For many Slovaks, the name Felvidék is a provocative insult, just as the name Slovakia is for Hungarians. For Slovaks, “Felvidék” is often seen as a denial of Slovak statehood and a symbol of Hungarian revisionism. For some Hungarians, “Slovakia” may represent the loss of historical territory. The motivations differ—one is about identity preservation, the other about territorial memory.

It is time to learn about its history. First of all, it should be noted that there are several similar geographical names in (historical) Hungary, such as Balaton-felvidék, Sóvidék, Délvidék, Őrvidék, Drávavidék, Tiszavidék, Erdővidék, etc., but none of them cause such strong emotions. Now, in the Slovak public consciousness, the concept of Felvidék is often associated with the perceived threat of Magyarization and the restoration of historical Hungary.

The term Felvidék (Horná Zem in Slovak, meaning Upper Land) is a concept that has changed over time and currently refers primarily to the territory of present-day Slovakia. Literally, it means “Upper Country” in Hungarian. It is not a uniformly homogeneous region, and its historical development was identical to that of the Kingdom of Hungary until 1918, after which it evolved as part of Czechoslovakia and later became part of Slovakia.

This region included the areas north of the Pozsony-Nyitra line in what is now western Slovakia. To the east, however, it also included parts of present-day northern Hungary (the areas around Miskolc and Salgótarján) and the mountainous part of present-day Carpathian Ruthenia, and even included the area of Máramaros. Read more about Máramaros: https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/maramaros-region-in-transylvania/

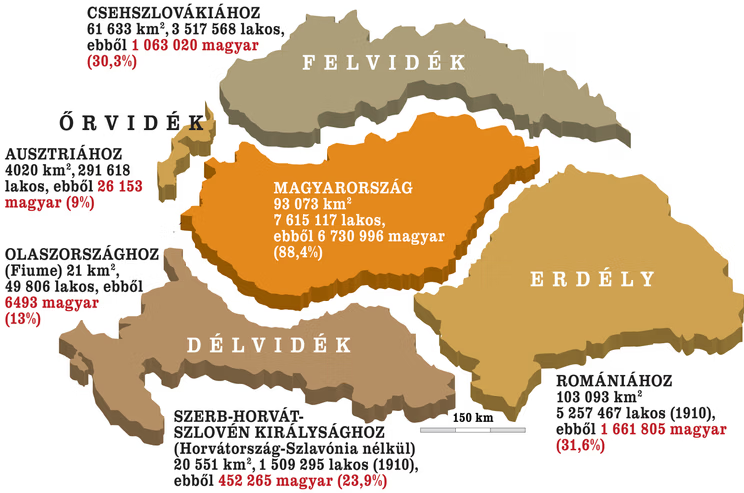

Today, the majority of the population in the region is Slovak, but there are also significant minorities of other nationalities (e.g., Hungarian, German, Ruthenian, and Roma) and religious minorities. The Hungarian population in the region, including Subcarpathia, has been halved over the past century, from roughly one million to about five hundred thousand. This stark reduction is not a natural demographic shift but the direct result of historical tragedies: forced assimilation, the mass deportations of the Beneš decrees, and other disruptive state policies.

Felvidék is a place name of historical origin that has had several meanings in the past. Today, as we have said, it is used as a synonym for the territory of Slovakia – on the one hand, in relation to the Hungarians living in Slovakia (“Felvidéki Hungarians”), and on the other hand, in connection with Hungarian history before 1918, when the territory of present-day Slovakia was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary, often referred to as Felföld or Felső Magyarország.

The term Felföld (Highlands) became widespread in the 16th century as the conceptual opposite of Alföld (Great Plain), which refers to flat terrain. Its use began to be replaced in the 19th century by the term Felvidék, which was initially used in a more spiritual and cultural-geographical sense, but gradually took on the meaning of the term Felföld, referring to the higher, mountainous areas of northern Hungary. According to ethnographer Liszka József, the first mention of the word “Felvidék” comes specifically from Kossuth Lajos in 1848.

Thus, it included not only the Tatra and Fatra mountain ranges, but also the Zemplén, Bükk, Mátra, Cserhát, and Börzsöny regions. However, the Csallóköz plain was not considered part of the Felvidék region.

The situation became even more complicated with the creation of Czechoslovakia in 1918. At that time, Hungarian public opinion clearly regarded the Felvidék as the northern territories that had been separated from Hungary.

In 1938, when the Hungarian-majority areas of southern Slovakia were returned to Hungary, the Hungarian press wrote about “the return of the Felvidék,” which further reinforced the political connotation of the term.

Today, the meaning of “Felvidék” is limited to the territory of Slovakia. The area is commonly referred to by this name in Hungarian historical, geographical, and cultural contexts, both in relation to Hungarian history before 1918 and in relation to Hungarians living in Slovakia (“Felvidék Hungarians”). Thus, Felvidék and Slovakia can be considered synonyms, and which one we use depends on the topic. Recently, however, Hungarians in Slovakia have come to understand “Felvidék” to mean the Hungarian-speaking area of Slovakia.

It is also worth noting that this name is politically charged, its meaning has constantly changed, and today it does not refer to a definable geographical area, but rather to an identity. Let me cite here from the article of Halász Béla:

“For many Slovaks, the words ‘Felvidék’ and ‘autonomy’ are not painful in themselves, but because they touch on historical fears and ingrained attitudes that Slovak society has not yet been able to truly confront. These terms do not exist in the public consciousness as legal or administrative concepts, but as emotionally charged symbols that are immediately associated with suspicion, danger, and ill will. The root of the problem lies not in the words themselves, but in the meaning that has been attached to them for decades.

“Felvidék” is a traditional geographical and historical term in Hungarian historical and cultural thinking. It does not imply a denial of present-day Slovakia, nor does it express a territorial claim, but rather refers to a region that was an integral part of the Kingdom of Hungary for centuries. In Slovak public discourse, however, the term Felvidék often appears as if it were questioning the legitimacy of Slovak statehood. This interpretation does not stem from the actual meaning of the word, but from a defensive nation-building logic that treats any historical reference as a potential threat. However, just as the names Szepesség, Gömör, or Csallóköz do not threaten Slovakia’s territorial integrity, neither does the word Felvidék.

This distorted view of history is particularly evident in the consistent use of the word Uhorsko, which is used almost exclusively in Slovak and Czech historical language. Uhorsko is nothing more than the Slavic name for the Kingdom of Hungary, yet in everyday speech and often in textbooks, it appears as if it were a “different” state, not Hungarian. It is as if the Kingdom of Hungary and Uhorsko were two separate historical entities, even though this is historically untenable. In medieval and early modern Europe, the Kingdom of Hungary existed as a unified state in legal, political, and international terms, with the Hungarian people as its constituent nation, regardless of the fact that several languages and ethnic groups lived within its territory.

The use of the term Uhorsko in this way is not a linguistic issue, but a political one. It serves to relativize the historical continuity of Hungarian statehood and to create the impression that Slovaks did not live for centuries as part of a historical Hungarian state, but under a kind of oppressive, foreign entity. This narrative is convenient because it allows for the simplification of the past, the shifting of responsibility, and the “extension” of the history of the modern Slovak nation-state back to the Middle Ages. However, this does not make it any truer.

The same logic applies to the rejection of the word autonomy. In Western Europe, autonomy is a means of stability and loyalty, but in Slovakia, many automatically equate it with secession. This is not based on any real political threat, but rather on historical trauma and mistrust. A young state often overprotects itself and interprets any extension of minority rights as a threat. However, this is not a sign of strength, but of insecurity.

All this is further reinforced by political manipulation. The narratives built around Felvidék, autonomy, and Uhorsko are excellent for instilling fear, creating enemy stereotypes, and diverting attention from the real problems: the economic backwardness of the regions, the depopulation of the southern regions, and the state of education and healthcare. When the arguments run out, the “Hungarian threat” is brought up again and again, because it always offers emotions that can be mobilized.

The reality, however, is much simpler and more sober. The Hungarian community in Felvidék does not want to change borders, but rather desires dignity, legal certainty, and predictability. It does not want to live in another state, but rather in the one in which it lives today, while preserving its language, culture, and identity. Autonomy is not secession, Felvidék is not a threat, and Uhorsko was not a lost, mysterious state, but the name of the Kingdom of Hungary in another language.

The problem, therefore, lies not in the words themselves, but in the fact that fear is still being taught about them instead of understanding and honest dialogue. And as long as this remains the case, it is not the past, but the misinterpretation of the past that will continue to burden the present.”

Sources: Halász Béla, https://www.korkep.sk/cikkek/szemle/halasz-bela-miert-es-mitol-felnek-a-szlovakok/

Török Máté, Szlovákiai Magyar Adatbank https://adatbank.sk/lexikon/felvidek-2/

Recommended source: https://www.hunsor.se/hu/felvidek/felvidektortenete.htm

About the Benes Decrees (in English): https://www.hungarianottomanwars.com/the-benes-decrees-and-my-grandfather/

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all

Subscribe to my newsletter here: https://tinyurl.com/4jdjbfkn