The Battle of Branyiszkó was a significant engagement with major consequences in the winter campaign of the 1848–49 War of Independence. On 5 February 1849, at the Branyiszkó Pass, the forces of Colonel Guyon Richárd, leading his Hungarian and Slovak troops, defeated the army of General Franz Deym, thereby forcing the breakthrough of the Transdanubian Army towards the main Hungarian forces concentrated at the Tisza River.

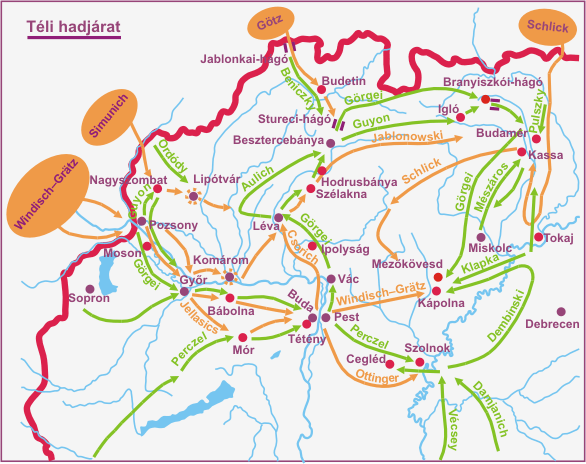

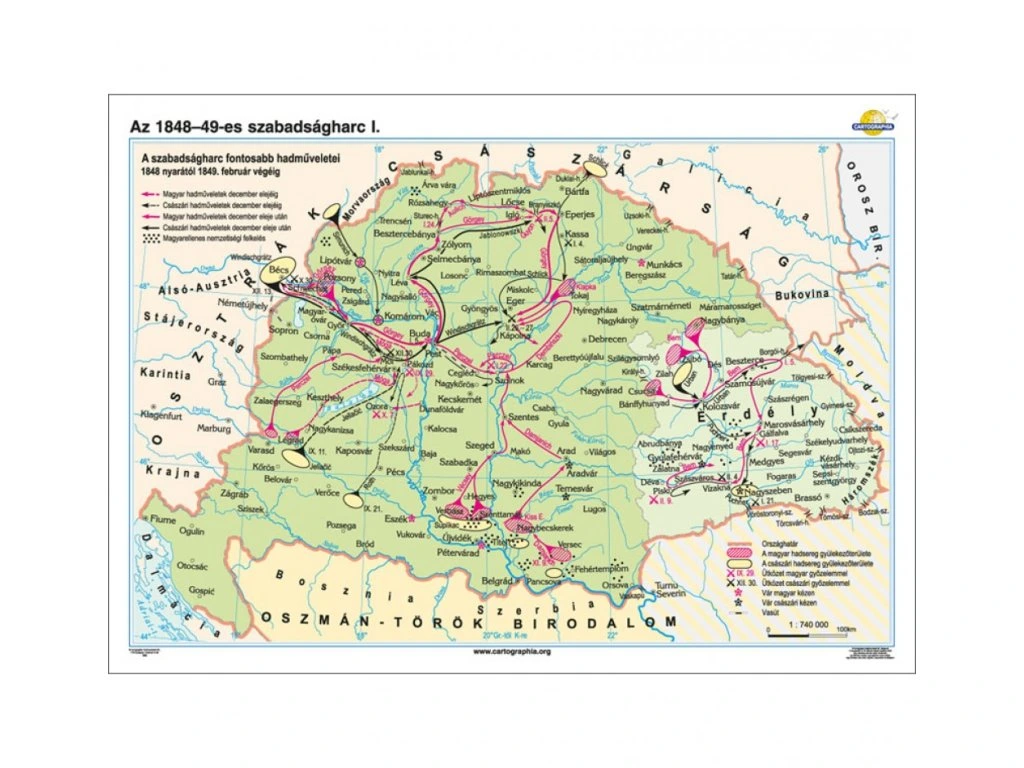

Following the surrender of the capital, the forces of Görgei Artúr set out toward Lipótvár in accordance with the military plan. However, as there were fears that he might be encircled by the Imperial troops positioned ahead of him and those pursuing him, he turned northward in mid-January toward the mining towns. Then, after several minor lost engagements, he proceeded through the Szepesség (Zipt, Spis) region of Northern Hungary.

As a result of Görgei Artúr’s campaign in Upper Hungary, Windisch-Grätz did not dare to move from Buda, because he had no precise information about the size and objectives of the split Hungarian army. The Görgei corps, which had turned northward, threatened the Imperial forces besieging Komárom fortress and Lipótvár with a rear attack, so the prince remained in Buda with his main force. He only sent individual pursuing units after Perczel and Görgei. Thus, the two weeks gained were enough for the Hungarian defense to solidify.

The corps set out toward the Szepesség region in two columns: one group, under the command of Görgei Artúr, proceeded through the Sturec Pass toward Poprád, while the other, led by Colonel Guyon Richárd, advanced in the direction of Igló. The vanguard of the corps approached Lipótvár to within forty kilometres, thus managing to temporarily break the siege encirclement. However, Görgei ultimately had to withdraw toward the mining towns. Here, Görgei—engaged in almost continuous rearguard actions and threatened by the forces of Götz from the north and Csorich from the south—received an order from Minister of War Mészáros Lázár to march toward Kassa in support of the operations against General Schlik.

Upon arriving at Lőcse, Görgei Artúr faced two possibilities. He could either approach Kassa (Kosice, Kaschau) by breaking through at Branyiszkó or advance against Kassa along the Hernád valley. Görgei chose the latter option. By taking the northern detour, he could cut off the route of Lieutenant General Franz Schlik, who was stationed near Kassa, to Galicia. Furthermore, he believed that a victorious battle would do his troops good. The Battle of Branyiszkó held significant stakes for both sides. The task of capturing the Branyiszkó Pass, which led to Eperjes (Presov) and Kassa, was entrusted to Colonel Guyon Richárd, a soldier of British birth with French and Irish ancestry.

Due to its natural features, the pass was exceptionally well-suited for defense. Its thirteen bends, the narrow sections of the road, and the steep terrain all favored the defenders, who sought to reinforce the pass—already serving as a natural fortification—with barricades. Guyon Richárd surveyed the pass and, in English, remarked only: “Devil take me if I do not pass through it.” Following this, he wrote his battle report in advance about the capture of the pass, leaving only the numbers of the dead and wounded blank.

Guyon Richárd’s division, after the losses suffered in the mining towns, consisted of the 13th and 33rd Battalions, a newly recruited Slovak battalion, a company of riflemen (vadászok), a company of sappers, a squadron of the Nádor Hussar Regiment, and 21 cannons. The total strength of the division was approximately four thousand men. Thus, the attackers possessed a more than twofold numerical superiority, but the terrain conditions favored the defenders.

The Imperial brigade led by Major General Franz Deym indeed had only about 1,800–2,000 men, roughly half the strength of the division attacking him under Guyon Richárd (approximately 4,000 troops). Deym’s forces, however, were battle-hardened units accustomed to success. In order to avoid being encircled, Deym sought to occupy the side roads, forest paths, and ravines adjacent to the pass. This occupation was not fully accomplished, but it had the unintended consequence of leaving Deym with scarcely any troops left to defend the pass itself.

With part of his forces, including the 33rd Battalion composed of men from Szeged, Guyon Richárd launched a frontal assault. Before the attack, he delivered a characteristic, mixed-language harangue to them: “Vorwärts dupla lénung, rückwärts kartács schiessen.” In English, this roughly translates to: “If you advance, you’ll get double pay; if you retreat, I’ll have you shot with canister.” After the initial assault failed, he indeed made good on his promise. Then, he himself took the lead and stood at the front of his soldiers.

Erdősi Imre, the Piarist monk, also came to his aid, encouraging the soldiers of the fresh battalion in Slovak. When the assault stalled nonetheless, Father Erdősi threw the one-meter-tall cross he was holding forward into the snow and said to the soldiers in Slovak: “Would you abandon God to these pagans?” This was always enough to make the valiant brethren turn back. Although Slovaks mostly fought on the side of the Habsburgs, roughly one-third of them battled on Kossuth Lajos’s side.

The life of Poleszni/Erdős Imre is a typical example of the 19th-century assimilation process in the Kingdom of Hungary. He came from a family whose roots were likely in a Slovak-speaking environment (or a mixed Slovak and Austrian one). However, through his education and career, he became integrated into Hungarian-language and cultural circles, and he became an advocate for them.

The success was also due in part to the Nádor Hussars, which were attached to the division. Their commander, Baron Emil Üchtritz, realizing that cavalry was useless for an uphill charge on the steep pass, left his hussars behind and, taking with him the division trumpeter and three companies of militia, set out up the mountain along a narrow side path. Meanwhile, he had the trumpeter sound a charge signal every ten minutes.

The defenders only heard troops approaching from somewhere on their flank as well. This, too, prompted Major General Franz Deym not to press the defense of the pass any further. All the more so because, on Guyon Richárd’s orders, part of the attacking forces had indeed begun moving up the mountainside, bypassing the roads, and Deym likely feared losing his entire force if he did not hasten his retreat. Meanwhile, the encircling troops appeared on the enemy’s flank, and Deym withdrew toward Eperjes. In the battle, the Hungarian forces suffered one hundred and fifty casualties, while the Imperial forces lost approximately eight hundred men.

The Feldunai (Upper-Danubian) Corps transformed from a defender into an attacker. By February 6, Görgei Artúr was already in Eperjes, and by the 10th, he had reached Kassa, which Franz Schlik had evacuated the day before. In recognition of the heroic conduct of the 33rd Battalion, it received from Görgei a gold-embroidered flag band inscribed with “Branyiszkó February 5, 1849.”

Consequences:

The Feldunai Army lost the overwhelming majority of the engagements in its Upper Hungary campaign; however, it essentially won the campaign because it tied down Windisch-Grätz’s forces for weeks, preventing a frontal assault on the Tisza River line, and ultimately—thanks to the breakthrough at Branyiszkó—emerged from the encirclement of Imperial troops without heavier losses.

The encirclement of the Schlik Corps ultimately failed—primarily due to the inaction of the high command, especially Henryk Dembiński. Nevertheless, the victory at Branyiszkó still had a significant impact on the further course of the war, as it enabled the unification of the Görgei Corps with the main Hungarian forces and, ultimately, the launch of the victorious Spring Campaign.

Legacy:

A few words must be said about the memorial plaque for Polesný (Erdősi) Imre in Selmecbánya (Banská Štiavnica, Schemnitz). It remained in its original location, in a public space, until the very end of the 1930s, after which it was taken down.

The removal of the plaque is closely linked to the erection of the Kmeť statue in the square. Upon the initiative of the Slovak League, the plaque with Hungarian text was deemed undesirable in the context of the statue erected in front of the former monastery building on June 19, 1938, and was initially covered up and later permanently removed in January 1938, before the statue’s unveiling, on the orders of the district office. In Selmecbánya, there was great outrage among both the Hungarian and Slovak populations. Further details were published in issue No. 2-3, 1938, of the periodical titled Kisebbségvédelem (“Minority Protection”):

“In relation to the memorial plaque of Erdősi Imre, the heroic priest of Branyiszkó, in Selmecbánya, the district office ordered the leadership of the Catholic Cultural House to remove the plaque within thirty days under penalty of a ten-thousand-korona fine or three months’ imprisonment, as it deeply offends Slovak national consciousness. As a continuation of this decision, they also intend to remove the Hungarian inscriptions on the seventeen Honvéd (soldiers) graves in Hodrus, as well as all Hungarian inscriptions in the Selmec museum.”

The memorial plaque remained in storage for a long time. After the fall of the communist regime, it was displayed for quite some time in the Óvár (Old Castle) of Selmecbánya, before eventually being returned to storage once again.

The erection of the Kmeť statue at one of the busiest points in the city was considered a major milestone in the symbolic Slovak appropriation of public space. Its significance was amplified by the fact that in Selmecbánya (despite its Slovak-majority population), relatively broad segments of society remained loyal to Hungary as late as 1938 (including a demonstration on September 28 demanding the city’s reattachment).

Kmeť, who was born in nearby Bzenica and studied at the Piarist gymnasium in Selmecbánya, was also a Catholic priest, famous not only for his scientific work but also as a cultural organizer (founding libraries, reading societies, fruit-growing and anti-alcohol associations). Due to his controversial figure (as a representative of the clergy, he was also known for anti-Semitic views), his statue was threatened with removal in the 1950s (plans were made to replace it with a statue of Stalin), but it ultimately remained in place.

Let us also mention the fate of the Honvéd Soldier statue erected in Lőcse (Levoča, Leutschau). It was the first public Freedom Fighter statue in Upper Hungary. Dedicated to the memory of the 1848–49 Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence, the golden cast-iron statue commemorated the Battle of Branyiszkó. The work of Faragó József, it originally stood in the main square of Lőcse, the centre of the Szepesség region, from 1875 until 1919. In that year, despite protests from the local population and as part of the wave of statue demolitions affecting historical Hungary, the Czechoslovak occupiers broke it into several pieces and removed it.

Sources: Hadtörténeti Múzeum, Orosz Örs, and Wikipedia

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn