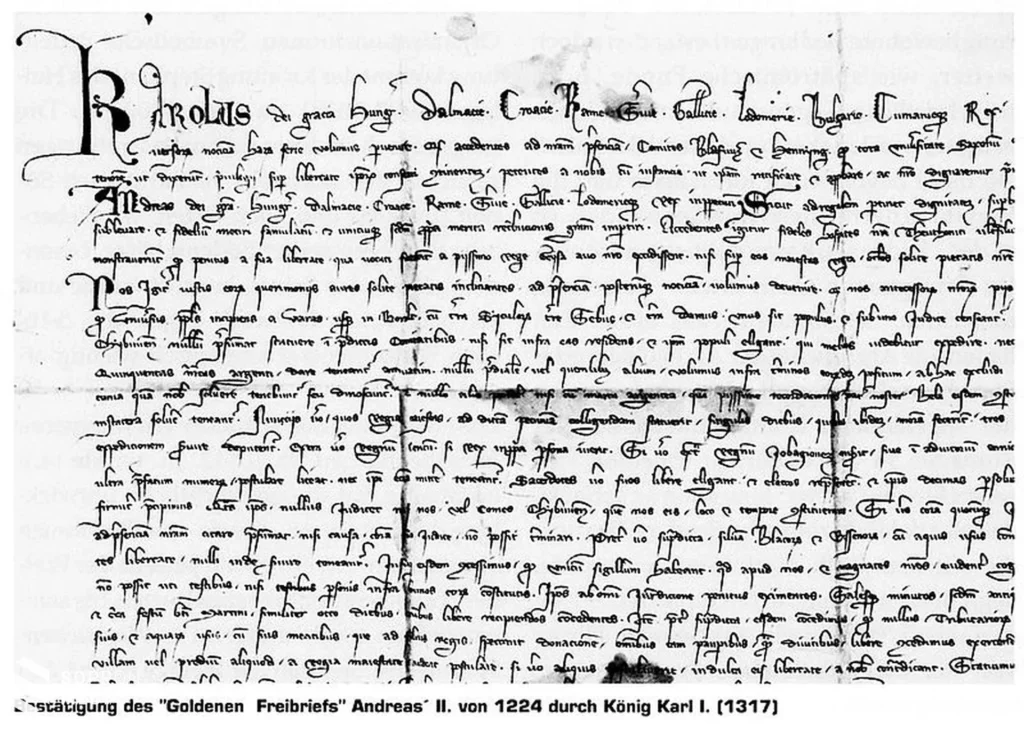

The Golden Charter: The Andreanum of 1224

The first monumental step was the Andreanum, issued by King András II in 1224. German historians rightly call it the ‘Goldener Freibrief’ (Golden Charter of Freedom). It arose from a practical need: the Saxons, settled in southern Transylvania, were under the rule of various lords, leading to conflicts and erosion of their rights.

The Andreanum unified the Saxon settlements—from Szászváros/ Broos / Orăștie to Barót / Baraolt / Baraolt and Daróc / Dorfbach / Dorolțu—into a single administrative entity directly subordinate to the king. It established the “Universitas Saxonum” – the Community of the Saxons. Key privileges included:

- Political Autonomy: The right to elect their own Count (Graf), who answered solely to the king.

- Military Self-Organization: The obligation and right to raise their own troops for the king’s service.

- Judicial Independence: Their own legal system and courts.

- Economic Control: Rights over trade, mines, and the disposition of their taxes.

This charter created a “state within a state,” a collective ethnic autonomy that made the Saxons a foundational pillar of Transylvania alongside the Hungarian nobles and the Székelys.

The Built Heritage

In the Middle Ages, about 300 villages were defended by Kirchenburgen, or fortified churches with massive walls, built not only in Saxon settlements. Though many of these fortified churches have fallen into ruin, nowadays the south-eastern Transylvanian region has one of the highest numbers of existing fortified churches from the 13th to 16th centuries, as more than 150 villages in the area count various types of fortified churches in good shape, seven of them being included in the UNESCO World Heritage.

One of them was the famous church of Szászveresmart (Roiderbrich, Rotbav), 24 kilometers from Brassó (Brasov, Kronstadt), whose ancient tower was built in 1250, and has recently collapsed in 2016, due to utter neglect.

The Birth of the Universitas: The Act of 1486

For over two centuries, the Andreanum’s provisions evolved. The Saxons were organized into the “Seven Seats” (Sieben Stühle) after 1324. They acted as a unified body in the Union of the Three Nations (1437-1438) with the Hungarian and Székely nobility. However, the decisive, formal birth of their consolidated self-government is marked by 6 February 1486.

On this day, King Matthias Corvinus, in Buda, handed a document to Thomas Altemberger, the mayor of Nagyszeben / Hermannstadt / Sibiu. This charter confirmed the Andreanum’s privileges for all Saxons in Transylvania (universorum Saxonum… Transsilvanorum) and extended them uniformly across the entire Királyföld / Königsboden / Fundus Regius (Royal Lands).

Thus, the Erdélyi Szász Univerzitás / Sächsische Nationsuniversität / Universitas Saxonum was born as a definitive political body. From 1486 to 1876, it was the central self-governing institution of the Transylvanian Saxons.

- Leader: It was led by the Saxon Count (Szász Gróf / Sachsengraf), elected by the Saxon nation and confirmed by the king, who was also the mayor of Nagyszeben.

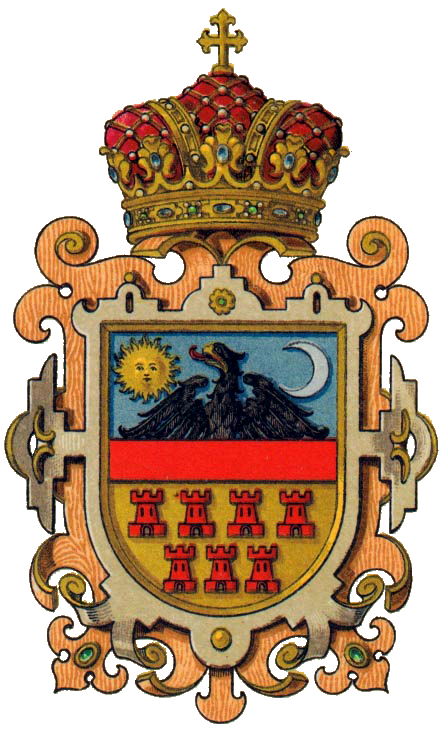

- Scope: Its authority extended over the Seven Seats (Szeben / Hermannstadt / Sibiu; Újegyház / Neugebäu / Nocrich; Szászsebes / Mühlbach / Sebeș; Nagysink / Grossschenk / Cincu; Segesvár / Schässburg / Sighișoara; Szászváros / Broos / Orăștie; Szerdahely / Reussmarkt / Miercurea Sibiului), plus the districts of Brassóvidék / Burzenland / Țara Bârsei and Besztercevidék / Nösnerland / Bistrița. You can see these seven towns in the Coat of Arms of Transylvania that represent the Saxon cities.

- Powers: It possessed legislative, judicial, economic, and political decision-making powers. It apportioned taxes, regulated prices and measures, granted guild charters, and was the sole judicial authority for Saxons. It was subordinate only to the king (and later, the Prince of Transylvania).

Trials, Resilience, and Dissolution

The Universitas was not without challenges. It fiercely defended its privileges against encroachments, such as from Prince Báthory Gábor in 1610, and successfully petitioned for their restoration from figures like Bethlen Gábor and Rákóczi II György.

The Habsburg era brought new tests. While the Diploma Leopoldinum (1691) confirmed Saxon rights, Emperor Joseph II dissolved the Universitas and confiscated its property in 1784. It was restored in 1790 following the repeal of his reforms.

The final act came with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise and the union of Transylvania with Hungary. Law XII of 1876 abolished the Universitas as a political and administrative body. Its properties were converted into a cultural-educational fund. This fund, the last vestige of the Saxon institution, was ultimately dissolved and its assets partitioned in 1937 by the Romanian state. It is quite likely that the abolishment was the reason why the Saxons supported the Romanian takeover after 1918, in the vain hope of receiving better treatment. They had to disappoint in it, though; there are almost no traces of them in present-day Romania.

They numbered 250,000 in 1910, and there were 15,000 in 2004. Presently, their average age is 69. Sadly, many times their empty houses are occupied by Roma people (Gypsies) who do not preserve their condition properly.

A Legacy of Ordered Liberty

The story of the Transylvanian Saxon Universitas is a profound chapter in our series on Hungarian constitutional traditions. For over 650 years—from the Andreanum to its final dissolution—it demonstrated how the Crown could forge enduring loyalty by guaranteeing collective freedoms. It created a stable, prosperous, and militarily capable community that was integral to Transylvania’s identity and defense.

Under the influence of Johannes Honterus, the great majority of the Transylvanian Saxons embraced the new creed of Luther. Almost all of them became Lutherans, with very few Calvinists, while other minor parts of the Transylvanian Saxons remained staunchly Catholics or were converted to Catholicism later on. In Transylvania, being a Saxon meant being a Lutheran, and the Lutheran Church was a Volkskirche, i.e., the „national church” of Transylvanian Saxons.

Politically speaking, the Saxons had always been loyal to the Hungarian king or to the Prince of Transylvania. Yet, it is natural that many times they supported the Habsburgs or those powers who offered more safety. Sometimes they were very unfortunate, according to a Saxon singer, Michel Behei,m who described how Voivode Vlad III of Wallachia had hundreds of Saxons impaled. Consequently, the Saxons did not have much love for the Wallachians in the 15th century.

You can read more about the Transylvanian Saxons on my page: https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/essays/who-were-the-german-saxons-in-transylvania/

The Zipser Saxons and Their Willkür

The Szepesség (Slovak: Spiš; Latin: Scepusium, Polish: Spisz, German: Zips) region was an administrative county of the Kingdom of Hungary, called Scepusium before the late 19th century. Its territory today lies in northeastern Slovakia, with a very small area in southeastern Poland.

The German settlers had been invited to the territory from the mid-12th century onwards, and they also enjoyed a charter-based autonomy that was not limited to Transylvania. Now, we will journey to the north to explore its counterpart: the Zipser Saxons of Upper Hungary, whose own network of privileged towns, like Lőcse / Leutschau / Levoča and Késmárk / Kesmark / Kežmarok, operated under a similar, though distinct, framework of “German law.” Their story further underscores the Kingdom of Hungary’s intricate and pragmatic approach to governing a mosaic of peoples.

As we turn our gaze north, to the rugged, mineral-rich landscapes of Szepesség / Zips / Spiš, we must remark on the outstanding scenery. No wonder that the word “Szepes” derived from the Hungarian word for “beautiful”, “szép”. Here, a different model of Germanic autonomy flourished—one not of a single “Saxon Land,” but of a formidable federation of free mining towns, bound by a common legal code: the Zipser Willkür.

In the 12th-13th centuries, Saxons settled in Upper Hungary. Their very first group arrived during the reign of King Béla III, in the 1180s; they were already present in Késmárk / Kesmark / Kežmarok by 1190.

Colonization After the Storm

The leader of the settled Saxons, Arnold, son of Arnold, held the position of lord lieutenant. During the Mongol invasion, his son named Jordan, led the population of the Szepesség / Zips / Spiš region to safety in the mountains. The Mongol invasion of 1241-42 left the Kingdom of Hungary decimated, with perhaps half its population lost. King Béla IV, in a desperate and visionary rebuilding effort, issued a sweeping invitation to Germanic settlers. They came not only to Transylvania but also to the northern counties, to Szepes.

These settlers were not primarily farmers. They were traders and, most importantly, miners, drawn by the rich deposits of copper, iron, and precious metals in the Carpathian slopes. Their expertise turned the region into an economic powerhouse, founding a chain of prosperous settlements that would evolve into mighty towns.

After the forces of King Károly I, who was fighting against the oligarchs, were pushed into the Szepes region in 1312 by the armies of Aba and Csák Máté, the Zipser Saxons sided with the king and fought on his side in the Battle of Rozgony / Rozhanovce. The king was grateful for their loyalty. The privileges that had been valid for the Saxons since the beginning of their settlement were confirmed by Károly I in 1317, according to which the county’s lord lieutenant exercised only nominal authority over their own laws and governing bodies.

By 1370, these communities had codified their common legal framework: the Zipser Willkür (Zipser Charter). This law guaranteed their self-governance, property rights, and unique customs, forming the bedrock of their privileged status.

The Province of 24 Towns: A Federation of the Free

At its height, this community coalesced into the Province of 24 Szepes Towns. This was not a territorial block like the Transylvanian Királyföld, but a federation of urban communities, each self-governing yet united for common defense, trade, and legal affairs. They stood as direct tenants of the Hungarian crown, largely independent of the local county nobility. The last wave of Germans arrived in the 15th century. In the mid-15th century, the marauding campaigns of the Bohemian mercenary leader, Jiskra, devastated the area.

Their autonomy, however, faced a unique and prolonged interruption due to high medieval finance. In 1412, King Zsigmond (Sigismund) of Luxembourg, needing vast sums to fund his anti-Ottoman wars, pawned 13 of these towns and the royal domain of Ólubló / Altlublau / Stará Ľubovňa to the Kingdom of Poland for 37,000 Prague groschen, that is, approximately 7 tonnes of pure silver.

What was meant as a short-term loan became a 360-year separation. These pledged towns (including Lőcse / Leutschau / Levoča and Késmárk / Kesmark / Kežmarok) lived under Polish sovereignty until 1772, while the remaining 11 stayed under Hungarian rule. Remarkably, throughout this time, the Zipser Willkür and their Germanic civic identity endured, a testament to the strength of their chartered liberties.

You can read more details of this event on my page: https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/history-after-1699/1772-the-16-towns-of-the-szepesseg-are-returned-to-the-hungarians/

Coexistence and a Tragic End

Life in the Zipser towns was not exclusively German. A distinct Hungarian frontier guard community, the “Sedes X lanceatorum” (County of the Ten Lancers), existed within the same region, highlighting the mosaic nature of these lands. They were also called “gömörőrök” (Guards of Gömör County). For centuries, despite the upheavals of the Ottoman Wars and anti-Habsburg uprisings, the Zipser German community remained a pillar of culture and industry.

From the mid-16th century, the majority of Saxons, under the influence of the German Reformation, adopted the Lutheran faith. In the 17th century, due to increasing economic burdens and the effects of the Counter-Reformation, the German population began to move away, and Slovaks settled in their place.

The Saxons’ remaining privileges were completely abolished by the decrees of Emperor Joseph II and the administrative reform of 1876. Yet, the Zipser Saxons never ceased supporting their fellow Hungarians: to help the Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–49, a Zipser regiment was established that fought against the Habsburgs.

The final blow, however, was not gradual but brutally abrupt. Following World War II, under the infamous Beneš Decrees, the centuries-old German community of Czechoslovakia—including the Zipser Saxons—was collectively declared guilty of collaboration. They were stripped of citizenship and property, and in 1945-46, nearly the entire population was forcibly expelled to a devastated post-war Germany. This act erased a living, 800-year-old chapter of Central European history in a matter of months.

Conclusion: Two Models, One Principle

The journeys of the Transylvanian and Zipser Saxons present two brilliant variations on a theme central to the historical Hungarian polity. In the south, a territorial autonomy (Universitas) was born from the Andreanum. In the north, an urban-confederate model (Willkür) united a league of towns.

Both, however, were rooted in the same powerful principle: the Crown’s grant of collective privilege and self-governance in exchange for economic development, military service, and political loyalty. This charter-based system allowed for a profound, structured coexistence, turning diverse “guest” communities into foundational pillars of the realm. Their stories are not mere footnotes but central narratives in understanding the complex, constitutional, and tragically fragile tapestry of Central Europe.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn