Maria Theresa of Austria (1717-1780) is often remembered as the maternal heart of the Habsburg Empire, an enlightened reformer, and a formidable ruler who defended her birthright against a continent of adversaries. However, to view her reign solely through this lens is to ignore a more complex and, for the Hungarians, a more contentious reality. Behind the image of the caring “Mother of the Nation” was a determined absolutist monarch whose policies systematically undermined Hungarian autonomy, exploited its economy, and sowed the seeds of lasting national grievance.

The Pragmatic Sanction and the War of Broken Promises

The drama of Maria Theresa’s accession was rooted in deeper turmoil than it first appeared. Her father, Emperor Charles III, had already decreed the Pragmatic Sanction in 1723, which established the indivisibility of the Habsburg lands and legalized female succession—a measure recognized by numerous European powers in international treaties. Despite this, upon his death in 1740, a war immediately erupted over the Austrian succession. Frederick II of Prussia launched an attack on the Habsburg lands without a formal declaration of war.

A Queen in Peril and the Hungarian Lifeline

The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) that followed led to the empire losing the rich province of Silesia, which Prussia annexed. In this war against Austria, Prussia was joined by France, Bavaria, and Saxony. From the outset, Austria was severely disadvantaged. The country had only just concluded a war against the Ottoman Empire the previous year.

Furthermore, Maria Theresa’s own father, the aging Emperor Charles III, had allowed Austria to be recklessly drawn into a conflict with Russia, which was also at war with the Ottomans. This misadventure resulted in the loss of vast Serbian, Bosnian, and Wallachian territories that Austria had acquired in the 1718 Treaty of Passarowitz, leaving the treasury depleted and the military overstretched.

A Queen in Peril and the Hungarian Lifeline

It was in this moment of profound crisis—betrayed by European powers, attacked on multiple fronts, and inheriting a weakened state—that the young and inexperienced queen turned to the one kingdom whose support was crucial yet uncertain: Hungary.

Maria Theresa was well aware that she could only defend her throne from the Prussian threat with the help of the Hungarian estates, and she also knew that the organization of the empire needed modernization. To win the support of the Hungarians, she presented her requests at the convened Diet of Pressburg.

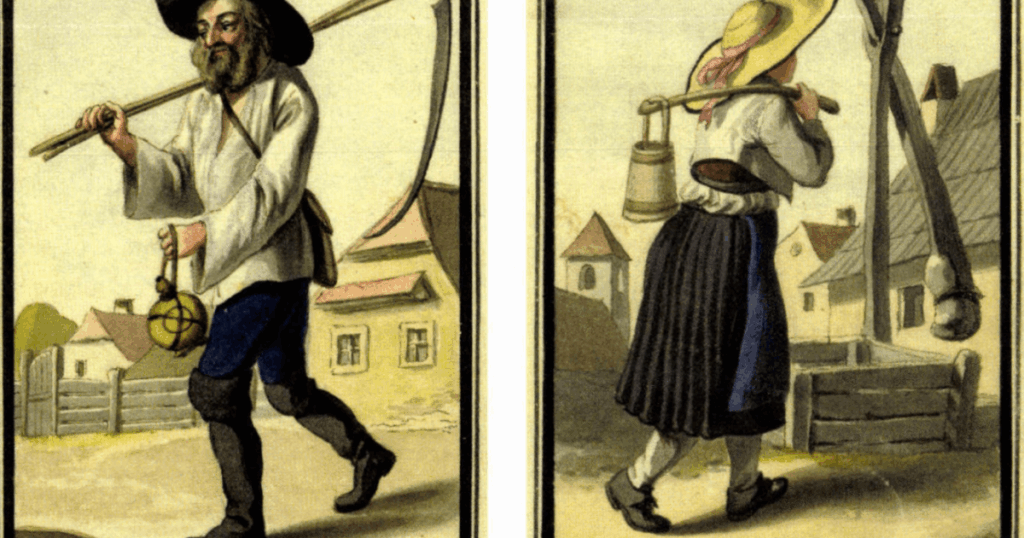

The Hungarian estates initially showed resistance. The monarch appeared personally at the diet, wearing mourning clothes and holding her son, the infant Joseph II, in her arms. This later became known as the famous “Scene of Pressburg.” The young queen delivered an effective speech, after which, it is said, the attending Hungarian nobles unanimously declared: “Vitam et sanguinem pro rege nostro!” (“Our lives and blood for our king!”).

With this public acclamation, they stood by their king, who, in return, invalidated some of King Charles III’s anti-Hungarian measures, legally confirmed the tax exemption of noble estates, and permitted the use of the Hungarian language for military commands. In exchange for these royal concessions, 11 Hungarian hussar regiments (about 35,000 soldiers) fought for the Habsburg throne on the battlefields of Europe during the War of the Austrian Succession.

Without the swift mobilization of the Hungarian nobility and their formidable military levies, the Habsburg monarchy would almost certainly have perished. The Hungarian hussars and infantry became the backbone of her resurgent armies, playing a decisive role in defending her throne. This critical context is essential: Maria Theresa’s entire reign, and the very survival of the Habsburg line, was built upon a debt of gratitude owed to the Hungarian nation.

The Betrayal: Centralization and the Erosion of Liberty

Once the immediate threat had passed and her power was consolidated, the queen’s gratitude proved to be conditional. The Hungarian elite had expected a partnership, a renewal of their ancient rights in exchange for their loyalty. Instead, they found themselves facing a relentless campaign of administrative and economic centralization designed to bind Hungary more tightly to Vienna.

She tried to limit the power of the estates. Among her most important reforms was the separation of executive power from the judiciary, meaning that those responsible for executing the laws and decrees were no longer the same people overseeing their implementation. In 1761, on the recommendation of Chancellor Kaunitz, she established a State Council, which provided significant professional support for political decision-making. At the same time, she abolished the secret court councils that had been operating since the 16th century.

The most blatant instrument of this policy was the “Institutum Dominorum Nostorum” (Institution of Our Lords), established in 1765. This was a parallel government, a body of royal commissioners—often non-Hungarians—appointed by and answerable only to the crown. It effectively bypassed the traditional Hungarian county administration and the Diet, rendering Hungary’s constitutional institutions secondary. From the critical Hungarian perspective, this was a naked power grab, a direct violation of their constitution, and a fundamental breach of the trust forged in 1741.

According to mainstream historiography, her later enlightened absolutist decrees also had a significant impact on Hungary. These included the dual tariff system introduced in 1754, the 1777 Ratio Educationis, the reform and relocation of the University of Nagyszombat to Buda, and the annexation of Fiume to Hungary.

Regarding the dual tariff system, the impact was not positive at all. Economically, Hungary was treated as an Imperial resource to be exploited. The wealth from its vast agricultural lands, the “contributio” tax, and other revenues were systematically funneled westward to finance the development of the Austrian hereditary lands and the upkeep of the Imperial court in Vienna. Deliberate policies hindered Hungarian industry from preventing competition with Austrian manufacturers, ensuring the kingdom remained a semi-colonial supplier of raw materials and a captive market. The queen’s tariff decree provoked serious resistance.

To make it clearer: a separate customs border was established between Hungary and the hereditary provinces, with very high duties imposed on manufactured goods exported from our country. Similarly, high tariffs had to be paid when raw materials or agricultural products were to be exported outside the empire. In contrast, duties were low on manufactured goods arriving in Hungary from the hereditary provinces, and on Hungarian agricultural goods if they were sent to the hereditary provinces.

Maria Theresa promised that under her rule, every peasant family would have a chicken boiling in the pot once a week. It should be noted that, unlike in Western countries, the common people in Hungary during this period still had abundant access to meat.

Due to the immense burdens on the serfs, several serf uprisings (for example, in Transdanubia between 1765 and 1766) broke out during the time of Maria Theresa. After the Hungarian feudal diet refused to address the serf issue, the queen regulated this matter by decree. This decree, issued in 1767, was called the Urbarium or Urbarial Patent.

In it, the ruling queen sought to protect the serfs from the landlords and to safeguard their ability to pay taxes. It regulated the serfs’ burdens, rights, and the size of their plots. Every serf owning a full plot was required to provide their landlord with one day of robot with draught animals or two days of manual robot (corvée) per week. The monetary tax was set at 1 forint, irrespective of the size of the plot. In addition to the robot, a ninth of the harvest—the so-called kilenced (a tithe)—had to be delivered from grain, wine, flax, hemp, as well as from beehives and lambs.

Furthermore, certain manorial privileges were ceded to the serfs for one or two days per year, and the boundaries of the plots were fixed. While the Urbarium decree alleviated the situation for serfs in the western regions, it made subsistence more difficult in other areas, such as the Great Plain.

In keeping with the spirit of the age, her 1777 education decree, the Ratio Educationis, placed the entire education system in Hungary under state control and regulated it uniformly. Contrary to popular belief, it did not introduce universal compulsory education. By creating the gymnasium (academic secondary school), it connected elementary and higher education, established teacher training colleges, expanded university faculties, and founded new ones.

She also supported healthcare. She decreed that care must be provided for the poor, the sick, the elderly, and orphans. This was not, of course, something that other rulers had not been doing for centuries.

The Decree Against the Roma (Gypsies):

The Regulatio Cigarorum decree is associated with the name of Maria Theresa. This marked the beginning of the forced integration and assimilation of the Roma people. In her decree of November 13, 1761, she prohibited the further use of the name “Gypsy” and made their new designation mandatory: “new settlers,” “new Hungarians,” or “new peasants” (in German: Neubauer). With her decree issued on November 27, 1767, Maria Theresa forbade marriage among the Roma. She ordered a census of the “new peasants” to be taken every six months and prohibited and punished the eating of carrion.

Was she really a friend of the Hungarians?

During the reign of Maria Theresa, the marginalization of the Hungarian estates continued. Like her predecessors, Maria Theresa continued the policy of settling people in Hungary. At the expense of the state treasury, tens of thousands of German-speaking settlers were brought from the western provinces of the Empire and settled in the areas around Pest, Vecsés, Buda, and Esztergom, in the Pilis mountains, in Szatmár County (in place of the Hungarian population decimated during Rákóczi’s War of Independence), in Baranya, in the Southern Region (Vojvodina), and in the Banat (in these last three locations, replacing the Hungarian population that had been wiped out during the Ottoman period).

Although the Bánát Region was part of the Hungarian Crown, it was administered by an Imperial commissioner, and the return of the Hungarian population was prohibited there until 1778.

During Maria Theresa’s reign, 350,000 to 400,000 Romanians immigrated into the territory of Hungary, the Banat, and Transylvania from beyond the Carpathians. This Romanian immigration from beyond the Carpathians, coupled with significant Hungarian emigration primarily to the eastern edges of the Great Plain, substantially altered the ethnic ratios of the Transylvanian population.

From 1765 until the end of her reign, she governed using enlightened absolutist methods and did not convene a diet during this time.

The military reforms

The military organization also required reforms. The older system of recruiting mercenaries for each war was replaced by a standing army. They also abandoned the practice of stationing military units in scattered towns and villages, which were responsible for their own supply. Henceforth, individual units were maintained in larger formations, typically by the regiment, and the state authority provided for their supply centrally.

Until then, each regiment had its own regulations, based on which it trained and fought; even their uniforms were not standardized. These aspects were also regulated as a result of the reforms. Later, as we will see, the forced recruitment would have bloody consequences in Transylvania.

The queen had a particular fondness for the handsome Hungarian hussars. On September 11, 1760, she established the “Hungarian Royal Noble Bodyguard.” The 1764 diet offered an annual 100,000 forints for the unit of 100 young nobles and regulated that the candidates were to be recommended by the counties themselves. Furthermore, Transylvania separately provided 20,000 forints for the maintenance of twenty bodyguards. The entire guard consisted of 120 men; its captain was always a member of the army’s general staff, and according to Article VI of 1765, they were enrolled among the flag-bearers of Hungary.

The role of this bodyguard diminished during the reign of Joseph II, but being a member remained a great honor until 1848. The elite unit also included the famous “Bodyguard Writers,” who laid the foundations of modern Hungarian literature: Bessenyei György, Orczy Lőrinc, Gvadányi József, Dugonics András, and Pálóczi Horváth Ádám.

The Blood of Mádéfalva: The Ultimate Repression

No event better encapsulates the iron fist within Maria Theresa’s velvet glove than the Tragedy of Mádéfalva (Siculicidium) in 1764. To bolster the military border against the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburgs had long maintained the Székely people, a Hungarian-speaking community in Transylvania, as a privileged military class. When Maria Theresa’s government sought to forcibly conscript them into new, regular army regiments—a move that would have eroded their ancient autonomy and reduced them to common serfs—the Székelys resisted.

The Imperial response was swift and brutal. On January 7, 1764, Imperial troops descended upon the village of Mádéfalva, where many Székelys had gathered. They opened fire on the largely unarmed crowd, massacring hundreds of men, women, and children. In the massacre, approximately 400 people, including women and children, lost their lives. This event triggered the mass migration of the Székely people to Moldavia and Bukovina.

The bloodshed at Mádéfalva sent a shockwave through the entire kingdom. It was a stark message: Hungarian liberties, even those of a historic frontier guard, were expendable when they conflicted with the crown’s centralizing and military ambitions. The memory of this massacre became a powerful symbol of Habsburg oppression and a rallying cry for Hungarian patriots for generations to come.

Conclusion: A Complex and Contested Legacy

Maria Theresa was undoubtedly one of the most significant rulers of the 18th century. She was a capable administrator, a social reformer, and a matriarch who held her diverse empire together. Yet, her legacy in Hungary is profoundly dualistic.

She is the queen who, in a moment of existential crisis, was saved by the very people she would later subjugate. The narrative that criticizes her reign points to a fundamental hypocrisy: the reliance on Hungarian “life and blood” for survival, followed by the systematic dismantling of Hungarian autonomy through institutions like the Institutum, economic exploitation, and, in the case of the Székelys at Mádéfalva, brutal military repression.

The reason for her persistently positive portrayal in mainstream historiography is rooted in this very duality; to this day, Hungarian memory remains divided between the “labanc” (pro-Habsburg) perspective that emphasizes stability and her reforms, and the “kuruc” (anti-Habsburg) viewpoint that focuses on national resistance and the loss of liberty.

To understand Maria Theresa fully, one must look beyond the enlightened empress of Vienna and see also the ruler who, once secure on the throne her Hungarian subjects had saved, proved that the interests of the Habsburg dynasty would always supersede the freedoms of the Hungarian nation. The velvet glove of maternal care could not fully conceal the iron will of an absolutist sovereign.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn