The Treaty of Várkony: the legend of the crown and the sword

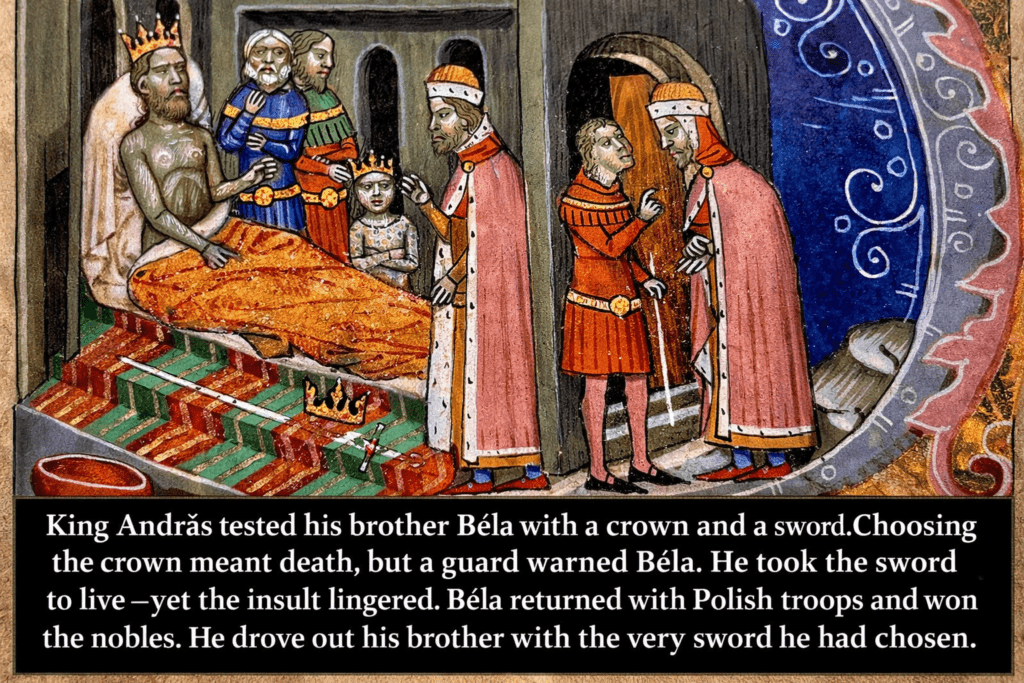

“I wish to put the duke to the test and ask him whether he desires to hold the crown or the duchy. If he wants the duchy in good peace, so be it, but if he wants the crown, the two of you, noblemen, rise at once and take his head with that sword.” – According to the description in the Chronicon Pictum, this was the instruction given by King András I (1046–1060) to two of his confidants before receiving his brother, Duke Béla (Béla I, 1060–1063), at the end of 1059 in Várkony fortress. Although the history of the Árpád dynasty is replete with family dramas, the tragedy of the brothers is particularly noteworthy because, in the story of the crown and the sword, imbued with legendary elements, every factor that influenced the existence and determined the future of the early Hungarian state is evident.

The exiled princes—András, Béla, and Levente—were able to return to their homeland nearly a decade and a half after they had been forced to flee due to the failed conspiracy of their father, Vazul, against King Saint Stephen (1001–1038). Béla settled in Poland, while András and Levente settled in Rus’ lands. At the end of the summer of 1046, envoys of Hungarian lords, who had grown weary of the rule of Peter Orseolo (1038–1041, 1044–1046)—who had sunk to the status of a German vassal—arrived in Kiev and asked the sons of Vazul to regain the throne for the kindred of Saint Stephen.

After the princes crossed through the forests of the northeastern Carpathian ridges, András successfully overthrew Peter’s power and suppressed in blood the pagan restoration proclaimed by Vata, the lord of Békés castle, which, however, also cost Levente his life.

To consolidate the Christian kingdom as soon as possible, András called his younger brother, Duke Béla, home from abroad, pleading with him with these words: “For I have neither an heir nor a true brother except you. Be you my heir, and succeed me in the kingdom.” Béla heeded his brother’s call and returned home, and they divided the power: András, as king, ruled two-thirds of the country’s territory, while Béla, as duke, governed one-third of it.

Exercising royal prerogatives, the duke administered his territory with complete sovereignty: he had his own court, minted coins, made grants, and was considered the supreme warlord; only he was not permitted to conduct an independent foreign policy. Yet Béla supported his brother not only as a pillar and as the designated heir, but was essentially a co-ruler.

Their cooperation was harmonious for ten full years. However, in 1057—after nearly a decade of hostilities—András made peace with the German Empire, which, although the Hungarian ruler had successfully repelled two of its offensives (in 1051 and 1052), had until then kept his kingdom in a state of terror. The peace was to be sealed with a dynastic marriage: Princess Judith, the sister of Henry IV, the German king (1056–1105, emperor from 1084), married András’s son, Salamon. The German court insisted that Salamon should inherit András’s throne, and András, in the interest of the long-desired peace, accepted this condition: he had his son crowned during his own lifetime, thereby breaking his decade-old agreement with his brother.

The falling-out between the king and the duke is recounted in a truly uniquely depicted scene in the Hungarian chronicle tradition. András, paralyzed as a result of a stroke, was well aware that Béla held too much power and that the child Salamon could not rule without his consent. To secure his son’s throne, the aging ruler decided to put his brother to the test. At the end of 1059, he summoned Béla to Várkony castle, which rose on the right bank of the Tisza River, towering above the waters on the border between the king’s and the duke’s territories.

András planned to offer Béla a choice between the kingdom and the duchy. If he willingly renounced the throne and wished to support Salamon as duke, he would be allowed to leave in peace. However, if he dared to reach for the crown, he must perish. The aging king harbored no hopes, so he confided in two of his trusted men, who were to strike down the unsuspecting Béla.

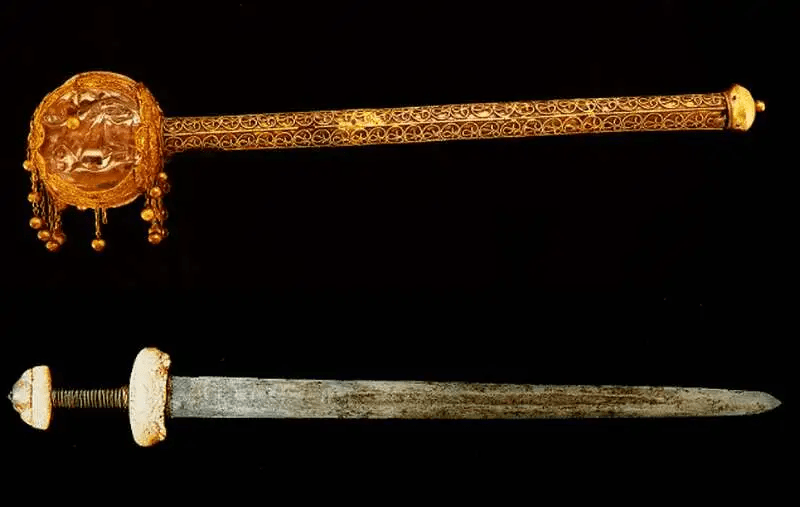

However, Nicholas (Miklós), the count of the heralds, who was guarding the palace door, overheard the conversation between András and his confidants. As he led Béla before the king, he whispered into the duke’s ear as he crossed the threshold: “If you wish to live, choose the sword.” When the duke entered the hall, he saw that beside his brother’s bed, on a red cloth, lay the crown and the sword. The ailing András sat up and spoke to his brother:

“Duke! I have crowned my son, not out of ambition, but for the sake of the peace of the realm, which I concluded with the emperor three days ago. But let your free will prevail: if you desire the kingdom, take the crown; if you desire the duchy, take the sword. Yield one of them to my son, yet the crown is yours by right.”

At that moment, Duke Béla understood the words of Count Miklós, and preserving his composure, he chose the sword, whereupon King András, with tears in his eyes and giving thanks, fell at his younger brother’s feet.

The root of the rift between the brothers was the still-unsettled succession system of the early Árpád era. After the death of Saint Stephen, the throne was occupied first by the foreign-born Peter Orseolo, then by Aba Sámuel (1041–1044), who was raised to power through election by the Hungarian elite.

András won back the throne for the kindred of the Turul. According to Györffy György, one of the most outstanding medievalists of the 20th century, András’s act of calling Béla home and making him duke was nothing less than the restoration of the principle of seniorate. András, who was still childless at the time, wished in this way to prevent the dynasty’s power from being shaken once again. However, after Salamon was born and his father had him crowned king during his own lifetime, the principle of primogeniture came into force, which inevitably led to a power struggle.

The power-sharing arrangement between the king and the duke was dual in nature. On one side of the coin, we see a division within the family, during which the brothers partitioned the family inheritance that had devolved upon them. Viewed from the other side, however, it cannot be regarded merely as a private affair of the dynasty, for those secular aristocrats who formed the retinue of the various male members of the ruling house capable of political action also had a stake in this division.

Their opportunities depended largely on how close to the fire—that is, to power—the royal scion they supported was, and what kind of relationship he had with authority. The Chronicle itself emphasizes, as one of the reasons for the souring of relations between the brothers, that certain opportunistic magnates incited them against each other. This dual nature of the conflict is clearly discernible in the legend, for the two brothers meet as two equal members of the family, yet they depart from the scene as ruler and vassal.

Regarding the dissolution of the pact between András and Béla, it is particularly interesting that the Hungarian chronicle tradition presents Béla’s behavior in two different ways across two scenes. In the section concerning Salamon’s coronation, we read about the duke’s indignation (Chapter 91), and then about how Béla and his sons, Géza (Géza I, 1074–1077) and Duke Ladislaus / László (St. Ladislaus I, 1077–1095), gave their consent to the anointing of the child (Chapter 92).

These two differing portrayals diverge precisely on the most important factor: the question of the consensus necessary for the election of a king. According to contemporary political thought, this consensus could be vetoed by the opposition of even a single person; however, the legality of unanimity was not diminished even if someone’s consent was extracted under threat of death, nor if it was given retroactively.

It is also extremely intriguing that the section concerning Béla’s consent and the scene at Várkony are found in the same chapter of the Hungarian Chronicle (Chapter 92). Seemingly, there is no contradiction, for when Béla chose the sword, he addressed his brother with these words: “Let the crown belong to your son, who has been anointed, and grant me the duchy.”

According to Gerics József, a leading scholar in the study of medieval political thought, behind the theatrical composition of the description of the Várkony meeting lies the sequence of events during which King András, by threatening Duke Béla with death, extorted his retrospective consent to the crowning of the child Salamon as king. However, according to Bagi Dániel, a professor at the University of Pécs, the scene involves no such extraction of consent. András’s goal was merely to persuade Béla to renounce his claim, thereby transforming the original legal relationship so that the duke would no longer simultaneously be the heir to the throne.

Historiographical research agrees that the Várkony scene is one of the oldest textual passages in the Hungarian chronicle tradition. However, regarding when the story was actually recorded, various hypotheses have emerged, two of which have gained particular prominence in the authoritative scholarly literature. According to Gerics, the first work of Hungarian historiography, the Ősgeszta (Ancient Gesta), was composed during the reign of Salamon (1063–1074), and based on the fact that the sword does not appear among the royal insignia in the Egbert-ordo liturgy used during Salamon’s coronation, he dated the writing of the story to this period.

According to Kristó Gyula, however, the Ősgeszta was created during the reign of Könyves Kálmán /Coloman the Learned (1095–1116), and the legend was also recorded at this time because it reflects certain principles of power-ideology that were particularly important for Kálmán (Coloman): by Béla renouncing his claim in favor of Solomon, who had already been crowned king, the doctrine of legitimacy can be discerned. Yet, by having Béla renounce under threat of death, it also preserves the claim to the throne for this branch of the family (Béla I was Kálmán’s grandfather).

What is certain is that the scene is retrospective, and as such, it presents the sequence of events from the perspective of the victorious party. The Várkony story paints an exceptionally strong picture of both its main characters: Andrew prepares to commit fratricide, while Béla, when he could assert his right to the throne, flees like a coward. Yet, a kind of sympathy awakens in the reader for the duke, for his decision is excused by the fact that his life was at stake, and his right to the crown is acknowledged even by the ruler who sought to take it from him. Since the text thus presents Béla as the moral victor, the story was probably committed to writing during the reign of his descendants.

However, the recording of the legendary story only became possible once it existed in a crystallized form; thus, the origin of the legend itself falls outside the framework of written tradition and is lost in the obscurity of orality. Following the renowned expert on old Hungarian literature, Kardos Tibor, the idea became established in scholarly consciousness that the tale of the Várkony meeting is an epic born of popular imagination, which depicted the political agreement between the king and the duke using the conventional methods of legend-formation, with the motif of choosing between good and evil at its core.

Szegfű László, a professor at the University of Szeged, expressed the opinion during his cultural-historical research that the Várkony scene, absorbed into the written tradition, could even have been the exposition of a larger-scale song, which found its way into the Chronicle through legendary channels. According to other conceptions, this choreographing of the brothers’ tragedy was written for the elite—as a discerning audience—to explain, through symbols that were obvious to them, namely the insignia of royal and ducal power, the process of how the original agreement between the king and the duke had dissolved, placing the grievances of Béla’s branch at the center of events.

King András’s attempt to secure his son’s throne by forcing the duke’s consent ultimately failed. Once it became clear to Béla that his life was in danger, he fled with his family to his former place of exile, the Polish court, only to later descend from the Carpathians at the head of Polish mercenaries and assert his right to the crown by force of arms.

He could also count on the support of the majority of the Hungarian lords, for by breaking his agreement with his brother and designating his son as heir at German insistence, András had been cast under the stifling shadow of pro-German sentiment. To quote Györffy: “It is the irony of fate that András, who fourteen years earlier had unseated Péter [Peter Orseolo]—who had fought with the help of German troops—now, having slipped into his predecessor’s role, was himself compelled to take up the fight against his own brother with German armies.” Béla defeated his brother; the paralyzed, aging András fell from his horse while fleeing, and his body was crushed by the galloping horses.

Béla had obtained his due, yet his reign could not be peaceful, for the young Hungarian kingdom once again had to reckon with a retaliatory strike from the German world power, whose clear aim became to place the anointed king, Salamon—who had married into the German ruling house—back on the Hungarian throne. Nor was family peace restored; the sons continued the struggle of their fathers.

After Béla’s death, Henry IV attacked the country and made Salamon king. However, after the German armies withdrew, Salamon was forced to agree with his uncles’ sons, Géza and László (Ladislaus). Thus, the institution of the duchy (ducatus) lived on, but the cooperation proved functional only temporarily. This division, which induced constant factional strife, was only eliminated by King Kálmán when he subjugated his brother, Duke Álmos, in 1106.

The original agreement between András and Béla served the purpose of ensuring that power would not slip from the hands of Árpád’s descendants again and that they would jointly secure the peace of the realm. However, this was not fulfilled completely, and as the Chronicle states, “this first division of the country was the very seed of discord and wars between the dukes and kings of Hungary.”

The first harvest of the sown seed was reaped by the brothers themselves, after changes in the political climate led to conflict. When Duke Béla rode out from within the walls of Várkony, the castle gate closed behind him—like the possibility of any further compromise or peaceful agreement—and it closed forever.

After ascending the throne following his victory, Béla proved to be an excellent king and partially fulfilled even his brother’s goals. The country’s economy truly flourished during his reign; the people’s standard of living increased considerably, and he also succeeded in strengthening Christianity.

From this period comes a passage from Kézai Simon’s writing in the Hungarian Chronicle, which also well illustrates the contemporary economic situation:

After him reigned Béla of the Benin [i.e., Béla I]. … He ordained all markets for buying and selling to be held on Saturday, and introduced Byzantine gold coins into circulation throughout his realm, which were to be exchanged for very small silver denarii, namely forty of them. Hence, to this day, forty denarii are called an ‘arany’ [gold piece], not because they are made of gold, but because forty denarii were once worth one Byzantine gold coin.”

Sources: Scriptores rerum Hungaricarum tempore ducum regumque stirpis Arpadianae gestarum I. Ed. Emericus Szentpétery. Bp. 1999.2 345., 351–357. Galambosi Péter https://ujkor.hu/content/a-varkonyi-egyezmeny-a-korona-es-kard-mondaja and https://www.eremkibocsato.hu/blog/138-a-korona-es-a-kard-legendaja

Dear Readers, I can only make this content available through small donations or by selling my books or T-shirts.

Please, support me with a coffee here: https://www.buymeacoffee.com/duhoxoxa

You can check out my books on Amazon or Draft2Digital. They are available in hardcover, paperback, or ebook:

https://www.amazon.com/dp/198020490X or at https://books2read.com/b/boYd81

My work can also be followed and supported on Patreon: Become a Patron!http://Become a Patron!

Become a Patron! Donations can be sent by PayPal, too: https://tinyurl.com/yknsvbk7

https://hungarianottomanwars.myspreadshop.com/all