“If the bridge is lost, Transylvania is lost!” (Joseph Bem)

On February 9, 1849, the armies of General Joseph Bem of the Hungarian Army and Anton Puchner, the Imperial commander in Transylvania, fought the decisive Battle of Piski, where, after a bloody struggle, the forces of the Polish-born military leader emerged victorious.

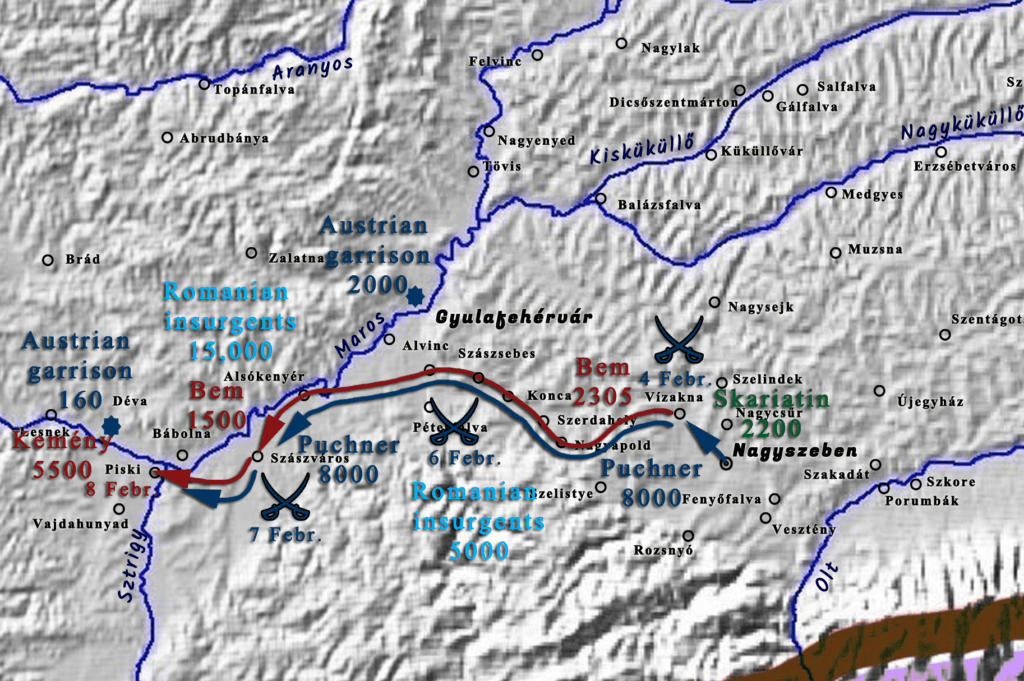

The brilliant Transylvanian campaign, launched in December 1848, reached a turning point after the setback suffered at Nagyszeben (Sibiu), as Puchner soon compelled the Saxon and Romanian national committees to call in the Russian troops stationed in Wallachia. After the Tsarist forces occupied Nagyszeben and Brassó (Brașov), the imperial commander-in-chief could turn his full force against Bem, achieving a significant victory over the honvéds on February 4 near Vízakna (Vizakna).

After this heavy defeat, the “Bloody Star of Ostrołęka” was left with only 1,500 men and a few cannons, leaving him with but one option: to make a quick escape westward, for along the Maros River, significant reinforcements sent to Bem by Damjanich János, who was being pushed out of the Bánság (Banate) region, were moving eastward.

Since Puchner’s forces held an overwhelming advantage, in the following days, the soldiers had to perform nearly superhuman feats, as during their retreat, they fought bloody rearguard actions against the Imperial troops, while the Polish commander-in-chief was essentially incapacitated due to his wounds.

However, Colonel Czetz János, who stepped into Joseph Bem’s place, excelled in the task entrusted to him, so that after a few days, the troops were able to unite with the auxiliary forces sent by Damjanich, thereby increasing the Transylvanian army to 7,000 men. After that, only one, but all the more serious, task remained: they had to stop Puchner’s forces before they could break out onto the Great Hungarian Plain. This occurred during the Battle of Piski, fought on February 9, 1849.

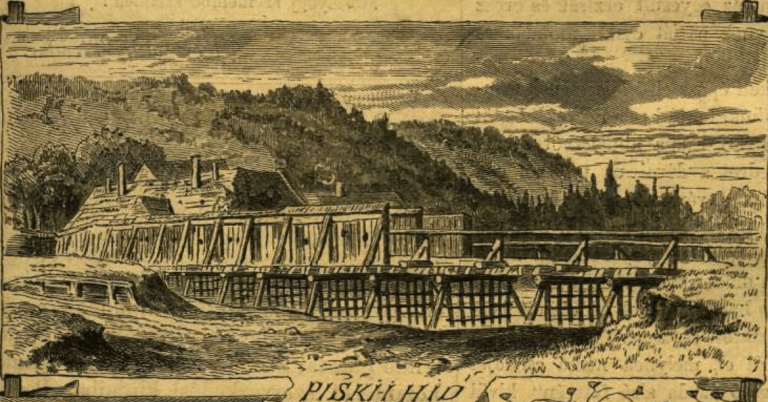

The small village lies 8 kilometers east of Déva, on the left bank of the Sztrigy River, where Bem’s troops had already taken up their positions on the day before the battle, February 8. The task of the Polish-born commander-in-chief was simple and clear: he had to prevent the Imperial forces from capturing the roughly 40-meter-long wooden bridge built over the Sztrigy. As Bem himself stated: “If the bridge is lost, so too is Transylvania,” thus the crossing near Piski later proved to be one of the most significant bridges in Hungarian military history.

To secure success, the general also established strong defensive positions near the inn located on the right bank of the river. However, these were swept away in an instant by the Austrian attack launched at dawn on February 9. Puchner arrived at Piski with a force roughly equal to Bem’s army—about 7,000 regular soldiers. In addition, the Imperial troops were supported by masses of Romanian militia, and the Austrian artillery far surpassed the firepower of the soldiers.

The battle thus began with an Imperial attack. After the troops of Kemény Farkas were pushed back, the Matthias Hussars were sent to charge in vain, as Puchner’s artillery cut the cavalry to pieces within moments. The struggle soon raged directly for the bridge, where, at a critical juncture in the clash, Austrian soldiers even began disarming the Hungarian soldiers. However, the appearance of Czetz reversed the course of events.

The Hungarian forces soon launched a desperate assault against the Imperial troops, who were taken aback by the unexpected resistance and began to retreat shortly thereafter. For a time, Bem’s troops gained the upper hand, but the general advance once again broke before Puchner’s cannons. Under the command of the Austrian commander-in-chief, who had arrived at Piski, the enemy once again reached the Sztrigy.

Fortune thus changed sides once again: the inn situated on the right bank changed hands for the third time within a short period. The situation of the Hungarian soldiers then turned even more critical than before, for while part of the Hungarian troops had already begun to flee, Puchner’s engineers started rebuilding the destroyed section of the bridge so that, after hauling the cannons across, they could deliver a decisive blow to Bem’s remaining forces.

The battle seemed lost. However, the Polish commander noticed that the Imperial troops had almost completely exhausted their ammunition, so he staked everything on one final move: he sent into battle the reserve units under the command of Bethlen Gergely, which ultimately fought their way to victory.

Thus, the bridge connecting the two banks of the Sztrigy remained in the hands of the Hungarians, and in the following months, Transylvania once again came under Hungarian control. It is true, however, that serious feats were still required for the final success, as Bem was only able to return to Székely Land by outmaneuvering Puchner and the Russians, where he could once again refresh his troops and prepare to drive out the enemy forces.

Let me give you some parts from a contemporary description of the battle, by Gaál Mózes:

“Children, one does not usually think back on a retreat like ours from Vizakna to Piski with shame, but with pride. Blood flowed like a stream, and the sound of cannons was music to our ears. Some marauding Wallachian troops crossed our path near Szászváros. We dealt with them as if setting wolves upon a lion. We scattered them and continued on our way. There were no more than fifteen hundred men and two cannons left in the whole army… The rest all perished at Vizakna and during the bloody four-day-long retreat.

Bem halted at Piski. The rest was welcome for us as well, for such respites rarely came our army’s way. We were already near the borderlands of Transylvania. In the distance, the high fortress of Déva was visible, along with the waters of the Maros, gliding through the valley of the Ompoly.

The ice on the Sztrigy stream was churning and crashing against the red brick pillars of the bridge. Father Bem told Colonel Czecz that if it were lost, Transylvania would be lost as well.

But God is good; He helps a man when he is in the greatest need of help. So it happened now.

From Arad, a Hungarian army came to join Bem’s forces. To increase by five thousand soldiers was no small matter.

An indescribable joy seized us. We looked upon the bridge as if it were already ours.

Yet it was now that the hardest task awaited us.

The Austrians began a murderous barrage from the ridge of the opposite hill, and the Matthias Hussars were forced to turn back across the bridge, for otherwise they would have fallen to the last man before reaching the end of the river. Colonel Czecz and Major Kemény Farkas, along with a battalion each, were cut off by the Imperial troops, who demanded they surrender their swords. But the valiant Colonel Czecz, instead of replying, shouted to the soldiers:

“Fix bayonets, and forward!…”

The Austrians stared in astonishment at this miracle and fled from the deadly points of the bayonets—thus did Colonel Czecz break free.

Meanwhile, Father Bem, disregarding the wound he had just received, positioned his cannons and fired into the mass of Imperial troops pursuing the Hungarians. Within the dense throng, they wreaked immense devastation…

“Do not flee, Hungarians!… Do not flee!… Forward, Székelys!” rang the commander’s order, and as if a new spirit had taken hold of everyone—we held our ground, meeting the advancing Austrians in perfect order… The assault did not last long; the attackers soon became fugitives, and the besieged became the pursuers.

Around the bridge lay the dead and mortally wounded; blood dripped onto the churning ice floes of the Sztrigy—but the bridge was ours, it was not lost—and with it, we had also saved Transylvania.

They say, children, that since then a memorial has been erected there to commemorate the day of the Battle of Piski Bridge… I haven’t been back that way since, though somewhere in my leg or wherever I still carry that Austrian bullet that lodged inside… It ached bitterly after the battle, but during the battle, I didn’t feel it…

Perhaps the Austrian didn’t aim for my leg but for my head… The poor fellow missed a little, but no wonder—there was so much smoke around the bridge.”

Consequences

What was the explanation for the Hungarian success and the Imperial failure? The latter is easier to explain. Puchner has miscalculated the number of Hungarians, or rather, he became overconfident in himself. After Bem’s four-day retreat and the losses he suffered in the process, he could not believe that the Hungarian leader would be able to turn the tide of the war. There is hardly any other explanation for leaving three battalions of infantry, three and a half companies of cavalry, and the most valuable part of his artillery, the twelve-pounder battery, in Szászsebes.

Let us recall Görgei’s proposal to Kossuth in April 1849: “Let us give red caps to all those battalions, and other types of military units, which through their continuous bravery have earned the respect and admiration of the world, and the gratitude of the homeland…”

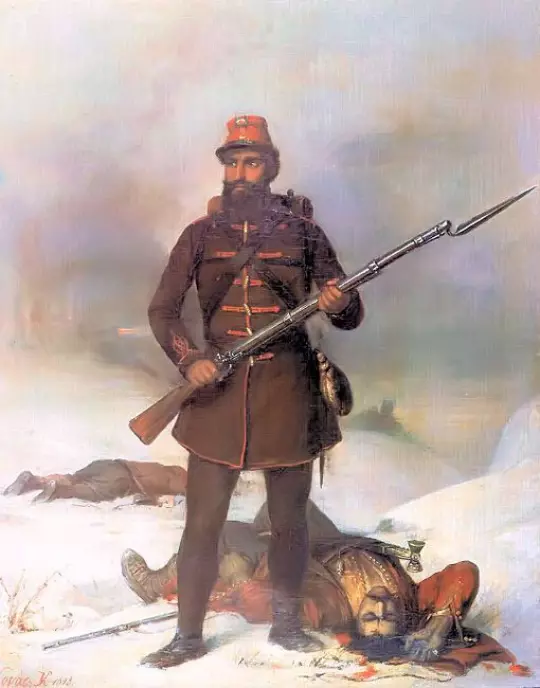

In the Hungarian War of Independence, the legendary 9th Battalion, and later the 11th Battalion, bore the distinctive emblem of the red cap. The 9th Battalion was organized from recruits in Kassa (Kosice, Kaschau) and Miskolc, and they were allowed to retain their red caps due to their outstanding bravery displayed in the southern campaigns led by Damjanich János. For the soldiers of the 11th Battalion, formed in Kolozsvár (Cluj, Klausenburg), General Bem granted them the right to wear the red cap in recognition of their self-sacrificing bravery demonstrated in the Battle of Piski.”

Legacy:

In 1853, the Austrian authorities erected a monument in memory of Cavalry Colonel Ludwig von Losenau, who died in the battle of Piski in the castle of Gyulafehérvár. In 1899, the Hunyad County Historical and Archaeological Society decided to erect a monument in memory of the soldiers from both sides who died in this battle. Unfortunately, this monument was demolished by the newly installed Romanian authorities after the Treaty of Trianon in 1920. Recently (2026), the monument of the fallen heroes has been rebuilt.

/Source: Rubicon and Gaál Mózes: Bem apó és a székelyek, and Wikipedia/

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn