The Heavenly Advocate

By Kosztolányi Dezső (1920)

Translated into English by Szántai Gábor, and edited by Suzanna King (2021)

The translator’s foreword:

One would think that this short writing has nothing to do with the Ottoman-Hungarian wars. The following story written by Kosztolányi Dezső is rather an artistic description of the consequences of these wars. During the centuries of struggle against the Ottomans, Hungary has been mortally weakened, ethnically and politically alike. After the Ottoman wars, the Habsburgs took over control and dragged the country inevitably into the Great War in 1914.

The “Heavenly Advocate” is the first writing that Kosztolányi Dezső created after the fall of the Hungarian Soviet Republic (1919). Regarding the entire Hungarian literature during the last 100 years, I have never read a more shocking and better work about the partition of Hungary. The partition made in Trianon was worse than the one in 1541 when Buda fell to the Turks.

The Author approaches the tragedy in a very gentle and human way while not offending any other nations. It calls our attention to how simple people would react to traumatic experiences when the leaders of the country abandoned them.

In my translation, I used the Hungarian names according to the Oriental name order where family names come first. All the mistakes are mine, and all the thanks go to Suzanna King who edited the text. It is weird that this masterpiece has never been translated into English until 2020. As for the original Hungarian text, I added it for the sake of those of you who can read it.

May this work help us all to comprehend the incomprehensible.

Szántai Gábor, 2020 Budapest

The Heavenly Advocate

By Dezső Kosztolányi (1920)

Translated into English by Szántai Gábor, edited by Suzanna King (2021)

”Kaszás-Kis János ever since his youth had been a day laborer. From morning to night he pushed his wheelbarrow within the confines of his village.

This wheelbarrow whined like a sick child, plaintively, with much sadness.

János was always moving earth, a heavy greasy clay, among the farms. It was as if he wanted to upset the entire globe by transporting it from one place to another through endless, infinite, hopeless work.

He didn’t ask for more. His face bloomed, flushed with health. You couldn’t tell how old he was. Some aged him at forty-five, others twenty-five. He was as ageless as the earth.

He’d signed up for the war. Wounded twice, he suffered a nervous shock from the explosion of a grenade. For a long time, he trembled from that cold kiss with which death had touched his calm peasant head.

But as soon as he took off the uniform and was able to return to his village, his face blossomed, and his blue eyes resumed their gentle smile like the sky of the Hungarian Great Plain after a rainstorm.

János resumed pushing his wheelbarrow as before. He wore greenish-gray frayed military breeches and an ordinary wrinkled hat. He cordially smoked a pipe hanging from his tooth gap.

“Which countries have you seen?” – they asked him.

“The same what others have seen”- he replied.

His hardened, steely body did not show the slightest hint of fatigue. He never put on weight.

He had remained haggard as a result of constant physical labor for hundreds of years, through so many generations, he had failed to gain even an ounce. His thick chestnut hair formed a profuse crown around his head. But his mustache was not bushy, as if to show that the arid, marly ground of his flesh did not have enough vital force to grow such a stately ornament.

“But yet – they insisted – what did you do “there”, Uncle János? You were there since you even have the military medal.”

“We shoot each other” – he would answer and smile.

He didn’t like to talk much. His work finished, he returned to his cabin with his wife and two sons.

In the meantime, the village houses hoisted red flags made of bad paper fabric.

One August afternoon, as he busied himself with his work in the fields, he saw horsemen emerge from a cloud of dust wearing iron helmets and carrying long flagged pikes. From another side, they could already hear the shrill and deafening sound of trumpets that

scattered a mad fever into the lowland dust among the acacia trees.

“The Romanians” – they whispered.

Twenty to thirty men in all had just appeared, led by an officer, accompanied by two wagons loaded with crates and various other items.

Men, women, and children dressed in long white shirts, stood staring gap mouthed in front of the town hall and watched the Gypsi-like brown-faced soldiers disperse in the village. A few soldiers with fixed bayonets proceeded to clear the square.

At the edge of the square, János was sitting on his wheelbarrow smoking his pipe, From there he gazed with quiet wisdom at the dispersing people.

Suddenly he noticed that two soldiers with bayonets were approaching him. One of them shouted something at him in Romanian, but he didn’t understand. With that, they both began to wave their arms in fury. Seeing this, János got up slowly and respectfully while reaching for the handles of his wheelbarrow to go peacefully on his way.

Then, in the next second one of the Romanian soldiers struck him fully hard in the face.

His hat fell in the dust in front of him.

Panic broke out. The people of the village fled every which way at full speed. The women were crying.

“They have hit Kaszás-Kis János” – they exclaimed.

“Ah…”- exclaimed an old peasant wagging his head – “and he had been a soldier and all. . . even been in the war”

“For four years”- added another. – “The poor thing!”

In less than a minute, János was surrounded by five soldiers who took him to the town hall.

He waited in the courtyard, in silence, under the guard of the soldiers. Towards evening he was taken to the officer.

The latter, a very young manicured First Lieutenant, with a well-groomed exterior, who despite the scorching heat of the afternoon, did not take off his thick white gloves, was seated at a small table, legs crossed, smoking a cigarette. He proceeded to interrogate him with the help of an interpreter.

“Were any weapons found on him?” – he asked.

“Nah, I got nothing on me, please” – and as János was going to stick his hands in his pockets to show the contents.

They suddenly grabbed him.

– “Search him!” – ordered the officer to his soldiers.

A pipe, a filthy red peasant handkerchief, a crumpled twenty-five Soviet crown note, were found in his pockets.

“Doesn’t he have any guns on him, either?”

“No”.

The officer sent two iron-helmeted soldiers to János’ house to carry out a search, then, turning to the interpreter, he delivered his orders jabbering:

“Tell him if he’s hiding guns, we’ll shoot him in the head right away. He will also have to deliver the cartridges. If he knows people with guns, revolvers, swords, denounce them, give them up, or else… Scare him, threaten him.”

Outside, the village was already buried in the summer night. Soldiers roamed the streets. No one knew what would happen.

Returning, the men of the patrol announced that they had not found any weapons at János’ home. With that, the officer said a word to the interpreter, and János was released.

Shoving his hat on his head, dizzy, head bowed in humiliation, with staggering steps he fumbled his way home in the dark street. He wasn’t a drunkard. But this time, this time he felt like he was for he was groggy and his legs were tottering. Everyone was asleep already. Black windows stared at him. Only the August stars sparkled with an electric glow.

Pale, he stopped at his doorstep. His wife hugged him crying.

“So you came back?”

“Yep”

János sat down at the table. His wife brought dinner and laid it out in front of him.

“Eat”

But he could not eat. He pushed the dish away and let his head fall on the table.

“You can’t even eat anymore,” said the woman.

“It’s a public disgrace” János replied.

He opened his shirt and pointed at his chest.

On that hairy peasant chest was the pink trace of a scar.

”This here where the bullet came in,” he said pointing to it.

He fell back on the table again and his powerful chest shook with a dry tearless sob. He could not manage to cry. Only his teeth gritted and a sort of bark sprang from his throat.

”Don’t take it to heart that much”- the woman said to console him. “ Be glad they didn’t take you captive.”

“Skum!” – János growled.

“ Turn off the lamp… – she pleaded with him while undressing. – “They might see the light and will come in.”

They listened in the dark: patrols circulated in the quiet night.

For a long time, János could not fall asleep. He wanted to howl with the pain. He tossed and turned in his bed, pressing the pillow to his cheek. He had never been hit in his entire life, not even among the soldiers. In quarrels, his opponent always came off badly.

One day, in an argument with a lad, before it came to blows, he had stared at him in such a manner that the other one sheepishly walked away. He had terrible eyes.

Deeply humiliated, he covered his face with his two peeling palms, rough from earthwork.

Oh, how good it was that night now fell on him, dark, heavy, blanketing night.

It cooled his shame like a cold compress. He glanced around and was happy to see that the table, the chair, everything was dark around him. Only occasionally could he hear a bullet whistling in the distance.

In the morning he went to the well. He washed himself in the bucket for a long time even dipping his head into water.

“He has hit my left cheek” – he said to his woman – “here” – and he showed the trace of the affront like a sore.

“Can’t see naught”

“Nah, really”?

“Nah”, – the woman confirmed, examining her husband’s left cheek, bending over him, eyebrows twitched. “ You just go quietly about your business.”

Again the wheelbarrow began to creak, to cry. The village knew that everything was back to normal.

A glaring sun darted sharp brain-splitting rays on the earth. It was one of those mornings when the grassland already had a fever at dawn. As far as the eye could see was but dust and dullness, only here and there a poppy uttered its blood-red cry. Barefooted peasants hastened to lift their heels from the burning clods as if they were dancing on hot coals. From the distance came hoarse noises: the jolting of a peasant’s cart, the chain of a bucket that had difficulty reaching the bottom of a thirsty well. It was as if the sand itself was in a delirium; the noises themselves were delusional. Nowhere in the yellow infinity is there a spot of shade.

By midday the Komondor dogs were panting, wallowing on the ground, nibbling furiously at the hedge, or slinking, crazed, with bloodshot eyes, dragging their shaggy tails in the dust. The light made them sick too.

But, János trudged along indifferently. The brim of his hat was pulled down over his eyes, he stared vacantly at the earth.

“Good day!” a man greeted him.

Instantly he looked away blushing, hiding his disgrace.

“Cause it was not right” he explained to his woman. “ Whether he is Romanian and me Hungarian, that is no reason to hit me. He was armed, I was just bare-handed. But I looked him in the eye. I told him, I don’t mind, he could lead me afore his prince if he wanted; let him do justice…”

“What for you torture yourself. What happened, happened.”

Kaszás-Kis János did not want to appear in front of the men. It got around that he was angry with everyone.

“He has become so proud” the people of the village would say, offended.

“Sure enough, he is so proud of you-know-what.” – and they laughed heartily.

“Why you are always brooding?” – his woman asked him one evening.

“I was just thinking”.

They were both silent for a long time.

János broke the silence.

“Say, mother, how many Hungarians can there be in the world? They say there are twelve million.”

“But that is none of your business.”

“Romanians, there ain’t that many” – said János.

“Could be”

“ But the French, there are many, many. There may be twenty millions.”

He sank back into his thoughts again.

“And the English, too”, – he added, “There are lots of them, too. There are more of them than of the others.”

“Have you seen an Englishman?”

“ Nah, I have never seen one. I only saw Italians. At the front. There were masses of them, like hell. All these great mountains were full of them. My God, if one day …”

“Why do you mind other people’s affairs? The gentlemen will take care of it.”

Indeed, he ended up abandoning these thoughts. But, he kept thinking about what he needed to do to repair the affront, the shame that devoured him, no matter what others had said. Since that day he had come across the soldier several times. The latter walked indifferently in front of the town hall with his long bayonet fixed on the barrel, or he was seated on the ground, his white teeth chewing on a green apple. He looked at János without comprehension and with that extraordinary calm of the shepherds of the mountains. Maybe he didn’t even know who this Hungarian wheelbarrower was. János could see himself rushing at him, hitting him. . . twice, the same way. . . left cheek, right cheek. . . grab hold of his long, woolly black hair, pulling, tearing . . . yelling . . . screaming . . . or maybe stick a knife down his throat. . . red blood would spurt out. . .high like a fountain… Then – what did it matter to him? The other could stab him in the chest with his bayonet or even hang him from the mulberry tree that stood beside him.

At the beautiful thought of revenge, he almost fainted with joy. He felt dizzy and leaned against a tree so as not to fall.

But would that have made his public shaming disappear?

He shrugged and spat in the dust.

It wasn’t worth it.

However, he quite loved being alone, away from the men he hated. As much as he could, he avoided them so as not to be questioned about what he called his shame. He found he felt most comfortable in the stubble fields and on the lanes where privet and purple thistle flourished aimlessly and without reason.

The sweat poured from his forehead and he let himself fall, weary, in the shade of a haystack. Sometimes he thought of leaving the country, going to America or even further, far far away, to the end of the world, beyond the fabled Óperenciás sea, where there is nothing and where one can sit at the end of nothingness, legs dangling. It would be magnificent indeed. Only it took money, and the Romanians wouldn’t let anyone leave.

“Oh woe is me.” – he said, heaving deep sighs while his wheelbarrow creaked to the rhythm of the road.

And he added to himself: “ Alas misfortune has befallen us.”

One day Péter, the one-eyed mutilated man, was pushing his wheelbarrow next to his.

They walked side by side.

Suddenly János looked up exclaiming happily, “ Woe, woe, alas, alas, the trouble is upon us” – and he laughed almost with satisfaction.

Péter looked curiously at him. After a moment he asked:

“What do you say, János?”

“Not much. It was just as you heard.”

“Say it.”

“What, I said” “Woe, woe, alas, alas the trouble is upon us.”

“Hey, what trouble?”

“Misfortune, trouble, like what in tales.”

Péter twisted his mouth so his chipped teeth and bloodless gums were seen. With him, that grimace meant laughter.

“Sounds good to the ear” – he said, repeating, “alas on us, alas, on us…”

“For that, yes” – said János, “it sounds good.”

“ Do you know others like that?”

János scratched his head.

“Of course I know.”

“Where did you learn it?”

“Did not learn it anywhere. Just came to me.”

“It is funny” – said Péter – “like in a book.”

He grimaced again, nodding his tremorous head because he too had had the “cold kiss of death” on the battlefield.

This, too, was soon spread. The peasants surrounded János.

“Hey, how that goes, man?”

Militarily, János rose to attention and recited the rhyme aloud without embarrassment.

The peasants smiled.

“This one is funny” – said a woman – “he speaks in verse.”

“Tell more, Uncle János!”, he was prodded.

János raised his eyebrows,

“Rose red, peony white. Oh, how nasty, how revolting the whole world is.”

Bursts of laughter erupted.

“Yes, but it does not come out right,” remarked a peasant when silence was reestablished.

“Yes, it doesn’t”- János conceded, frowning his narrow forehead.

His face expressed excruciating pain, like the tightness of a migraine.

Then, forcing himself:

“Hay, straw, garland, wreath, you are crazy if you are sad. . . ”

These verses had extraordinary success. The others clapped and yelled with him:

“Hay, straw, garland, wreath, you are crazy if you are sad. . . ”

“He is right” – they said, nodding their heads in agreement “what is the point of grieving over it”

“Fortunately he forgot” – added the steward.

Indeed, János calmed down, his passions softened. From time to time he struck up a conversation with the peasants. He entered the pub, told tales of what he had done at the Italian front. The others liked him because he always knew how to tell them something heartbreaking, entertaining, unbelievable, here a poem, there a riddle. Then, after they had raised their elbows and the poison of the brandy had set their eyes a sinister glow, they begged him to sing. He had a shockingly bad voice; screeching, out of tune, like a broken pot. With that, no ear. But he knew how to joke and that was sheer pleasure to hear. He would put his hat over his ear, crumple his face to make others laugh, squint, and begin to belt out:

“On the wet edge of the parched lake

A dead frog starts to croak,

The deaf man splashing in the water

hears the frog go croak-croak-croak

Hay ho little bat, three times squeaks the mousy”

Fat roars of laughter swelled from the peasants’ mouths, like giant balls of dough. They were rolling with laughter.

“Again!” – they screamed.

Hoarsely, János cried to them:

“I have a dry throat.”

“You just have to wet it” – said a rich peasant, pointing to the brandy bottle and adding with pride:

“It’s me who pays”.

In a gulp, János emptied the bottle.

“Na-ya-don’t!”- screamed János, this was his favorite word when he wanted to infuriate himself “Na-ya-don’t!” and he swept the pub table with his staff. The glasses clinked and fell to the floor. He climbed up onto the table and bellowed at the top of his lungs.

After such revelry he would drag himself home at dawn, dead drunk.

One night the woman waited in vain for him. The daylight came without János having returned. Finally, he appeared at noon. Instead of being drunk, he was just gloomy and self-important.

“Where the hell did you hang out all night?”

He gave no answer. After looking around suspiciously, he closed the kitchen door on them.

It was only then that he confided to his woman, secretively, in a voice low as a breath:

“I was invited.”

“Invited, where the hell? ” said the woman wincing. “To the pub, no doubt, to cavorting about all night?”

“Nah, woman,” replied János “I was promoted to a great honor, to a high rank.”

And with both hands, he began to knead his forehead.

“It was done like that”, he continued -” I was sitting in the stubble. The evening was so silent and nice… I was smoking my pipe and I looked up at the stars… They were falling… tumbling down… thick, like the rain… Suddenly, who do I see? The sky, it opens up on three sides, it is bright as daylight and up there in the clouds… I hear music, loud as if twenty bands were playing at once. Then someone calls me by my name, “Kaszás-Kis János”. “Present,” I say, like in the army.” “You will have to settle the case of the Hungarians, as a Heavenly Advocate,” the voice tells me.”

“Very good, Sir, which says I, and bowed down to the ground.”

The woman listened to him speechless, mouth agape.

“What are you saying?”

“Sure enough. Even Saint David himself was a-playing his violin on the moon. Once it was proclaimed by law that Kaszás-Kis János must henceforth himself try to defend the interests of the poor people.”

The woman put down the knife with which she was peeling potatoes and let her children enter the kitchen. She shrugged her shoulders and spoke to her husband in her usual sour voice, “You better think of something else. . . Look at the kids. How skinny this little one is. You should rather provide for him. . .”- and with the corner of her apron, she wiped a tear from her face.

János looked at his little child. “Little kiddie, big kiddie, You are crazy if you’re dreary. “

“For that, you are clever”, she said roughly turning red in the face: “spouting nonsense and turning the words back and forth. You have to be crazy to come up with such stupidity. . .”

Her reproaches had some effect on him. So again, János diligently went to work during the day to the domain of the lord of the village where he was also given lunch and dinner. By the fall, his old military pants were tattered and torn. From the steward, he then obtained a pair of worn black trousers, cut in the Hungarian style which also looked like gentry wear. He also got a jacket that came down to his knees. In short, he was tiptop costumed. This masquerade had such a funny effect on his peasant’s body that it made anyone who saw him for the first time laugh. He looked like the scarecrow that chases gluttonous birds off the cherry trees.

János didn’t care much about it. He was constantly scrutinizing newspapers. The reading was not easy at first, but he got used to it eventually. At home, he set to work. On his soldier’s kit-box, he spread sheets of paper, sharpened with the household knife his carpenter’s pencil which for years had been forgotten in the drawer, and with childish characters, he laid down on the paper what had been racing around in his head. Most of them were verses and drawings. On a large sheet, he drew the Celestial Revelation, the Sun and the Moon, coloring them with a yellow pencil, then drew a red line symbolizing the Hungarians, a blue symbolizing the Romanians and a green indicating the Czechs and the Serbs, and, above the whole, a huge red-white-green flag dwelt.

Towards the middle of winter, the Romanians prepared for departure.

When the occupation ended they left the village and this event released János’ tongue:

“Well, what’ll be now?”, he was being asked, because they knew he was not a man of letters, yet he was declaiming like a deputy of Parliament.

Kaszás-Kis János was talking about Attila, Saint István, King Matthias Corvinus, and he knew everything worth knowing about Wilson and Clemenceau as well.

“There will be a meeting where all Hungarians will gather. But all of them who live on this land. By mutual agreement, they will create the League of Peoples, that is to say, the great law. There will also be a popular vote. Democracy there will be, too. Then we will learn the truth of the Hungarians, that is to say, that they were not guilty in the making of the war. And then will come the real war, the one that has never been, yet. Everyone will take part in it. Even the Hungarian kids will go and watch things, but they will only stay behind. They will be the ones who will collect the bullets that the enemy fires and the cartridges that will fall to the ground because in this war nothing must go to waste.”

“How do you know, Uncle János?”

“ It was announced to me, so to say, as a Heavenly Advocate, officially.”

The others nodded.

It was pointed out to him that henceforth he could demand reparation for the affront the Romanian soldier had inflicted upon him by beating him. But he pretended not to hear. Or perhaps he failed to comprehend it. It happened so long ago. It was beyond the Great Sea in that void that could console him.

In February, his wife appeared at the town hall, weeping. Her husband was gone, with his soldier’s kit-box, along with the few crowns they saved. In the village, it was said that he had lost his mind. Even the news of his death was spread.

As it was, one morning, without telling anyone, he walked to the train station. He had attached a bunch of Stipa feathergrass plumes to his round hat and clutched a short-shafted shepherd’s ax in his hand. Climbing into a third-class carriage, he had amused his traveling companions all the way from his village to Budapest. He gave them harangues, rhyming sayings, and they roared loudly, heaving with laughter.

A week later he emerged in Budapest. He was seen near the railway stations offering his poems drawn on green and red straw paper. But ‘Heavenly Appearance’ and ‘My Homeland’ did not find many buyers. Only refugees bought them who, though poor, bought everything where they hoped to find some good news.

János’ cheekbones were still ruddy, his eyes a limpid blue, his accent was tasty, that of the peasants, his speaking a model of his race, wise and moderate to the point of observing a lordly measure even in suffering, of having care of his dignity even in madness.

On his jacket, left side, above the heart, he had sewn a tricolor ribbon in the shape of a cross.

When asked why he replied:

“This because our Lord Jesus Christ was also crucified.”

In the mornings, he toured the city. From his shoulder hung a patched, well-worn peasant satchel in which he carried bread, sheets of paper, and the Drawing- representing the Moon, the Sun, and the Flag. Announce it everywhere. That is what he wanted in the offices of the ministries, in the editorial offices of the newspapers “so that they should acknowledge it officially” and “so that a decision is to be made on the innocence of all Hungarians”.

“Having practiced in the administration of justice, as a true and canonized Heavenly Advocate, I proclaim and I resolve the law of peoples” – he declared.

But, as he unfolded his writings and continued to speak, throughout his tasty peasant words pierced a strange, nightmarish flame, a wisp that astonished the listeners. They threw him a few crowns. Then, one day, he was not given anything at all. The ushers and the doormen dismissed this Hungarian peasant by the arm and slammed the doors on his heels.

So he started wandering around the city. Like a stray kuvasz, a peasant dog without an owner, its hair bristling and untidy, on the verge of becoming rabid, running about homelessly, and unable to find a place anywhere, he pounded the pavement of the foreign city. Having lost his hat somewhere, he walked around bareheaded.

He slept in the street or on benches. During a nightly roundup, police officers picked him up. Unable to show any papers, he was imprisoned for two days. They wanted to send him back to his village. Then, János was given accommodation in a railway wagon on the pretext that he was a refugee. This was where he now wrote all kinds of funny and sad lines that he recited aloud as he walked the streets.

After a few months, his clothes were hanging in rags on his body. Grime covered his collar. One day, at a pub in Kispest, he was beaten and kicked out of the door. For a long time, two bloody streaks marked his face. Passers-by stopped in front of the versemonger and looked at him, as he somewhat resembled Hazafi Veray János*.

Around him, life went on.

They gave speeches, they stole and looted, envied and slandered, brokered deals; the wives of currency speculators were driven in carriages to gala performances at the Opera House, bloated directors sped through the city in automobiles with smoking cigars clamped between their lips, in restaurants people listened to gypsy music, in cafés they devoured cakes, in bars the city’s harlot-actresses clinked champagne glasses with English and French officers, in the Orpheum they sang titillating cabaret songs and fox-trotted with decadent grace, in the clubs they bet hundreds of thousands of crowns at a time, on the stock exchange there was hausse and baisse, the value of the mark rose and fell, and they cheated with flour, fat and sugar, with silk, diamonds and alcohol, with love, art and political slogans, with overcoats and sheepskin cloaks – with patriotism and internationalism alike.

Of all this, János knew nothing.

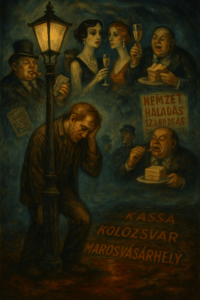

As he pressed his buzzing peasant head each evening against the post of a gas lamp and watched the hopeless swirl unfold, he was, in this faithless country, faithfulness itself; in this rotten city, he was humiliated suffering, innocence hurled into hell, the saintly advocate of the jurist kind, the heavenly prosecutor in the bloodiest trial of world history, the martyr, the herald and the apostle, the bard who could neither sing nor speak, who groaned out his barbaric pain in jarring and graceless rhymes, the awakening of a peasant class left fallow for centuries, the squandered wealth of the East, the aching recollection of a thousand years, the anguish of Komárom, Kassa, Pozsony, Eperjes, Losonc, Szabadka, Temesvár, Arad, Nagyvárad, Kolozsvár, Marosvásárhely — the death-cry forever trapped in the nation’s throat.

He was the Hungarian poet.”

*Translator’s note: Veray was a famous Hungarian folk rhymester of the 19th century.

**Translator’s note: Komárom (Komárno), Kassa (Košice), Pozsony (Bratislava), Eperjes (Prešov), Losonc ( Lučenec), Szabadka (Суботица / Subotica), Temesvár (Timișoara), Arad (Arad), Nagyvárad (Oradea), Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca), Marosvásárhely (Tîrgu-Mureș)

If you like my writings, please feel free to support me with a coffee here:

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon:

Az Égi Jogász

(Kosztolányi Dezső)

“Kaszás-Kis János világéletében napszámos volt. Reggeltől estig talicskázott a határban.

Úgy sírt ez a talicska, mint valami kétéves, beteg gyerek, panaszosan, nagyon szomorúan. Folyton földet vitt benne, kövér, zsíros agyagot, a tanyák alatt, mintha az egész földgolyót föl akarná forgatni és egyik helyről a másikra cepelni, soha véget nem érő, végtelen, kilátástalan munkával.

Ő maga nem vágyakozott többre. Egészséges arca pirosan virított. Azt se lehetett látni rajta, hány éves. Akadtak, akik negyvenötnek nézték, akadtak, akik huszonötnek. Olyan időtelen volt, mint a föld.

Háborúban katonának állt. Kétszer megsebesült, egyszer idegsokkot kapott egy gránáttól. Sokáig remegett ettől a hideg csóktól, mellyel a halál megérintette csöndes parasztfejét.

De mikor leszerelt és visszatért falujába, arca kinyílott, kék szeme nyájasan mosolygott. Akár az alföldi ég, zivatar után.

János talicskázott, mint annakelőtte. Vásott, zöldszürke katonanadrágot hordott, gyűrött civilkalapot. Agyaráról pipa lógott és kedélyesen füstölt.

-Merre járt? – kérdezték tőle.

-Hát a merre a többiek – mondotta.

Acélos, kemény férfitestén nyoma se látszott a fáradalmaknak. Csak éppen hogy nem hízott meg, soha. Szikár maradt a folytonos testi munkában, több száz év alatt – nemzedékeken át – se tudott magára szedni egy latnyi zsírt. Szöghaja dúsan koronázta fejét. De bajusza már nem volt tömött, mintha husának szikes, kavicsos talajában nem lenne elég életerő, hogy ilyen úri díszt is nagyranövesszen.

-Mégis – erősködtek – mit csinátak ott, János bácsi? Hiszen ott vót, vitézségije is van.

-Lüvöldöztünk – szólt és mosolygott.

Nem szerette a sok szót. Dolga-végeztén hazament, viskójába, feleségéhez, meg két kisfiához.

Közben a falu házaira vörös zászlót aggattak, rossz papírszövetből.

Egy augusztusi délután, hogy künn hajladozott a földeken, porfelhőben lovasokat látott feltünedezni, kik vassisakokat és hosszú, zászlós pikákat viseltek. Más oldalról már hallatszott is a recsegő, kietlen trombitaszó, mely valahogy az idegenség és téboly lázát szórta szét az alföldi porba, az akácfák közé.

-A románok – suttogták.

Húsz-harminc ember jöhetett mindössze, egy tiszt vezetésével, meg két szekér, ládákkal, holmikkal.

Bámész emberek, asszonyok, pendelyes gyerekek álldogáltak a községháza előtt és nézték, amint a cigányos, fekete katonák elhelyezkedtek a faluban. Néhány katona szuronyt szegezve megtisztította a teret.

János pipázgatott, a tér oldalán, talicskájára telepedve. Onnan szemlélte nagybölcsen a nép szétszéledését.

Akkor vette észre, hogy feléje is két szuronyos közeledik. Egyik valamit kiabált, románul, nem értette, mit. Aztán mind a kettő hadonászni kezdett, düóhösen. János erre lassan, de tisztességtudóan fölkelt, már nyúlt talicskája után, hogy tovább kászálódjon.

De következő pillanatban arculcsapta, teljes erejéből, a román katona.

Kalapja leesett eléje, a porba.

Óriási riadalom támadt. A falu népe hanyatt-homlok szaladni kezdett, ki merre látott. Az asszonyok sírtak.

-Kaszás-Kis Jánost megütötték – mondták.

-Ájnye – csóválta a fejét egy öreg paraszt -, pedig katona vót, katonaembör…

-Az – mondta a másik -, négy évig. Szögény.

Jánost egy perc alatt öt katona vette körül s már is kísérték befelé, a községházába.

Várt az udvaron, csöndesen, katonák őrizete alatt. Estefelé vezették a tiszt felé.

A tiszt – nagyon fiatal, ápolt hadnagyocska, aki a forró délutánon se vette le vastag, fehér kesztyűjét – egy asztalka előtt ült, egymásra vetett lábakkal és cigarettázott. Tolmács útján hallgatta ki.

-Volt nála fegyver? – szólt a tiszt.

-Nincs kéröm nálam semmi – és már nyúlni akart zsebébe, hogy mutassa.

Most hirtelen lefogták.

-Motozzák meg – mondta a tiszt katonáinak.

Kivettek zsebéből egy pipát, egy piros és szennyes parasztzsebkendőt, egy összegyűrt szovjethuszonötkoronást.

-Othon sincs fegyvere?

-Nincs.

A tiszt két vassisakost küldött lakására, hogy tartsanak nála házkutatást, majd a tolmács felé fordult és hadarva adta ki utasítását:

-Mondja meg neki, ha fegyvert rejteget, azonnal agyonlövik. A töltényeket is ki kell szolgáltatni. Ha puskát, revolvert, kardot tud valaki másnál, árulja el, különben … Ijesszen rá.

Künn a falu már eltemetkezett a nyári éjszakába, katonák jártak szerteszét. Senki se tudta, mi lesz.

A járőr visszajövet jelentette, hogy nem lelt nála fegyvert. Erre a tiszt mondott valamit a tolmácsnak s Jánost hazanegedték.

Fejére nyomta kalapját és szédülve, lesunyt fejjel bakalázott a sötét utcán, hazafelé. Nem volt italos ember, de most úgy érezte, hogy részeg és lába tántorog. MIndenki aludt már. Fekete ablakok meredeznek rá. Csak fönn az augusztusi csillagok szikráztak, villamos fénnyel.

Sápadtan ült meg a küszöbén. Az asszony sírva borult rá.

-Hát möggyütt?

-Mög.

János leült az asztalhoz. Az asszony eléje tette a vacsorát.

-Ögyön.

De nem tudott enni. Félretolta a tálat, leborult az asztalra.

-Önni se tud – mondta az asszony.

-Világi szégyön ez – szólt János.

Akkor fölnyitotta ingét. Mellére mutatott.

Szőrös parasztmellén egy forradás rózsaszín nyoma látszott.

-Itt mönt be a golyó – mutatta.

Újra az asztalra dőlt és száraz, könnytelen sírás rázta hatalmas mellét. De nem tudott sírni. Csak fogát csikorította és valami ugatásféle hallatszott gégéjéből.

– Ne vögye annyira szívére – vigasztalta az asszony. Örüjjön, hogy nem vitték el, rabnak.

-A nyavalyás – zúgta János.

-Óccsa el mán a világot – kérlelte az asszonyt, aki közben vetkőzködött – még meglátják és begyünnek.

Hallgatóztak: a csöndes éjszakában járőrök cirkáltak.

János sokáig nem tudott elaludni, vonyítani szeretett volna a fájdalomtól. Ide-oda hánykódott nyoszolyáján, arcát párnájához szorította. Soha életében nem ütötték meg, katonáéknál sem. Pörlekedésnél pedig mindig a másik húzta a rövidebbet. Egyszer, hogy vitája akadt egy legénnyel és már majdnem ölre mentek, úgy nézett rá, hogy az inkább elsomfordált. Rettenetes szeme volt.

Most lét érdes tenyerét, mely a földmunkától kicserepesedett, arcára borította, megalázva. Jaj, milyen jó, hogy éjszaka hullt rá, sötét, takaró éjszaka. Ez hűtötte szégyenét, mint a hidegborogatás. Körültekintett és boldogan látta, hogy köröskörül minden fekete, az asztal is, a szék is. Csak néha süvített távolból egy puskagolyó.

Reggel kiment a kúthoz. Sokáig mosakodott egy vödör vízben. Még fejét is belemártotta.

-A bal orcámat ütötte mög – mondta az asszonynak – itt – és hozzányúlt, mint egy sebhez.

-Mög se látszik.

-Nem?

-Nem a – erősítette az asszony és összevont szemölddel vizsgálgatta a bal arcát, közelről. Csak mönjön a dógára.

Újra sírt-rítt a talicska. A falu tudta, hogy rendbe jött minden.

Erős nap tűzött a földre, éles, agyvelőthasogató fény. Ezek azok a reggelek, mikor a pusztának már hajnalban láza van. A meddig a szem ellát, por és fakóság, csak itt-ott kiállt véreset egy-egy pipacs. Mezizlábasok kapkodják lábukat a tüzes buckákon, akár parázson táncolnának. Messziről rekedt lárma hallatszik, egy parasztszekér csörömpöl, egy vödör lánca zörög, mely sokáig ér a szomjas kútba. Mintha a homoknak is deliriuma lenne, félrebeszélnek a zajok. Sehol egy foltnyi árnyék a végeláthatatlan sárgaságon. A komondorok már délelőtt nyelvelnek, lehengerednek a földre, mérgesen rágják a sövényt, vagy véres szemmel, behúzott, lompos farokkal sompolyognak, mint az őrültek. Ők is betegek a fénytől.

János egykedvűen ballagdált. Szemére húzta kalapja karimáját, a földre nézett.

-Aggyon Isten – köszöntötte egy ember.

Ő azonban félretekintett, pironkodva. Rejtegette gyalázatát.

-Mer nem vót igazsága – magyarázta az asszonynak, ha ő román, én magyar, azér nem szabad megütnie. Nála fegyver, én mög puszta kézzel. De azér szömébe néztem. Meg is mondtam neki, nem bánom, vezessön a fejedelme elé, akar az tegyen igasságot …

-Minek emészti magát. Ami vót, az vót.

Kaszás-Kis János nem mutatkozott emberek előtt. Híre futamodott, hogy mindenkire haragszik.

-Olyan büszke lött – mondogatták a falujabéliek sértődötten -, talán bizom arra olyan nagyon büszke – és nevettek.

-Min épekedik mindig? – kérdezte este az asszony.

-Csak úgy gondókozom.

Sokáig hallgattak, mind a ketten. János szólalt meg.

-Te anyja, hány magyar lehöt a világon? Azt mongyák’, van tizenkétmillió is.

-Nem kendre tartozik az.

-Román, az nincs annyi – mondta János.

-Löhet.

-De francia az sok van. Nagyon sok. Az löhet húsz millió.

János megint elgondolkozott.

-Mög az angol – tette hozzá. Az is sok van. Nagyon sok. Abbú van legtöbb.

-Látott kend angolt?

-Nem láttam egyet se. Csak taljánt. A fronton. Annyit vót, mint a nehésség. Azok a nagy hegyek tele vótak velük. Hej, ha eccör …

-Mit bánja kend a más dógát. Maj’ eligazítják az urak.

Később nem bolygatta ezeket. De azon gondolkozott, mit tegyen, hogy valamiképp elintézze az ügyét, a szégyent, mely rágódott rajta, akárhogy is beszélték a többiek. Azóta többször találkozott a katonával. Közönyösen sétafikált, hosszú szuronyával, a községháza előtt, vagy ült a földön és fehér fogával zöld almát rágott. Értelmetlenül tekintett rá a román, a havasi pásztorok nagy nyugalmával. Talán azt se tudta, ki ez a magyar talicskás. János elképzelte, hogy neki rohan és arcul üti … kétszer … jobb oldalt is … bal oldal is … hosszú, gyapjas fekete hajába csimpaszkodik és rángatja … ordít … üvölt … vagy kést szúr gégéjébe … s a piros vér magasra buggyan … mint a szökőkút … Aztán – mit bánja -, melléje bökheti ő is a szuronyát. Vagy fölkötheti arra az eperfára, mely mellett áll.

Ájulatos gyönyörűség környékezte meg a bosszú gondolatára, úgy, hogy szédülni kezdett s a fához támaszkodott.

Dehát eltünteti-e ezzel az ő világi szégyenét!

Vállat vont és köpött a porba.

Nem érdemes ez se.

Hanem nagyon szeretett egyedül lenni, távol az emberektől, akiket gyűlölt és ha tehette, elkerülte őket, hogy ne vallassák, mint is volt az. Legjobabn érezte magát künn a tarlón, a dülőutakon, hol csak a fagyal nyílt, céltalanul, meg a lila szamártövis.

Amint csorgott arcáról a verejték és leheveredett – pilledten -, egy kazal árnyékába, egyszer-másszor az is megfordult fejében, hogy elutazik innen. Világgá megy, Amerikába, vagy még messzebb. A világ végére, túl az óperenciás tengeren, hol már nincs semmi sem és le lehet lógatni lábát ebbe a semmibe. Milyen nagyszerű is lenne az. Csakhogy ehhez pénz kell, aztán a románok miatt senki sem mozdulhatott.

-Haj, haj -sóhajtozott János, amint talicskája ütemesen nyikorgott.

Aztán hozzátette magában: -Mögesett a baj.

Egyszer Péter is vele talicskázott, a félszemű rokkant.

Mendegéltek egymás mellett.

János egyszerre felkiáltott boldogan:

-Haj, haj, haj, mögesött a baj, baj, baj – és mjandem kielégülten nevetett.

Péter ránézett. Aztán megkérdezte:

-Hogy van az, János?

-Hát csak úgy, ahogy mondom.

-Hogy te?

-Hát csak úgy. Haj, haj, mögesött a baj, baj.

-Micsoda baj, te?

-Hát csak az. Mint a mesébe.

Péter elvicsorította száját. Látni lehetett csempe fogait, meg vértelen ínyét. Ez nála a nevetést jelentette.

-Rámögy, – mondta és ismételte – haj, haj, baj, baj, baj,

-Az ám – intett János is – rámögy az.

-Aztán tucc másat is?

János megvakarintotta a fejét:

-Tudok biz én.

-Hol tanúttad?

-Nem tanúttam sehol. Csak úgy eszömbe jutott.

-No ez jó – szólt Péter – olyan, mint a könyvbe – s vigyorgott és bólintott reszketős fejével, mert ő is hideg csókot kapott a harctéren.

Ennek is híre terjedt. A gazdák körülvették Jánost:

-Hogy is van az, te?

János katonásan haptákba vágta magát, hangosan, szégyenkezés nélkül fújta a rigmust.

A parasztok mosolyogtak.

-No ez jó adja – szólt egyik asszony – versökbe beszél.

-Még mongyon János bácsi, még – unszolták.

János fölhúzta szemöldökét:

“Piros rúzsa, bazsa rúzsa/ Juj de ronda, juj de cefet ez az egész világ!”

Röhögés harsant föl.

-Ez mán nem gyün ki – okoskodott egy paraszt, mikor kissé elcsendesedtek.

-Nem a – mondta János és összeráncolta szűk homlokát.

Olyan gyötrelmesen szomorú volt arca, mintha fájna a feje.

De aztán nekidurálta magát:

“Széna-, szalma koszorú, / Bolond az, ki szomorú…”

Ennek volt legnagyobb sikere. Tapsolták és utána ordították:

“Széna-, szalma koszorú, / Bolond az, ki szomorú…”

-Igassága van – bólintottak -, minek is bánkódni amiatt.

-Csakhogy elfelejtötte – tette hozzá a kasznár.

János csakugyan megengesztelődött, csillapult indulatja. Már olykor szóba elegyedett másokkal is. Elmesélte, mit művelt az olasz fronton, betért a kocsmába, a parasztok szerették őt, mert szóval tartotta a társaságot és mindig tudott valami szívderítőt, mulatságost, képtelent mondani, hol verset, hol találós mesét. Aztán, mikor felöntöttek a garatra, és szemük babonásan parázslott a pálinka mérgétől, megkérték, hogy énekeljen. Pogány rossz hangja volt. Sápító és érctelen, mint a repedtfazéké. Hallása meg semmi. De úgy tudott figurázni, hogy kész mulatság volt hallgatni. Félrecsapta kalapját, arcát csúfságból feszítette, szemével orra hegyére bandzsított. Így gajdolta:

“Száraz tónak nedves partján / Döglött béka kuruttyol. / Möghallja egy süket embör / Ki a vízben lubickol / Ej-haj denevér. / Hármat rikkant az egér.”

A parasztok szájába kövér hahoták puffadoztak, mint óriás gombócok. Dülöngéltek a nevetéstől.

-Még eccör – ordították.

János rekedten kiabált:

-Száraz a torkom.

-Hát kend mög – és a gazdag paraszt odabökött a pálinkásüveg felé – fizetöm – mondta önérzetesen.

János felhajtotta a pálinkásüveget, egy kortyra.

-Ne te ne! – rikácsolt János – ez volt a szavajárása, hogy vadítsa magát – ne te ne! – és botjával végigvágott a kocsmaasztalon. Az üvegek csörömpöltek, lehulltak a földre.

Fölmászott az asztalra és úgy bőgte torkaszakadtából.

Ilyen mulatságok után hajnaltájt vetődött haza, holtrészegen.

Egy éjszaka az asszony hiába várta. Megvirradt és még mindig nem jött. Csak délfelé állított be. De nem volt részeg, csak komor és fontoskodó.

-Hát kend hun kuncsorog egész éccaka?

Nem felelt, hanem aggodalmasan körültekintett. Bezárta maga mögött a konyhaajtót.

Csak aztán mondta az asszonynak, titkolózva, majdnem súgó hangon:

-Möghíttak.

-Ugyan hová a csodába hítták vóna magát? – fanyalgott az asszony. – Talán a kocsmába, hogy az egész éccak devernyázzon?

-Nem -szólt János -, nagy rangot kaptam én, asszony, nagy tisztességöt.

És két kezével nyomkodni kezdte homlokát.

-Az úgy esött – folytatta -, hogy künn űtem a tarlón. Csöndes szép este vót, pipázgatok, és nézöm a csillagokat. Úgy hulldogáltak azok, mint az eső. Hát mit látok? Az ég csak kinyílik, háromfelül, olyan világosság támad. mint fényös nappal és fönn a felhőkbe muzsikát hallok, de olyan erősen, mintha húsz banda húzná eccőrre. Akkó nevemen szólítanak: “Kaszás-Kis János”, mongya valaki. “Jelön” – mondom én, regula szerint. “Te majd a magyarok dógát igazítod, már mint égi jogász” mongya ez a hang. “Igönis” – mondtam én és akkó leburúttam a fődre.

Az asszony szája tátva maradt a csodálkozástól.

-Miket beszél?

-Az ám. Még a szent Dávid is hegedűtt a hódban. Mivel hogy kihirdötték, törvényesen, Kaszás-Kis János ezentúl maga konfiskálja a szögény nép érdökét.

Az asszony letette a kést, mellyel krumplit hámozott, beengedte a konyhába a gyerekeket. Vállat vont és régi, kelletlen hangján szólt urához:

-Kend is jobban töszi, ha másra áll a gondja … Nézze a gyerököket. Az a kisfiú is milyen mazna. Inkább kerösne rá – és könnyet itatott fel köténye szélével.

János nézte a kisfiát:

“Kisfiú, nagyfiú, / Bolond az, ki szomorú.”

-Szavalni, mög cifrázni a szót, azt érti – pirongatta az asszony. De az is bolond ám, aki ilyen marhaságokat beszél.

Az asszony szavának lett némi foganatja. János újra szorgalmasan járt napszámba az uraságához, az uradalomba, hol ebédet, vacsorát is kapott. Ősz felé elszakadt régi katonanadrágja. Ekkor a kasznártól szerzett viseltes fekete nadrágot, mely magyaros is volt, meg uras is és kabátot, mely térdét verte. Roppantul kiöltözködött. Paraszt testén olyan furán állott ez a maskara, hogy akik meglátták, először elnevették magukat. Ahhoz a madárijesztőhöz hasonlított tudniillik, mely a cseresznyefáktól riogatja a torkos madarakat.

János nem sokat törődött ezzel. Mindig újságot silabizált. Nehezen ment az olvasás, de ebbe is belejött. Otthon munkához látott. Katonaládájára papírokat teregetett, ácsplajbászát, mely évek óta hevert az asztalfiában, meghegyezte konyhakéssel és ákom-bákom betűkkel leírta azt, ami fejében motoszkált. Többnyire versek voltak ezek, meg rajzok. Nagy papirosra külön lerajzolta az Égi jelenést, a Napot, a Holdat, – ezeket sárga ceruzával kiszínezte -, aztán piros sávot pingált, mely a cseheket és a szerbeket jelképezte, az egész fölé pedig hatalmas piros-fehér-zöld Ászlót remekelt.

Zél derekán cihelődni kezdtek a faluból a románok. Hogy kivonultak, a megszállás után, megoldódott a nyelve:

-Hár most mi lösz? – kérdezgették tőle, mert tudták, hogy bötűs ember és úgy szónokol, mint egy képviselő.

Kaszás-Kis János Atilláról, Szent Istvánról, Mátyás királyról beszélt, de Wilsonról és Clemenceauról is tudott már mindent.

-Csak az lösz majd – folytatta-, hogy összegyün mindön magyar. De mindön magyar, aki csak él a főd hátn. Oszt mögalakítják közös határozással a népek ligáját, vagyis hogy a fő-fő törvényt. Népszavazás lösz. Demokrácia, az is lösz. Akkó kiderül a magyarok igassága, már hogy nem ők vótak a hibásak és elkövetkezik az igazi háború, ami még nem vót. Mindönkinek része lösz benne. Még a kismagyar gyerekök is ott ügyenek majd, de csak hátú. Azok szödik föl a golyót, amit kilű az ellenség, mög a kapszlit, ami a fődre potyog, mer akkó semminek se szabad kárbaveszni.

-Hunnét tudja ezt, János bácsi?

-Mögjelentötték neköm, már mint égi jogásznak, hivatalosan.

Bólintottak az emberek.

Felhozták, hogy már igazságot kérhet, azért, amiért arcul ütötte az a román katona. De ő úgy tett, mintha nem hallotta volna. Vagy talán már nem is értette. Olyan messze volt. Túl az óperenciákon, a semminél, mely megvigasztalta.

Februárban a felesége sírva járt a községházán. Azon panaszkodott, hogy az ura eltűnt katonaládájával, meg félretett pár koronájával együtt. A faluban azt beszélték, hogy megháborodott az elméje. Már holt hírét is költötték.

Úgy esett, hogy egy reggelen – se só, se beszéd – gyalogszerrel az állomásra ment. Pörge kalapja mellé árvalányhaj-bokrétát tűzött, kezében rövidszárú fokost szorongatott. Harmadosztályú kocsiba szállt és szónoklatokkal, tréfás versezetekkel Budapestig mulattatta útitársait, kik ökrendeztek a nevetéstől.

Budapesten egy hét múlva a pályaudvarok táján tűnt föl. Itt árulgatta verseit, zöld, piros szalmapapiroson, az Égi Jelenés és a Hazám címűt, de nem igen volt keletjük. Csak menekültek vásároltak, akik – szegények -, mindent megvettek, amitől jó hírt reméltek.

János arca most is piros-pozsgás volt, szeme zavartalanul kék, szava ejtése paraszti és ízes, példaképe a fajtájának, mely annyira bölcs és józan. hogy szenvedésében is úri mértéket tart, őrületében is ügyel méltóságára.

Kabátjára, baloldalt – a szíve fölé – nemzetiszín szalagot varrt keresztalakban. Ha kérdezték, miért, ezt feleltte:

-Mivelhogy Krisztus urunkat is körösztre feszítötték.

Délelőttönként nyakába vette a várost. Válláról foltos, ütött-kopott paraszttarisznya lógott, melybe kenyeret tett, papirokat és a Rajzot, melyen oda van írva a Nap, a Hold és az Ászló. Ezt akarta bejelenteni mindenütt, minisztériumokban, hivatalokban, lapok szerkesztőségeiben, “miszerint hivatalosan is vögyék tudomásul és tétessék határozatba mindön magyarnak ártatlansága”.

-Begyakoroltatván az igasságtövésbe, mint hitelös, égi jogász hirdetöm és perhoreszkálom a népek törvényeit -mondotta.

De amint kiteregette írásait és tovább beszélt, kedves alföldi szavain átütközött valami idegen és lidérces láng, melytől a hallgatók megdöbbentek. Pár koronát vetettek neki. Később azt se adtak. Szolgák, ajtóállók karjánál fogva vezették ki ezt a magyar parasztot és sarkára csapták az ajtót.

Akkor bolyongani kezdett a városban. Mint a bitang kuvasz, a parasztkutya, mely kócosan-borzasan, a megveszéshez közel fut-fut hazátlan és nem találja helyét sehil, csatangolt az idegen városok aszfaltján. Kalapját elhagyta valahol. Hajadonfőtt járkált és utcapadokon hált. Egy éjszakai hajszán elfogta a rendőrség s mert nem tudta magát igazolni, két napig fogvatartotta. Haza akarták toloncolni. János, mint menekült, vagonban kapott szállást. Itt irkált mindenféle szomorú és vidám versezeteket, melyeket utcán jártában hangosan mondogatott.

Ruhája hónapok multán cafatokban lógott testéről, hajtókáját belepte a piszok. Egyszer egy kispesti kocsmában megverték és kirúgták az ajtón. Orrán sokáig látszott két véres csík. Az emberek megálltak a fűzfapoéta előtt, aki valamit hasonlított Hazafi Veray Jánoshoz és nézték.

Körötte pedig folyt az élet. Szónokoltak, loptak, raboltak, irigykedtek és rágalmaztak, üzleteket kötöttek, a valutaüzérek feleségei díszelőadásra hajtattak az Operaházba, a pöffedt igazgatók szájukban füstölgő szivarral vágtattak gépkocsijukon, a vendéglőkben cigányoztak, a kávéházban tortát ettek, a bárban a város ringyó-színésznői angol és francia tisztekkel pezsgőztek, az Orfeumban csiklandós kuplékat daloltak és fox-trottot lejtettek, a klubban százezerkoronás bankokat húztak ki egy tétre, a tőzsdén hausse és baisse volt, a márka árfolyama emelkedett és esett és csaltak liszttel, zsírral és cukorral, selyemmel, gyémánttal és szesszel, szerelemmel, művészettel és politikai jelszavakkal, kabáttal és gubával, magyarsággal és nemzetköziséggel egyaránt.

János minderről semmit sem tudott.

Amint esténként zúgó parasztfejét egy gázlámpáshoz nyomta és nézte a reménytelen kavargást, ő volt ebben a hűtlen országban a hűség, ő volt ebben a rothadt városban a megalázott szenvedés, a pokolba hullajtott ártatlanság, a jogászfajta szent prókátora, a leggyilkosabb világtörténelmi pör égi fiskálisa, a vértanú, kürtös és apostol, a dalolni és szólni nem tudó igric, aki csikorgó-ízetlen rigmusokban jajgatja ki barbár fájdalmát, a századokig parlagon hagyott parasztság magáraocsúdása, az eltékozolt napkeleti gazdagság, egy évezredre nyúló sajgó visszaemlékezés, Komárom, Kassa, Pozsony, Eperjes, Losonc, Szabadka, Temesvár, Arad, Nagyvárad, Kolozsvár, Marosvásárhely keserve, egy nép ki nem szakadható halálordítása.

Ő volt a magyar költő.”

Let me add the French translation

by François Gachot et Paul Rónai

(NOUVELLE REVUE DE HONGRIE 1934)

L’avocat céleste

Par DÉSI RÉ K O S Z T O L Á N Y I

“JEAN KASZÄS-KIS ÉTAIT, depuis sa jeunesse, un journalier. Du matin au soir il poussait sa brouette dans les confins de son village.

Cette brouette pleurait comme un petit enfant malade, plaintivement, avec beaucoup de tristesse. Jean y transportait sans cesse de la terre, une argile grasse et lourde, le long des fermes: on aurait dit qu’il voulait bouleverser le globe entier, le transporter d’un endroit à l’autre, par un travail interminable, infini, désespéré.

Il n’en demandait pas davantage. Son visage s’épanouissait, rouge de santé. On ne pouvait pas dire l’âge qu’il avait. Certains lui donnaient quarante-cinq ans, d’autres vingt-cinq. Il n’avait pas

d’âge, tout comme la terre.

Pendant la guerre, il s’était engagé. Blessé à deux reprises, il avait eu un choc nerveux à la suite de l’explosion d’une grenade. Pendant longtemps encore, il avait tremblé à cause de ce baiser froid que la mort avait déposé sur sa tête calme de paysan. Mais dès qu’il eut ôté l’uniforme et qu’il put rentrer dans son village, son visage s’épanouit, ses yeux bleus reprirent leur doux sourire, tout comme le ciel de la plaine après l’orage.

Il se remit à pousser sa brouette comme jadis. Il portait une culotte militaire usée, d’un gris verdâtre, et un chapeau ordinaire, bien fripé. Il fumait cordialement une pipe qui pendait de sa bouche.

— Quels pays avez-vous vus? — lui demandait-on.

— Les mêmes qu’ont vus les autres — répondait-il.

Son corps endurci, à ressorts d’acier, n’offrait pas la moind retrace de fatigue. Tout au plus n’avait-il jamais engraissé. Il était resté sec par suite de son perpétuel travail physique: pendant descentaines d’années, à travers tant de générations, il n’était pas parvenu à s’engraisser fût-ce d’une once. Ses cheveux noirs formaientune couronne abondante autour de sa tête. Mais sa moustache n’était point touffue, comme pour montrer que le sol aride, marneux de sa chair n’avait pas assez de force vitale pour faire pousser un ornementaussi seigneurial.

— Mais pourtant — lui demandait-on avec insistance — qu’est-ce que vous « y» avez fait, oncle Jean? — Vous y étiez, vous, puisque vous avez même la médaille militaire.

— On s’est tiré dessus — répondait-il et il souriait.

Il n’aimait pas beaucoup parler. Son travail terminé, il rentrait dans sa cabane, auprès de sa femme et de ses deux fils.

Entre-temps, on hissa sur les maisons du village des drapeaux rouges, d’une mauvaise toile en papier.

Un après-midi d’août, pendant qu’il s’affairait à son travail, dans les champs, d’un nuage de poussière il vit émerger des cavaliers qui portaient des casques de fer, et de longues piques ornées de flammes.

D ’un autre côté du pays, on entendait, déjà, le son strident et assourdissant des trompettes qui répandait la fièvre de la nervosité et de la folie dans la poussière de la plaine, parmi les acacias.

— Les Roumains — chuchotait-on.

Vingt à trente hommes en tout venaient d’apparaître, conduits par un officier, accompagnés de deux voitures chargées de caisses et de différents autres objets.

Des hommes curieux, des femmes, des enfants en chemise badaudaient devant la mairie et regardaient les soldats au visage brun, un peu semblables à des tziganes, se disperser dans le village. Quelques soldats, baïonnette au canon, procédèrent au dégagement de la place.

Au bord de la place, Jean fumait sa pipe, assis sur sa brouette.

De là, il contemplait avec une sagesse tranquille les gens qui se dispersaient.

Il s’aperçut soudain que deux soldats s’approchaient de lui. L’un d’eux lui cria quelque chose en roumain, mais qu’il ne comprit pas.

Là-dessus, tous deux se mirent à agiter le bras avec fureur. Ce voyant, Jean se leva avec lenteur, mais respectueusement, et il saisit les brancards de sa brouette pour aller son chemin. Mais à ce moment, un des soldats lui asséna un coup vigoureux sur la figure.

Son chapeau tomba devant lui, dans la poussière.

Ce fut la panique. Les gens du village se sauvèrent à toutes jambes, û qui mieux mieux. Les femmes pleuraient.

— On a frappé Jean Kaszás-Kis — dirent-elles.

— Oh là là — s’exclama un vieux paysan — c’est un ancien

soldat. . . Il a pourtant fait la guerre.

— Pendant quatre ans — ajouta un autre. — Le pauvre!

En moins d’une minute, Jean fut entouré de cinq soldats qui l ’emmenèrent à la mairie.

Il attendit dans la cour, en silence, sous la garde des soldats.

Vers le soir, on le conduisit devant l’officier.

Celui-ci, un petit lieutenant très jeune, à l’extérieur soigné, qui malgré la chaleur torride de l’après-midi n’enleva point ses épais gants blancs, était assis à une petite table et, les jambes croisées, fumait une cigarette. Il procéda à son interrogatoire avec l’aide d’un interprète.

— A-t-on trouvé des armes sur lui? — demanda-t-il.

— Mais non, je n’ai rien sur moi, s’il vous plaît — et Jean allait enfoncer les mains dans ses poches pour en montrer le contenu.

On le saisit.

— Fouillez-le! — ordonna l’officier à ses soldats.

On trouva dans ses poches une pipe, un mouchoir sale de paysan, î-o u g e , un billet de vingt-cinq couronnes froissé.

— N’a-t-il pas d’armes sur lui?

— Non.

L’officier envoya chez Jean deux soldats casqués pour y opérer une perquisition, puis, se tournant vers l’interprète, il communiqua ses ordres sur un ton précipité.

— Dites-lui que s’il cache des armes, on va le fusiller sur le champ. Il devra livrer aussi les cartouches. S’il connaît des gens possédant des fusils, des revolvers, des épées, qu’il les dénonce, ou bien . .. Effrayez-le.

Au dehors, le village déjà s’était enseveli dans la nuit d’été. Des soldats parcouraient les rues, personne ne savait ce qui adviendrait.

De retour, les hommes de la patrouille annoncèrent qu’ils n’avaient pas trouvé d’armes au domicile de Jean. Sur ce, l’officier dit un mot à l’interprète et Jean fut relâché.

Enfonçant son chapeau sur son front, la tête basse, dans un vertige, il se mit en route vers sa maison dans la rue sombre, à pas incertains. Il n’était pas un ivrogne, mais cette fois il avait l’impression qu’il était gris et que ses jambes chancelaient. Tout le monde dormait.

Des fenêtres noires le dévisageaient. Seules les étoiles d’août étincelaient là-haut, avec une lueur électrique.

Pâle, il s’arrêta sur le seuil de sa porte. Sa femme l’embrassa en pleurant.

— Vous êtes donc revenu?

— Oui.

Il s’assit à la table. Sa femme apporta le dîner et le disposa devant lui.

— Mangez donc.

Il ne put manger. Il repoussa le plat et laissa tomber sa tête sur la table.

— Vous ne pouvez même plus manger — dit la femme.

— C’est une honte publique — répondit-il.

Il ouvrit sa chemise et montra sa poitrine.

Sur cette poitrine hirsute de paysan il y avait la trace rose d’une cicatrice.

— C’est là que la balle est entrée — dit-il en la montrant.

Il retomba de nouveau sur la table et sa puissante poitrine fut secouée d’un sanglot sec, sans larmes. Il ne réussit pas à pleurer.

Seules ses dents grincèrent et une sorte d’aboiement sortit de sa gorge.

— Ne vous en faites pas tant que ça — dit la femme pour le consoler.— Soyez content qu’ils ne vous aient pas entraîné comme esclave.

— Le misérable! — murmura Jean.

— Allumez donc la lampe ! — fit-elle, tout en se déshabillant. —

Ils vont voir la lumière et vont entrer encore.

Ils écoutèrent. Des patrouilles circulaient dans la nuit muette.

Pendant longtemps, Jean ne put s’endormir. Il aurait voulu hurler de douleur. Il se vautra sur son lit, en pressant l’oreiller contre sa joue. Jamais de sa vie on ne l’avait frappé, même pas chez les soldats.

Dans les querelles, ç’avait toujours été lui qui l’emportait. Un jour qu’il avait eu une altercation avec un gars avant d’en venir aux mains, il l’avait toisé d’une telle manière que l’autre s’en était allé tout penaud.

Il avait des yeux terribles.

Humilié, il couvrit ses joues de ses deux mains calleuses, endurcies par les travaux de la terre. Quelle chance, mon Dieu, qu’une nuit noire et dense fût tombée sur lui. Cela rafraîchissait sa honte comme une compresse froide. Il jeta des regards tout autour et constata avec joie que la table, la chaise, tout était noir. De temps en

temps on entendait au loin siffler une balle.

Le matin il se rendit au puits. Dans un seau il se lava longuement et se trempa même la tête dans l’eau.

— C’est ma joue gauche qu’il a frappée — dit-il à sa femme — ici — et il montra la trace de l’affront comme une plaie.

— Ça ne se voit pas.

— Non, vraiment?

— Mais non — confirma la femme, en examinant la joue gauche de son mari, penchée sur lui, les sourcils contractés. — Allez tranquillement à vos affaires.

De nouveau, la brouette se remit à grincer, à pleurer. Le village sut que tout était rentré dans l’ordre.

Un soleil vigoureux dardait sur la terre des rayons aigus, à fendre les cerveaux. C’était un de ces moments où la puszta a de la fièvre dès le matin. A perte de vue, de la poussière, des taches grises: çà et là seulement, quelque coquelicot lançait un cri sanglant. Des vanu-pieds se hâtaient de soulever leurs talons des mottes brûlantes

comme s’ils dansaient sur de la braise. Du lointain, parvenaient des bruits rauques: le cahot d’un charriot de paysan, la chaîne d’un seau qui avait de la peine à atteindre le fond d’un puits assoiffé. Comme si le sable lui-même était dans le coma, les bruits déliraient. Nulle part, dans l’infini jaune, une tache d’ombre. Dès le matin, les chiens étaient hargneux, se vautraient par terre, mordillaient furieusement la haie, ou se faufilaient comme des fous, les yeux injectés de sang, rentrant leur queue hirsute sous le ventre. La lumière les rendait malades eux aussi.

Jean cheminait indifférent. Son chapeau rabattu sur les yeux, il regardait la terre.

— Bonjour! — le saluait-on.

Mais il regardait de côté, honteux, comme pour cacher sa honte.

— C’est qu’il n’avait pas raison — expliquait-il à sa femme. —

Q u’il soit Roumain et moi Hongrois, ce n’est pas là une raison pour me frapper. Il était armé, moi, je n’avais rien dans la main. Mais je l’ai bien regardé dans les yeux. Je lui ai dit qu’il pouvait me conduire devant son roi, s’il le voulait; que le roi lui-même fasse justice . . .

— Allons, ne vous en faites pas. Ce qui s’est passé, est passé.

Mais Jean ne voulait pas se présenter devant les hommes. On commença à raconter qu’il en voulait à tout le monde.

— Il est devenu très fier — se disaient les gens du village, froissés.

— On voudrait vraiment savoir de quoi. Est-ce peut-être de ce qu’il a reçu? — et ils riaient à gorge déployée.

— Pourquoi vous faites-vous toujours du mauvais sang? — lui demandait le soir sa femme.

— Je réfléchis, tout simplement.

Ils se taisaient longtemps, l’un et l’autre.

— Dis, la mère, combien de Hongrois peut-il bien y avoir dans le monde?

— On dit qu’il y en a douze millions. Mais cela ne vous regarde pas.

— Des Roumains, il n’y en a pas tant que ça — dit Jean.

— C’est possible.

— Mais des Français, il y en a beaucoup, beaucoup, beaucoup.

Il peut y en avoir vingt millions même.

Il se replongea dans ses pensées.

— Et des Anglais aussi, il y en a beaucoup. Il y en a plus que de tous les autres.

— Avez-vous vu un Anglais?

— Non, je n’en ai jamais vu. J ’ai vu seulement des Italiens, au front. Il y en avait des masses. Toutes ces grandes montagnes en étaient pleines. Mon Dieu, si un jour.. .

— Ne vous mêlez pas des affaires des autres. Les messieurs s’en occuperont.

En effet, il finit par abandonne rces pensées. Mais il ne cessait de réfléchir à ce qu’il devait faire pour réparer l’affront, la honte qui le dévorait, quoi qu’eussent dit les autres. Depuis ce jour, il rencontra le soldat plusieurs fois. Celui-ci se promenait indifférent, sa longue baïonnette au canon, devant la mairie où il était assis par terre

et de ses dents blanches mastiquait une pomme verte. Il regardait Jean sans comprendre, avec le calme extraordinaire des pâtres des glaciers. Peut-être ne savait-il même pas qui était ce brouettier hongrois. Jean se voyait en pensée se ruer sur lui, le frapper . . . deux fois même . . . la joue gauche et la joue droite . . . empoigner ses longs cheveux noirs et laineux, les houspiller . . . crier .. . hurler . . . lui enfoncer un couteau dans la gorge . . . Le sang rouge jaillirait. . .haut comme une fontaine . . . Ensuite — que lui importait? — l’autre pourrait le percer de sa baïonnette ou même le pendre au mûrier qui s’élevait à côté de lui.

A la pensée de la vengeance, il faillit s’évanouir de joie: il eut le vertige et s’appuya contre un arbre pour ne pas tomber.

Mais est-ce que cela aurait fait disparaître sa honte à lui?

Il haussa les épaules et cracha dans la poussière.

Cela non plus ne valait pas la peine.

L’amour de la solitude le prit. Il voulut être loin des hommes qu’il haïssait et, autant qu’il le pouvait, il les évitait pour ne pas être interrogé sur ce qu’il appelait sa honte. C’est dans les chaumes qu’il se sentait le mieux à son aise et dans les sentiers où fleurissaient, sans but et sans raison, le troène et le chardon violet.

Pendant que la sueur coulait de son front et qu’il se laissait choir, fatigué, à l’ombre d’une meule de foin, quelquefois il lui venait à l’idée de quitter le pays, de partir pour l’Amérique ou plus loin encore, au bout du monde, près de la mer océane, là où il n’y a plus rien et où l’on peut s’asseoir au bout du néant, les jambes ballantes. Ça aurait été en effet magnifique. Seulement cela demandait de l’argent, et puis les Roumains ne laissaient bouger personne.

— Ça. y est! — disait-il en poussant de gros soupirs pendant que sa brouette grinçait au rythme de la route.

Et il ajoutait en lui-même:

— Le malheur est fait.

Un jour Pierre, le mutilé borgne, poussait sa brouette à côté de la sienne.

Ils cheminaient côte à côte.

Soudain Jean s’écria, tout heureux:

— Ça y est, ça y est, le malheur est fait — et il rit presque avec satisfaction.

Pierre le regarda. Au bout d’un instant, il demanda:

— Dis voir, Jean, qu’est-ce que tu disais-là?

— Pas grand’chose.

— Dis t o u j o u r s .

— Eh bien, je disais: Ça y est, le malheur est fait.

— Quel malheur?

— L e m a l h e u r , q u o i , c o m m e d a n s l e s c o n t e s .

Pierre tordit la bouche. On voyait ses dents ébréchées et ses gencives exsangues. Chez lui, cette grimace signifiait le rire.

— Ça sonne bien à l’oreille — dit-il, en répétant: Ça y est, ça y est, le malheur est fait.

— Pour ça, oui — dit Jean; ça sonne bien.

— En sais-tu d’autres comme ça?

Jean se gratta la tête.

— Bien sûr que j ’en sais.

— Où as-tu appris ça?

— Je ne l’ai appris nulle part. Ça m’est venu à l’idée tout seul.

— C’est drôle — dit Pierre — on dirait que c’est d’un livre.

E t il ricana de nouveau, en dodelinant la tête car lui aussi il avait eu le « baiser froid » de la mort, sur le champ de bataille.

Cela aussi, on l’apprit bientôt. Les paysans entourèrent Jean.

— Dis un peu ce que tu as fabriqué?

Militairement, Jean se mit au garde-à-vous et récita son dicton à haute voix, sans embarras.

Les paysans sourirent.

— Il est drôle celui-là — dit une femme — il parle en vers.

— Dites-en d’autres, oncle Jean! — disaient les autres.

Jean haussa les sourcils:

« Rose rouge, pivoine blanche,

Ce que le monde est dégoûtant ! »

Des éclats de rire fusèrent.

— Oui, mais ça ne fait pas un vers — remarqua un paysan quand le silence se fut rétabli.

— Oui, c’est vrai — concéda Jean en fronçant son front étroit.

Son visage exprima une véritable douleur comme sous le serrement d’une migraine.

Puis, en donnant un coup de collier:

«P aille des champs, foin des champs,

C’est fou de s’faire du mauvais sa n g. . . »

Ces vers eurent un succès extraordinaire. Les autres applaudirent et hurlèrent avec lui:

«Paille des champs, foin des champs,

C’est fou de s’faire du mauvais sa n g. . . »

— Il a raison — disaient-ils en branlant la tête — à quoi bon se manger le sang à cause de ça.

— Heureusement qu’il a oublié — ajouta l’intendant.

En effet, Jean se rassérénait, ses passions se calmaient. De temps à autre, il nouait conversation avec les paysans. Il entrait au cabaret, racontait ce qu’il avait fait au front italien. Les autres l’aimaient car il savait toujours leur débiter quelque chose de drôle et d’amusant, soit des vers, soit des devinettes. Puis, quand ils avaient levé le coude et que le poison de l’eau-de-vie avait embrasé leurs yeux d’une lueur sinistre, ils le priaient de chanter. Il avait la voix désagréable: criarde, détimbrée, de pot cassé. Avec cela, pas d’oreille. Mais il savait blaguer que c’était un plaisir de l’entendre. Il mettait son chapeau sur l’oreille, se décomposait le visage pour faire rire les autres, louchait et se mettait à chanteronner :

« Sur le bord humide d’un lac desséché

Une grenouille crevée se met à coasser,

Un sourd en train de se frétille r

D e l’eau entend la grenouille coasser

Tintin, tirlin tin tin,

L a chauve-souris chante joyeusement. »

Les paysans pouffaient de rire et se tenaient les côtes.

— Bis! — hurlaient-ils.

Enroué, Jean leur criait:

— J ’ai la gorge sèche.

— Tu n’as qu’à la mouiller — lançait un paysan riche, en indiquant du doigt la bouteille à eau-de-vie et en ajoutant avec fierté:

C’est moi qui paie.

En une lampée, Jean vida la bouteille.

— Va bigre! — hurla Jean (c’était son mot favori quand il voulait s’abrutir) — va bigre! — et il asséna un vigoureux coup de bâton sur la table. Les verres cliquetèrent, tombèrent par terre.

Il grimpa sur la table et hurla à tue-tête.

Après de telles bombances il rentrait vers l’aube, ivre-mort.

Une nuit, sa femme l’attendit en vain. Le jour vint sans que Jean fût rentré. Enfin il parut à midi. Au lieu d’être ivre, il n’était que morne et il se donnait des airs.

— Où diable vous traînez-vous toute la nuit?

Il ne donna point de réponse. Après avoir jeté un regard méfiant tout autour, il referma sur eux la porte de la cuisine.

Ce ne fut qu’ensuite qu’il confia à sa femme, tout bas, d’une voix faible comme un soufflle:

— On m’a invité.

— Invité, où diable? — dit la femme, ombrageuse. — Au cabaret sans doute, pour y faire la noce?

— Non — répondit Jean — on m’a promu à un grand honneur, à un haut rang.

De ses deux mains, îl se mettait à se pétrir le front.

— Ça c’est fait comme ça — reprit-il. — J ’étais assis dans les

chaumes. Le soir était beau, je fumais ma pipe et je regardais les étoiles. Elles tombaient dru, comme la pluie. Tout à coup, qu’estce que je vois? Le ciel s’ouvre de trois côtés, il fait clair comme en plein jour et là-haut, dans les nuages, j ’entends de la musique, mais forte, comme si vingt orchestres jouaient à la fois. On m’appelle par

mon nom: « Jean Kaszás-Kis » qu’on me dit. « Présent » dis-je, comme de juste. « Tu auras à régler l’affaire des Hongrois, en tant qu’avocat céleste» me dit la voix. « Comme il vous plaira» — que je dis etje me suis prosterné par terre.

La femme l’écoutait bouche-bée.

— Qu’est-ce que vous dites là?

— Mais oui, c’était comme ça. Saint-David lui-même jouait de son violon dans la lune. C’est qu’on a proclamé par la loi que Jean Kaszás-Kis doit désormais lui-même tâcher moyen de défendre l’intérêt des pauvres gens.

La femme posa le couteau avec lequel elle épluchait des pommes de terre et laissa entrer ses enfants qui arrivaient dans la cuisine. Elle haussa les épaules et adressa la parole à son mari de sa voix acariâtre,

sa voix habituelle.

— Vous feriez mieux de penser à autre chose . . . Regardez les gosses. Ce qu’il est maigrelet ce petit. Vous devriez plutôt gagner pour lui . . . — et du coin de son tablier elle essuya une larme sur son visage.

Jean contempla son enfant.

«P etits enfants, grands enfants,

C’est fou de s’faire du m auvais sang. »

— Pour ça, vous êtes fort — dit-elle en le rudoyant: — débiter des bêtises et retourner les mots en chaque sens. Faut être timbré pour faire ça . . .

Ses reproches eurent quelque effet. De nouveau, Jean alla en journée régulièrement au domaine du seigneur du village où on lui donnait aussi à déjeuner et à dîner. En automne, son vieux pantalon militaire montra la corde. De l’intendant, il obtint alors un pantalon noir usé, taillé à la hongroise et faisant en même temps très « grand

seigneur » et un veston qui lui battait les genoux. En un mot, il s’endimanchait. Ce travesti faisait, sur son corps de paysan, un effet si drôle qu’il faisait rire tous ceux qui l’apercevaient pour la première fois. Il ressemblait à l’épouvantail qui défend aux oiseaux gloutons l’abord des cerisiers.

Jean ne s’en souciait guère. Sans cesse, il déchiffrait des journaux.

La lecture n’était pas facile au début, mais il finit par s’y habituer.

Chez lui, il se mit à l’ouvrage. Sur sa cantine de soldat, il étendit des feuilles de papier, tailla avec le couteau de ménage son crayon de charpentier qui depuis des années était oublié dans le tiroir, et avec des pattes de mouche, il coucha sur le papier ce qui lui passait par la tête. C’étaient pour la plupart des vers et des dessins. Sur une grande feuille, il dessina Y Apparition Céleste, le Soleil et la Lune, les colora d’un crayon jaune, puis traça une raie rouge symbolisant les Hongrois, une bleue symbolisant les Roumains et une verte indiquant les Tchèques et les Serbes, et, au-dessus du tout, un énorme Drapeau rouge-blancvert.

Vers le milieu de l’hiver, les Roumains se préparèrent au départ.

Quand, l’occupation terminée, ils eurent quitté le village, cet événement délia la langue à Jean:

— Eh bien, qu’est-ce qu’il y aura maintenant? — lui demandait-on, car on savait qu’il connaissait ses lettres et qu’il pérorait comme un député.

Jean parlait d’Attila, de Saint-Etienne, de Mathias Corvin, mais il savait tout ce qu’il fallait savoir sur Wilson et sur Clemenceau également.

— Il y aura que tous les Hongrois vont se réunir, mais tous ceux qui vivent sur cette terre. De commun accord, ils vont créer la Ligue des Peuples, c’est-à-dire la grande loi. Il y aura aussi du plé biscite. De la démocratie, il y en aura de même. Alors on apprendra la justice des Hongrois, c’est-à-dire qu’ils n’y étaient pour rien dans

la guerre et viendra une autre guerre, la grande, comme il n’y en a jamais eu. Tout le monde y prendra part. Même les gosses hongrois iront surveiller les choses, mais ils resteront en arrière. Ce seront eux qui recueilleront les balles que tirera l’ennemi et les cartouches qui tomberont par terre, car dans cette guerre rien ne devra se perdre.

— Comment le savez-vous, oncle Jean?

— On me l’a annoncé à moi, comme avocat céleste, officiellement.

Les autres acquiesçaient de la tête.

On lui faisait remarquer que désormais il pouvait exiger la réparation de l’affront que lui avait fait le soldat roumain en le frappant.

Mais il faisait semblant de ne pas entendre.

En février, sa femme parut à la mairie, en pleurant. Son mari avait disparu, avec sa cantine de soldat et avec ses quelques couronnes d’économies. Dans le village on racontait qu’il avait perdu la raison.

On colportait même la nouvelle de sa mort.

C’est qu’un matin, sans avertir personne, il avait pris le chemin de la gare, à pied. Il avait attaché un bouquet de plumets de Vaucluse à son chapeau rond, et serrait dans sa main un court bâton ferré.

Monté dans un wagon de troisième classe, il avait amusé ses compagnons de voyage pendant tout le trajet, de son village à Budapest.

Il leur débitait des harangues, des dictons rimés, et ils poussaient de gros rires.

Une semaine après, il émergea à Budapest. On le vit près des gares offrir ses poésies imprimées sur papier pelure vert et rouge.

Mais VApparition Céleste et Ma Patrie ne trouvaient pas beaucoup d’acheteurs. Seuls des réfugiés les achetaient qui, les pauvres, achetaient tout où ils espéraient découvrir quelque bonne nouvelle.

Les pommettes de Jean étaient toujours vermeilles, ses yeux d’un bleu limpide, sa prononciation savoureuse, celle des paysans, son parler un modèle de sa race, sage et modérée au point d’observer la mesure même dans la souffrance, d’avoir soin de sa dignité même dans la folie.

Sur son veston, au-dessus du cœur, il attacha un ruban tricolore, en forme de croix. Lorsqu’on lui demandait pourquoi, il répondait:

— C’est que notre seigneur Jésus-Christ a été crucifié lui aussi.

Le matin, il faisait le tour de la ville. De son épaule pendait une besace rapiécée, bien usée, dans laquelle il portait du pain, des feuilles de papier et le Dessin, représentant la Lune, le Soleil et le Drapeau.

L ’annoncer partout, c’est ce qu’il voulait dans les bureaux des ministères, dans les rédactions des journaux « pour qu’on prenne acte officiellement » et « pour que décision soit portée sur l’innocence de tous les Hongrois ».

— M ’étant exercé dans l’administration de la justice, je proclame

et je solutionne la loi des peuples — déclarait-il.

Mais à mesure qu’il déployait ses feuilles et continuait à parler, à travers ses savoureuses paroles de paysan perçait une flamme étrange, un feu follet qui étonnait les auditeurs. On lui jetait quelques couronnes.