The Cumans are a distinctive patch of color on the ethnic map of Hungary. Writings about them highlight their warrior nature and the untamed spirit born of a nomadic way of life, traces of which can still be found in the unique historical consciousness of the Cuman people today.

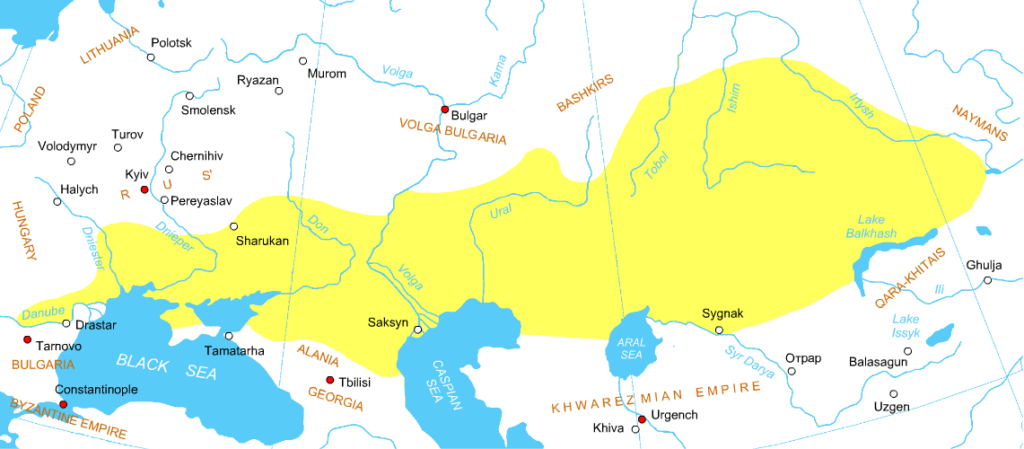

The Cumans originally led a nomadic, large-animal herding lifestyle, living in tribal-clan organizations and tent camps. They established the most powerful nomadic state in 11th-12th century Europe, located in what is now Kazakhstan and later Ukraine. Contemporary chronicles and reports referred to this state as Cumania. Their craftsmanship in metalworking and metal processing was likely highly advanced. They spent most of their time herding and raising livestock. According to material and linguistic evidence, some groups, when they settled in one place for a longer period, also engaged in agriculture.

In the wake of the cataclysmic Mongol invasion of 1241-42, which decimated Hungary’s population, King Béla IV faced a stark imperative: to rebuild and defend a shattered kingdom. His visionary, if perilous, solution lay not in the West, but in the East. He extended an invitation to the very steppe warriors whose kin had ridden with the Mongol vanguards—the nomadic Cuman (Kuman, Kun) and Jász peoples. This decision initiated one of medieval Europe’s most ambitious experiments in statecraft: the deliberate, charter-based integration of large, non-Christian, nomadic populations into the heart of a Christian realm.

The story of the Cumans and Jász is the definitive test case of the Hungarian model, demonstrating how royal charters could transform feared outsiders into a cornerstone of the kingdom’s frontier defense, all while navigating profound cultural and religious divides.

The Newcomers: A Strategic Alliance Forged in Crisis

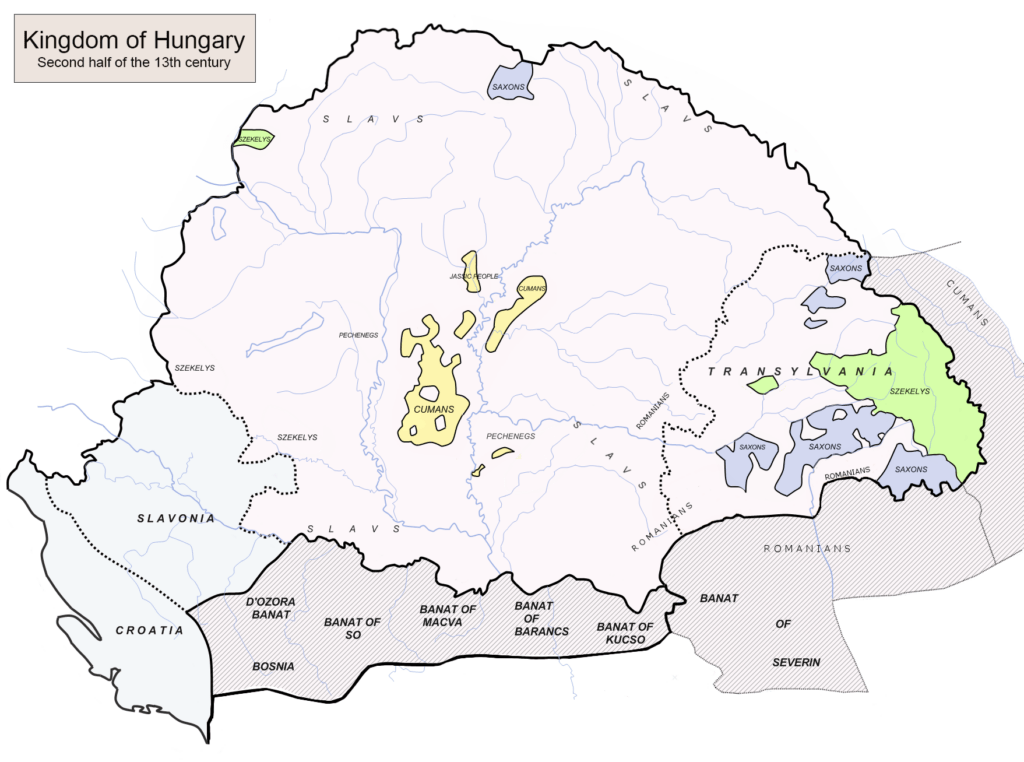

The two peoples, though often grouped, possessed distinct origins. The Cumans (known in Europe as Kipchaks or Kuns) were a Turkic confederation from the Pontic-Caspian steppe. While smaller other Turkic groups (such as Pechenegs/Besenyő or the Oghuz) were settled in the country during the 11th century (1070/1091), the definitive Cuman (Kipchak) migration to Hungary was a direct result of the Mongol expansion in the 13th century.

The pivotal event was the arrival of Khan Kötöny and his 40,000 followers in 1239, seeking refuge and forming an alliance with King Béla IV. The king, needing a potent military force to counter both internal dissent and the inevitable Mongol attack, formalized a strategic alliance. The Cumans pledged loyalty and future conversion to Catholicism, a bond sealed by the marriage of Kötöny’s daughter, Elizabeth, to the king’s son, Prince István.

Sadly, the alliance was shattered at the onset of the Mongol invasion in 1241. Consumed by suspicion that the Cumans would betray them, Hungarian nobles—led by Austrian Ladislaus and the royal guard—assassinated Khan Kötöny and his retinue, likely with King Béla IV’s tacit consent.

This preemptive strike triggered a catastrophic reversal: the enraged Cumans ravaged the Hungarian countryside as they fled, critically weakening the kingdom’s defense and directly contributing to the ensuing Mongol victory. This rupture revealed the fatal limits of an informal pact, setting the stage for a more structured, charter-based relationship upon their return after 1246. This migration established the Cuman presence as a major political and military force within the kingdom

In contrast, the Jász were an Indo-European people of Alanic origin from the Caucasus, relatives of the modern Ossetians. They arrived in the same turbulent period, seeking refuge as well. While sharing the Cumans’ elite equestrian culture, their distinct ethnic and linguistic background set them apart.

King Béla’s strategy for both groups was clear: settle them in the devastated but strategically vital Great Plain, where they could repopulate the land and form a permanent, dedicated light cavalry force. Their core service, as pristaldi (frontier guards), was to provide agile armed horsemen for the royal army—a military niche they alone could fill.

For 150 years, the Cumans became the mainstay of the Árpád dynasty kings. For the Árpád kings, the Cuman community was of great military importance, as the Hungarian king lacked a sufficiently large, immediately mobilizable, and loyal army. Thus, alongside the Székelys, the Cumans became the most important Hungarian ethnic element on Hungarian soil—one without whom no Hungarian king would henceforth go to war. During the Árpád era, the Hungarian Kingdom’s army reached a maximum strength of 40,000–50,000 men, of whom 10,000 were Cuman soldiers.

The Charter Framework: Codifying Autonomy and Service

The relationship was not sustained by mere goodwill but by a sophisticated legal framework of royal charters. These documents translated a military alliance into a durable socio-political structure.

For the Cumans, their autonomy was powerfully confirmed by King Ladislaus IV (the Cuman) in 1279. This charter formally settled them in the defined territories of Nagykunság and Kiskunság, and the interfluves of the Tisza, Maros, and Körös rivers. It guaranteed their self-government under their own leaders, obligations limited to specific military service, and exemption from all other taxes and feudal levies.

During his reign, the Cumans achieved considerable influence. They were at that time the support of the Hungarian king in the confrontation with the rebellious nobles. Their military utility was demonstrated on a European stage in 1278, when László dispatched a formidable contingent of Cuman horse archers to aid the German King Rudolf I of Habsburg at the Battle on the Marchfeld.

Their swift, mobile tactics were instrumental in defeating the Bohemian King Ottokar II, a victory that decisively secured the Austrian duchies for the House of Habsburg. Thus, the Cuman warriors, settled and secured by Hungarian charters, became unwitting architects of a dynastic fortune that would later come to dominate their own homeland. However, it was his trusted Cumans who finally assassinated King László IV.

The Jász received similar extensive privileges, administered through a royal comes (count) often drawn from their own ranks. Their unique Alanic legal traditions were codified and preserved in the Jász Book (Jász Könyv), a testament to the crown’s respect for their distinct customary law. The charters for both peoples created autonomous enclaves—Kunság and Jászság—where they could live under their own laws, sustain their social structures, and fulfill their military duty as a collective privilege.

Conflict and Coexistence: The Perilous Path to Integration

The path was never smooth. The Cumans’ prominence, especially under their half-Cuman king, László IV, provoked intense backlash. The Church agitated for their forced conversion, and magnates resented their royal favor and privileges. This culminated in the persecution of the 1280s, their removal from court, and a decisive military defeat by Hungarian barons at the Battle of Lake Hód in 1282.

For the Jász, integration appears to have been less politically tumultuous but followed a similar legal and cultural course. The earliest mention of the Jász people in Hungary, whose name appeared as Jasso, goes back to the year 1245. In 1318, they were mentioned as Jazonicus in the register of the Chapter of Gyulafehérvár. In the charter of privilege of King Károly I in 1323, they are mentioned as Jasones.

During the 14th century, parallel to the Cumans’ transition to a settled lifestyle and their conversion to Christianity, they evolved into territorial administrative units known as Cuman “széks” (seats). These seats were led by captains. A total of six such seats are known to have existed. They set their own laws and were accountable directly to the palatine. This unique legal status, unparalleled in Europe, lasted until the 19th century.

Autonomy was not revoked but renegotiated and reaffirmed, as seen when King Ulászló II reconfirmed Jász privileges in 1501. Over the following centuries, a gradual, deep assimilation occurred. Both peoples converted to Christianity, adopted the Hungarian language, and their settlements became indistinguishable from those of their neighbors. Yet, crucially, this was not a simple ethnic dissolution. They retained a distinct legal and corporate identity as the nationes Jazygum et Cumanorum—the Jász and Cuman nations—within the Hungarian body politic. Their assimilation was administrative and cultural, but their historic status, rooted in the 13th-century charters, endured.

The final destruction came from a tragic irony: another Turkic people, the Ottoman Turks, who devastated their homeland in the 16th-17th centuries. Even then, a 16th-century Ottoman traveler noted some Cumans still lived in yurts and spoke their dialect—a last glimpse of their steppe world before assimilation was complete.

A Lasting Steppe Legacy in the Heart of Europe

Their unique status was constitutionally defined. The territories of Kunság and Jászság were Crown lands, exempt from landlord jurisdiction. Their ultimate protector was the Palatine of Hungary, who legally defended their privileges and self-governance. This framework, formalized in charters like that of László IV in 1279, allowed them to preserve their laws and social structures for centuries.

The integration of the Cumans and Jász stands as a landmark achievement of pragmatic medieval statecraft. The Hungarian Crown, through the deliberate use of royal charters, successfully harnessed the military prowess of steppe societies for the kingdom’s defense. The system absorbed severe political shocks and facilitated a centuries-long transition from nomadic outsiders to settled defenders, all while allowing for the preservation of an honourable, distinct identity. The Cuman people integrated into the Hungarian nation in such a way that while they exchanged their language, they have preserved their identity to this day.

The life of the “Jász-Kuns” after the Ottoman rule

From 1696, the independent administrative and judicial rights of the Jászkun, which had existed from the beginning, were extended by the introduction of an independent taxation similar to that of the Cumans, thus creating the conditions for the political unity of the Jászkun district; a jurisdiction was established. Did the Habsburg rulers handle the situation in the same manner?

The integration of the Cumans and Jász stands as a landmark achievement of the pragmatic medieval statecraft of the Hungarian kings. Their charter-based autonomy, however, would face its final test not from steppe invaders but from the crown that had once granted it. And then, that crown was in Habsburg hands.

In 1702, needing funds for the War of the Spanish Succession, Emperor Leopold I treated their lands as a mere asset, selling the privileged districts of Jászság and Kunság to the Teutonic Knights for 500,000 gold florins.

This act provoked immediate outrage, challenging the fundamental principle that Crown lands were inalienable without the Diet’s consent—a right even the royalist Palatine defended. Consequently, when Prince Rákóczi Ferenc II rebelled against Habsburg rule, he swiftly voided the sale.

Conclusion: Redemptio – The Charter Reclaimed

The story of the Cumans and Jász reaches its most profound chapter in the modern era. The 1702 sale of their lands was not the end, but a catalyst. Following the 1711 Peace of Szatmár, which promised redress, the Jász and Cumans—now collectively the Jászkuns—launched a decades-long political and financial campaign to reclaim their autonomy. In a supreme act of collective agency, they proposed the redemptio: to buy back their own freedom.

The struggle culminated under Empress Maria Theresa. During the War of the Austrian Succession in 1744, their leaders, bridging religious divides, petitioned for restoration. Their offer was stark: a massive payment of 575,900 gold florins and the provision of a dedicated Jászkun Hussar regiment. On 6 May 1745, Maria Theresa signed the Charter of Redemption.

This was more than a transaction; it was a societal transformation. The redemptus—the free, propertied citizen of Jászkunság—was born, liberated from all manorial dependency. Redemptio forged a unique, prosperous peasant society with extensive freedoms, which became a model for later serf emancipation. It happened at this time that Varró István, the last known speaker of Cuman, dictated the Cuman Lord’s Prayer to a scholar in Vienna, preserving a final echo of their ancient tongue even as they fought for their future.

In defending this hard-won status, the Jászkuns maintained a legendary military tradition for generations. This ethos, however, was ultimately in service to their homeland and freedoms, not uncritical loyalty to a dynasty. Their famed hussars fought with distinction in the Napoleonic Wars and, most tellingly, in the 1848-49 War of Independence against the Habsburg crown, symbolizing their ultimate allegiance to Hungarian constitutional liberty and their own ancient covenant of autonomy.

The Jászság region was, until 1876, a part of the Jászkun district as an administrative unit not under the county authority. Their legacy is etched into Hungary’s map in the regions of Kunság and Jászság, which retained their formal autonomy until the modernizing reform of 1876. Jászkun military valour was a legendary concept until the end of the Second World War.

If we simply list our words of Cuman origin, we can observe how they blended into the Hungarian language just as the Cumans themselves blended into the Hungarian people. Such words of Cuman origin, which have become an integral part of the Hungarian language, include: balta (axe), bicska (knife), buzogány (mace), csákány (pickaxe), hurok (loop, snare), kalauz (guide, conductor), kobak (head, noggin), komondor (Komondor dog), köldök (navel), köpönyeg (cloak), özön (torrent, flood), tőzeg (peat).

More than a historical footnote, the story of the Cumans and Jász provides a powerful blueprint for how pre-modern states could, through legal innovation and strategic compromise, turn the challenge of foreign coexistence into a source of enduring strength.

Thus, the legacy of the 13th-century charters proved alive. It fueled a legal battle, shaped a social ideal, and defined an identity so potent that it motivated a people to ransom themselves back into liberty—a final, definitive testament to the enduring power of the Hungarian model of charter and coexistence.

Their present

The settlements of Kiskun and Nagykun launched a triennial event series called the Cuman World Gathering with the aim of nurturing Cuman traditions, preserving Cuman identity, and fostering its further development. The first such world gathering was organized in 2009.

In June 2006, two stone statues by sculptor Győrfi Sándor, donated by Gubcsi Lajos, were unveiled at the Ópusztaszer National Historical Memorial Park, commemorating the shared past of the Cumans and Hungarians. The soil needed for the construction of Kun Halom (Cuman Pile) was brought to Ópusztaszer by settlements in Kiskun and Nagykun as a symbol—and a fine example—of unity. Each settlement donated 4 cubic meters of its own soil, enabling the construction of the nearly 3-meter-high, 14-meter-wide mound.

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn